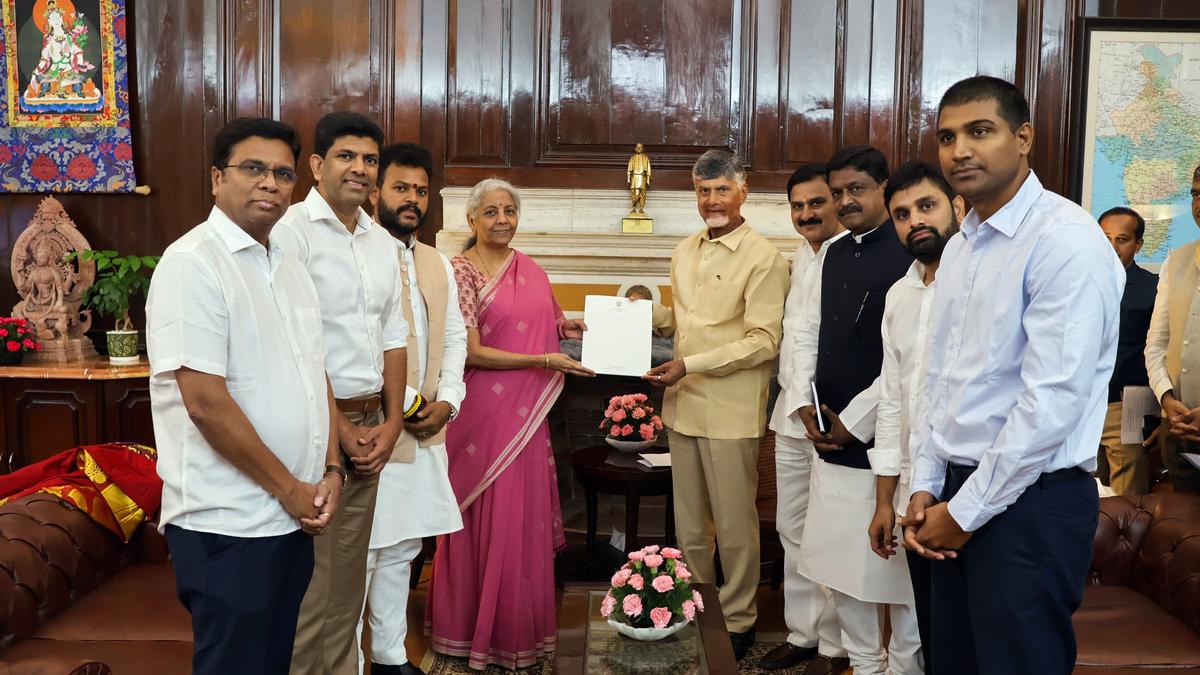

Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N. Chandrababu Naidu and other Ministers meet Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman in New Delhi.

| Photo Credit: ANI

Coalition politics is back at the Union level in a substantial way. The Bharatiya Janata Party is dependent on the Janata Dal (United) of Bihar and the Telugu Desam Party of Andhra Pradesh for its parliamentary majority. This is in contrast to 2014 and 2019, when de facto single-party governments came to office. With single-party majority becoming a thing of the past, demand for State-specific discretionary grants, or ‘special packages’, are back with a bang in public discussion.

The positive aspect of single-party dominance being tempered by the presence of coalition partners that can act as a check if unitary trends surge cannot be underestimated. Nevertheless, this is the time to test the hypothesis that when single-party dominance at the Union level fades, federal tendencies bloom and when a single-party majority under a strong leader at the Union level prevails, federal tendencies wilt.

If a healthy federal structure is to be nurtured, the fiscal boundaries, principles of assignment of taxes, and the basis for grants have to be transparent and objective. A federal setup can be asymmetric in a country that is characterised by linguistic, cultural, and economic diversity. But issues of asymmetry should be addressed by means of constitutional provisions that have both transparency and stability.

Also read|Currently, 11 States in India have Special Category Status.

The Constitution has provisions that address the issues of specific States, or States that have a special status with regard to certain matters mentioned in the Constitution. These provisions are covered, for instance, in Articles 371A to H (Article 370 for the erstwhile State of Jammu and Kashmir, of course, is abrogated).

Purely discretionary

On the contrary, special packages are purely discretionary. They may be need-based, but the need is not the proximate reason for granting a special package, which is an additional grant under Article 282, which falls under ‘Miscellaneous Financial Provisions’. More often than not, they are the result of the bargaining power of some State-level political parties that can tilt the scales of parliamentary majority. What does this augur for the health of our federal set-up?

That the outcome of an election can determine the fiscal distribution of national resources to a State or States goes against the grain of fiscal federalism (or, more correctly, of federal finance). Some States may be justified in their demands for funds, but allocation has to be through the mechanism of the Finance Commission. The Commission is constituted by the President every five years or earlier to make recommendations regarding the distribution of a share of taxes collected by the Union to the States, and how this is to be distributed among the States, as per Article 280; and disbursement of grants to States in need of assistance, as provided in Article 275. The 16th Finance Commission, which is already in existence, cannot be bypassed solely on account of partisan political exigencies.

When the same political party is in power at the Union and State levels, it is called a ‘double-engine sarkar. The main engine has lost the power to run on its own and the owners of smaller engines that are needed to pull the train along are making their own demands. While individual States may well need special packages, process is of the utmost importance. How have these events impacted the political and fiscal relations between the Union and the States?

Federal tendencies

The first issue here is the extent to which our polity is federal. The Constitution has been famously described as having a quasi-federal framework. C.H. Alexandrowicz, however, disputed this description in his work Constitutional Developments in India (1957), stating that in situations other than an Emergency, it assumes a federal character. The Supreme Court has made the succinct observation that our polity is amphibian — it can assume unitary and federal characters depending on whether or not there is an Emergency under Articles 352 and 356 in force (State of Rajasthan and Others v Union of India, 1977).

Be that as it may, it is often argued that the prevailing political environment crucially determines whether federal tendencies bloom or wilt. Keeping this proposition in mind, the hypothesis stated above can be put to test.

How fiscal distribution is done is cardinal in the test of whether or not federalism is strong. In the recent past, some States raised concerns about their share in the divisible pool of Union taxes facing a decline. Tax distribution is formula-based, and it is for the 16th Finance Commission to address this issue and undertake the delicate task of balancing the interests of the States inter se, and with those of the Centre.

The focus here is on grants, in the disbursement of which scope for discretion is wider. In our constitutional framework, the primary task of recommending grants to States in need of assistance is that of the Finance Commission, until Parliament makes legislation in this regard.

But the fact now is that the flow of discretionary grants to the States through Article 282 have far overtaken (by almost a factor of four) that of the grants recommended by the Finance Commissions. Acceding to demands for special packages which are raised by State-based parties, holding the key to parliamentary majority, will weaken the foundations of fiscal federalism, as it will result in diverting national resources away from other States, which too may have pressing needs. If this is allowed to happen, we will see the paradox of federal tendencies wilting instead of blooming when single-party dominance fades.

R. Mohan is a former Indian Revenue Service officer