While religion is a sacred cow that doubles up as a cash cow, science is a cash cow that can often double up as a sacred cow in India. The popular belief is that a good dose of science in our educational system makes students intelligent, unprejudiced good citizens and inculcates objectivity and other “scientific qualities of mind” in them.

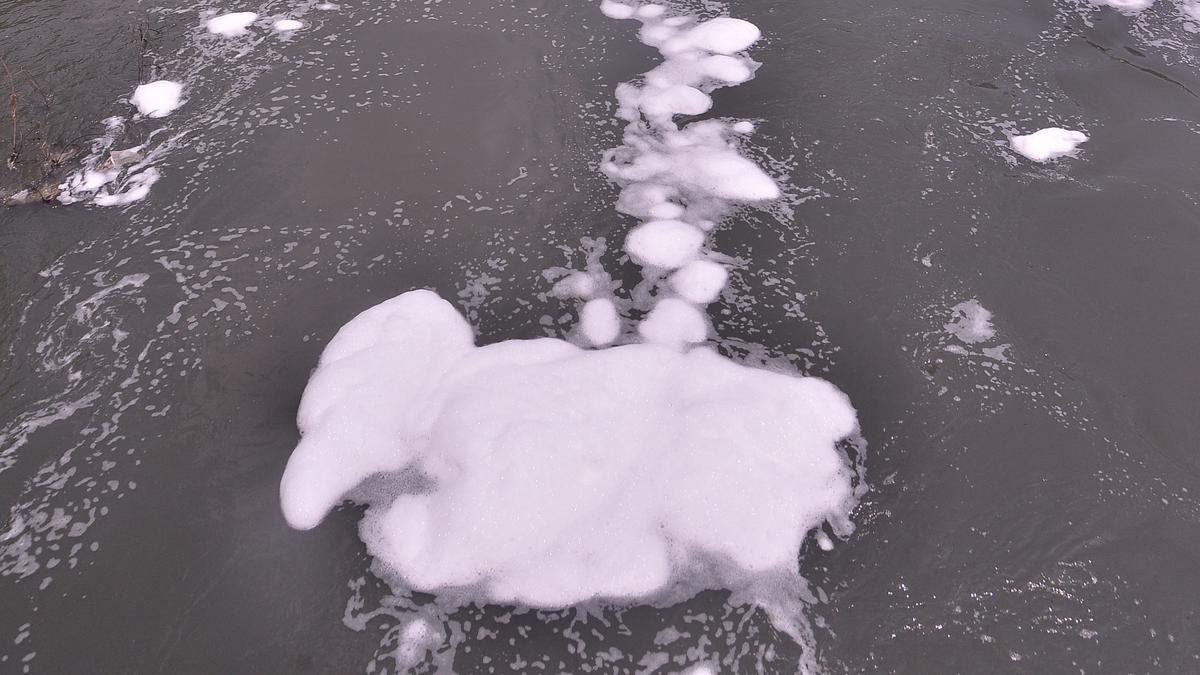

Yet, our institutions are flush with scientists with quarter-cooked scientific temper: power often has the upper hand over knowledge even within these scientific cantonments. The only knowledge that flows freely in our country is that from the barrel of the American journal. All other knowledge remains locked up as grey matter in our human resources. Information and knowledge want to be free, but any such ‘misadventure’ is instantly thwarted by the powers that be, brandishing a sengol in one hand and a sword in the other. A scholarly paper on the “giant gravity hole in the Indian Ocean” scores way above one dealing with the perennially recurring froth in Bellandur lake in Bengaluru. The frothing lake does not attract as many eyeballs as the ocean: the taste buds of the American journal are distinctly American.

Climb down the ivory tower

The travails of Bellandur, like the threats posed by developments such as artificial intelligence, should be forcing science to slow down its agenda based on a pursuit motivated by quick rewards and a misguided curiosity. The time has come for a large chunk of scientific forces to be re-deployed on the science-society border to scout for solutions to real-life problems. The new road is arduous and bumpy: while the space scientist can look up at the sky and continue romancing the moon, her earthly counterpart needs to climb down from the ivory tower where he has been ensconced tied to the ‘scientific method’, mingle with the crowd below, and get his hands dirty.

The majority of scientists trained in specific disciplines are content to solve puzzles by applying whichever theory is currently predominant in their discipline. A discipline acts like a lens: it filters out certain phenomena to be able to focus exclusively on others. Such scientists produce quantifiable results through simplified models and experiments that do not consider input from outside the sciences and overlook the social embeddedness of their activities.

