Governments and financial institutions take painstaking efforts to consolidate banknotes, cheques, and passports with a variety of security features to protect them from counterfeiting. Yet every so often a counterfeiter emerges who can recreate these features and pass off fake documents as real ones. In response, institutions constantly develop newer and better components that are even harder to falsify.

Now, scientists from India have come up with an ink they say can make counterfeiters’ jobs harder.

Security printing

Counterfeiting is a serious threat to a range of enterprises. Spurious medicines packaged to look like the real thing can delay proper treatment or even kill. Branded consumer goods these days have tamper-resistant packaging to prevent cheats from selling low-quality replicas.

The printing of items with safeguards against counterfeiting is called security printing. It implements features that humans can detect by themselves or using simple tools. Examples include optically variable ink (whose colour appears to change when viewed from different angles), watermarks, holograms, and security threads. Features like raised shapes and shifting textures are security-printed features a person can check using the sense of touch.

Security printing can also incorporate more complex features that only machines can detect. Some modern passports include a small radio-frequency identification chip that only a scanner can read. Other examples include invisible barcodes, digital watermarks, and holograms.

A nanoparticle solution

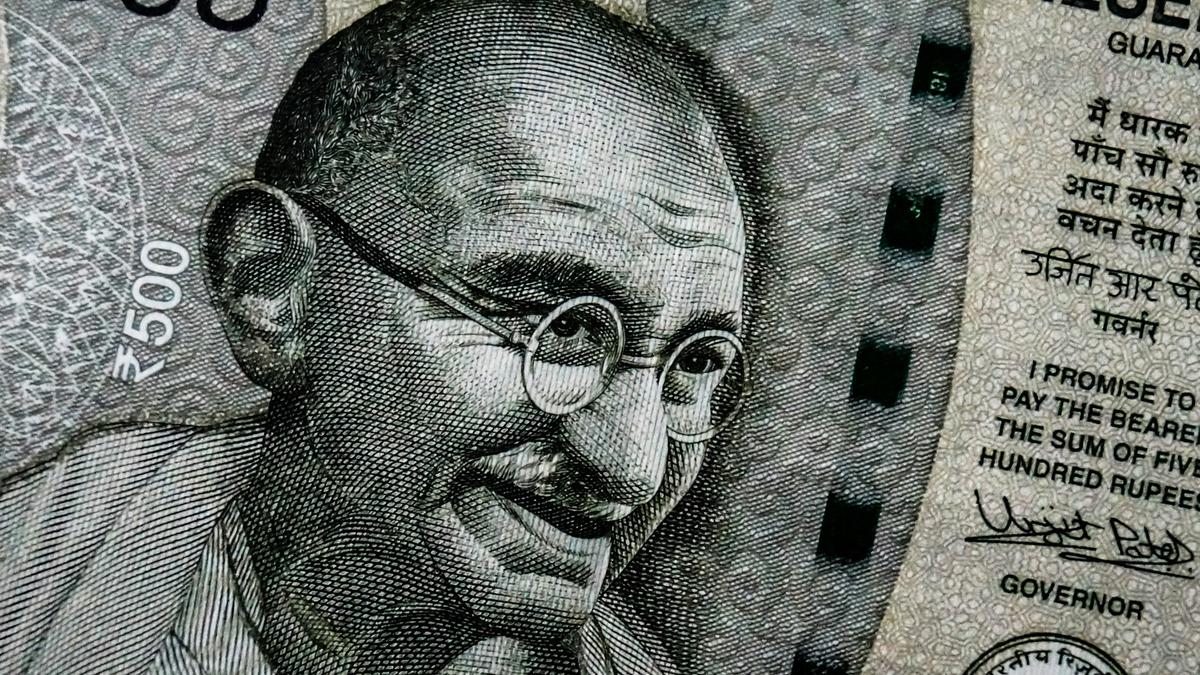

An important security-printed feature on Indian banknotes is a number panel in fluorescent ink located at the lower left corner. The numbers here are visible only in ultraviolet light.

Scientists from the Institute of Nano Science and Technology (INST), Mohali, and the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), Mumbai, have now reported a new ink they have made using nanoparticles. Nanoparticles are objects less than 100 nanometres (nm) wide. Because of their small size, they have properties that don’t appear in larger objects: they interact differently with light, respond differently to magnetic fields, and are chemically more reactive.

That the discovery of ways to manufacture semiconductor nanoparticles with unusual properties won three scientists the 2023 Nobel Prize for chemistry speaks to nanoparticles’ transformative effect on the world.

A simple recipe

In the new study, the nanoparticles were made of Sr2BiF7 (strontium bismuth fluoride) doped with lanthanide ions. Doping is the process of deliberately adding impurities to an existing crystal to give it properties it previously didn’t have.

Scientists used the coprecipitation technique to make the particles. “To do this, all the metal salts in the required quantity are dissolved in a suitable solvent. Once you get a clear solution, the required amount of precipitation agent is added while stirring,” INST scientist and study coauthor Sanyasinaidu Boddu said. Then they used a centrifuge to separate the deposited material out.

“The proposed compound is a new composition and is the first time we have synthesised it by a simple coprecipitation method at just above room temperature, which is very easy to scale up,” Boddu added.

The team then doped the Sr2BiF7 nanocrystals with ions of erbium and ytterbium, both lanthanide elements, and blended them with easily available polyvinyl chloride (PVC) ink. Finally, they used the screen printing technique to print some letters and numbers. Screen printing uses a stencil and a squeegee to transfer an image onto paper.

Two-light trick

When the researchers shone 365-nm wavelength ultraviolet light on these symbols, they emitted a cool blue glow. This process is called fluorescence: when an object absorbs light of one wavelength and emits light of a longer wavelength. Under 395-nm light, the letters glowed magenta. And when the researchers directed near infrared light of 980 nm at the letters, they fluoresced with an orange-red colour.

According to the team, currently available fluorescent inks are visible only under either ultraviolet light or infrared light but not both, adding that their ink stands out because it fluoresces in both the ultraviolet and the near-infrared parts of the spectrum. This, they contended in their paper, makes their ink more secure.

This low-cost ink also remains effective under varied brightness, temperature, and humidity conditions.

The study was published in ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces in September 2024.

Towards practical use

Bipin Kumar Gupta, senior principal scientist and professor at the CSIR National Physical Laboratory in New Delhi, who wasn’t involved in the study, said the paper didn’t report the quantum yield of the system. Quantum yield specifies how well the system converts incident light into fluorescence.

“Quantum yield is crucial for applications such as light emitting diodes and display devices. However, a very high quantum yield is not necessary for security applications. … From our report, it is very clear that the material is showing very good brightness under different excitation wavelengths, and that is sufficient for practical applications,” Boddu said.

Gupta received an Indian patent for a bi-luminescent security ink on January 30, 2025, after a US patent for the same object in February 2022. This ink is composed of gadolinium vanadate (GdVO4) doped with europium and emits red and green light under ultraviolet light of two wavelengths.

“To print security features on, say, currency notes, generally offset printing and not screen printing is used,” Gupta said when asked about the applicability of the ink developed at INST.

Offset printing uses a system of three rollers. One cylinder ‘offsets’ the image from a metal plate to a rubber blanket. The image is then transferred to the printing surface. Offset-printed images are sharper and capable of printing smaller letters.

“I agree that screen printing is not used for currency notes. However, there are many other places where you can use screen printing … We are [also] working towards offset printing.” Boddu said. “There are a few more steps to take this material to direct practical applications, and we are working on these steps.”

Unnati Ashar is a freelance science journalist.

Published – March 10, 2025 05:30 am IST