Last month, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin criticised the Union government for denying metro rail projects to Coimbatore and Madurai. This created some political controversy and also sparked a wave of urban aspiration. For many people, glitzy metros have become a sign of development and modernity. The absence of metros feels like a slight; their approval, a stamp of urban arrival.

But we need to step back and ask a crucial question: do cities like Madurai and Coimbatore actually need metro rail systems? Or has the metro become an elite-driven aspiration that is fundamentally misaligned with how Indian cities move and live?

Metro: not a mobility solution

India’s obsession with metros is relatively new but powerful. Over the past 15 years, metros have consumed nearly 40% of all urban development funds, becoming the single largest item in the urban budget. And yet, their contribution to mobility remains surprisingly limited. In most metro cities, only 5-12% of daily trips are made on the metro. The overwhelming majority of people still walk, cycle, or take buses and small para-transit modes.

This gap arises from the mismatch between metro systems and the pattern of everyday mobility in India. Nearly 90% of India’s urban workforce is informal, and the average daily commute for most workers is just 4-5 kilometres. These are short, dense journeys. They do not require high-speed, capital-intensive corridors designed for long-distance travel. Metros therefore do not serve the functional needs of the majority; they serve the elite imagination of a “world-class” city.

Tamil Nadu is one of India’s most urbanised States. The middle class is rapidly rising and so is an aspiring elite. With this comes a new visual language of development: gleaming airports, skywalks, elevated corridors and, invariably, metro lines. But elite desire is not a substitute for public need. Globally, cities comparable to Madurai or Coimbatore — medium-density, mixed-use, and compact — do not rely on metro systems. The successful examples are buses, surface-level rapid transit, cycling highways, pedestrian-first planning, and integrated feeder systems.

Singapore and Dubai, the frequently cited models, are not comparable in scale, governance, land control, or economic structure. Their metros work because their entire urban systems are shaped around them. Indian cities cannot simply copy-paste such models.

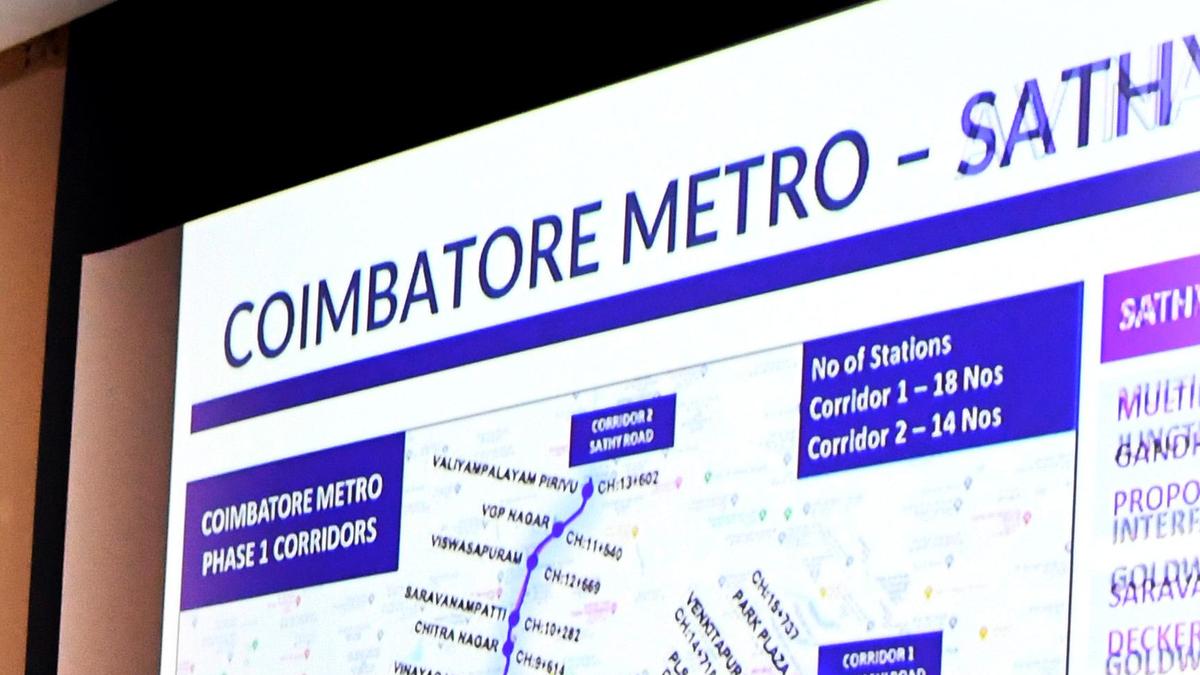

Metros are also extremely expensive. A metro costs ₹300 crore-900 crore per kilometre, depending on whether it is elevated or underground. Operating costs are equally steep. Almost no Indian metro recovers its costs through fares. Massive public subsidies keep them afloat. For cities like Coimbatore and Madurai, metro systems would mean decades of financial strain — diverting scarce funds away from schools, water supply, local roads, housing, public health, and basic neighbourhood infrastructure. To interpret the lack of metro allocation as a lack of development is to miss the real opportunity: freedom from a financially draining model.

Madurai’s radial street system and Coimbatore’s industrial neighbourhood clusters are inherently walkable and compact. The majority of workers move within short neighbourhood loops. Imposing metro systems onto such cities disrupts their organic form. What they need instead is a high-frequency electric buses, dedicated bus lanes on major corridors, shaded pedestrian networks, protected cycle tracks, better-integrated autos and share mobility, and neighbourhood-level last-mile systems. These are quick to build, cheaper, and beneficial.

Cities that redefined urban mobility in the last 30 years— Curitiba, Bogotá, Copenhagen, Freiburg, Medellín — did not rely on metros alone. Many, in fact, did not build metros at all. They invested in Bus Rapid Transit that moves more people per rupee than any metro; cycling superhighways; walkable neighbourhoods; hill connectivity via ropeways; multimodal integration rather than a single grand system. Modern mobility should not be defined by the scale of infrastructure, but by access, affordability, and last-mile connectivity and quality. India’s own mobility patterns mirror these best practices far more than the metro-dominated model.

Tamil Nadu’s opportunity

Mr. Stalin’s disappointment at being denied metro projects for Madurai and Coimbatore is understandable from a political point of view. But it also inadvertently gives Tamil Nadu a an opportunity to reimagine Coimbatore with a grid of fast, frequent electric buses, connected to industrial clusters; Madurai with pedestrian-first temple circuits, cycle highways, and seamlessly integrated shared autos; and cities where neighbourhoods are built as 15-minute communities, where work, school, healthcare, and markets lie within short walking or cycling distance. These constitute modern, climate-sensitive, affordable, and socially inclusive infrastructure. They match how people actually move. And most important, they won’t bankrupt cities.

Tamil Nadu must resist the pressure of equating development and modernity with metros. Instead, it should craft mobility systems that reflect the realities of its workers, the densities of its neighbourhoods, and the constraints of its municipal finances. If Tamil Nadu dares to think beyond the metro, it could set a new template for the rest of the country.

Tikender Singh Panwar is a former Deputy Mayor of Shimla and currently a member of the Kerala Urban Commission

Published – December 29, 2025 01:12 am IST