The scientific method is based on beliefs in empiricism, replicability, and free exchange of information (so that others can test or attempt to replicate). It has predominantly followed the strategy of reductionism: an approach to understanding the whole of something by examining its parts (such as explaining heat in terms of the motion of molecules). But the reductionist approach cannot succeed in all cases. We can make sense of some things only by looking at them holistically. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts: the whole contains properties that cannot in principle be discovered through an analysis of its parts.

In the real world, it is often difficult to untangle a complicated web of causal relationships to determine which one is decisive. Relying only on individual disciplines to confront real-life problems provides a skewed perspective. If humans need to be served by science, science needs to be subservient to humans. Science then must confront the uncomfortable prospect of dealing with human complexities: diverse languages, vocabularies, world views, value systems, beliefs, faiths and cultures.

Many real-life problems call for practical knowledge generated to solve them long before there is enough research to establish an irrefutable point. The goal of achievement of truth or even full factual knowledge becomes a luxury. The boundary between subjectivity and objectivity becomes blurred. Ignorance, assumptions, value systems, uncertainty in fixing system boundaries and formulating problems, indeterminacy and differences in culture have all to be dealt with in the new regime. The carefully structured rule-based turf of normal science or faithful adherence to theoretical principles or agreed upon methodologies is of limited value in solving such complex problems. The natural sciences then need to work in tandem with human sciences.

The human sciences explain phenomena in terms of meanings and purposes rather than mechanical causes and effects. If you want to figure out what a group of people are up to, you cannot simply observe their physical movements; you must try to get ‘inside their heads’ and understand how they see the situation. The social sciences focus on behaviour: psychology seeks internal explanations while economics, sociology and political science seek explanations that are external to the individual.

Tap the humanities

The disciplines encompassed by the humanities — art and art history, history, literary studies, music and music education, philosophy, and religious studies — offer strategies for addressing dilemmas and acknowledging ambiguity and paradox. They provide tools for logical analysis and modes of discussing and debating moral and ethical questions.

Philosophy has interacted fruitfully with business and medicine on issues of ethics and reproductive technologies as well as with social scientists who are interested in rational choice theory. A wide variety of phenomena such as the debates on abortion and euthanasia, human cloning, stem cell research, terrorism and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have a religious component. The humanities are organised around the production of qualitative knowledge arrived at through sound argument rather than the empirical testing of theories. Other sources that facilitate addressing real-life problems include oral histories, eye-witness testimonies, artifacts, artistic creations, and forms of tacit knowledge.

A variety of perspectives and methods from different disciplines need to be brought to bear on a complex real-life problem. Connections need to be made between problems and disciplines, between problems and theories, and between problems and accumulated knowledge. All the relevant disciplines and their conflicting insights need to be identified, evaluated, and common ground created among them. An integrative model is then constructed that proposes a realistic solution to the problem. Science leaves this kind of integration of knowledge from other sources out of the “scientific method” altogether.

A traditional puzzle solver scientist is like the mediocre artist who starts with a clearly visualised picture in mind and ends up painting it without leaving any scope for growth and change during the process. The knowledge integration required to address complex real-life problems is, on the contrary, akin to that followed by a highly creative artist who starts painting with a general and often vague idea of what she wants to accomplish and discovers as she goes along what it is that she wants to do, using feedback from the developing work to suggest new approaches.

Questions to be asked

Are our scientists battle ready for this new role? Do our scientists possess the personality traits to work in collaboration with other disciplines? Will they recognise the ability of common citizens to become both critics and co-creators in knowledge production as part of an extended peer community? Will our scientists learn to live with and plan for contingencies: of managing complexity, uncertainty, and risk? Will they be able to think abstractly and dialectically?

Will our scientific institutions have linkages with external communities to foster multidirectional knowledge flows? Design incentives for sharing knowledge beyond publications? Will our scientists embrace all the elements of a proper scientific temper that must include humility and a yearning to learn lessons from the past and from other co-participants? Engage in cross-cultural conversation? Recognise different forms of knowledge — traditional, local, explicit, tacit? Adopt a humanistic approach to problem solving?

Are our scientists ready to let go of the sengol and the sword? Will they engage with other professionals and citizens and make a beginning by harnessing the diverse and dispersed forms of knowledge that are needed to address problems that impact their immediate neighbourhood and beyond? For Indian science and the public at large, that would be the best thing to happen since the invention of dal-roti.

Manu Rajan is an information scientist who retired recently from the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru