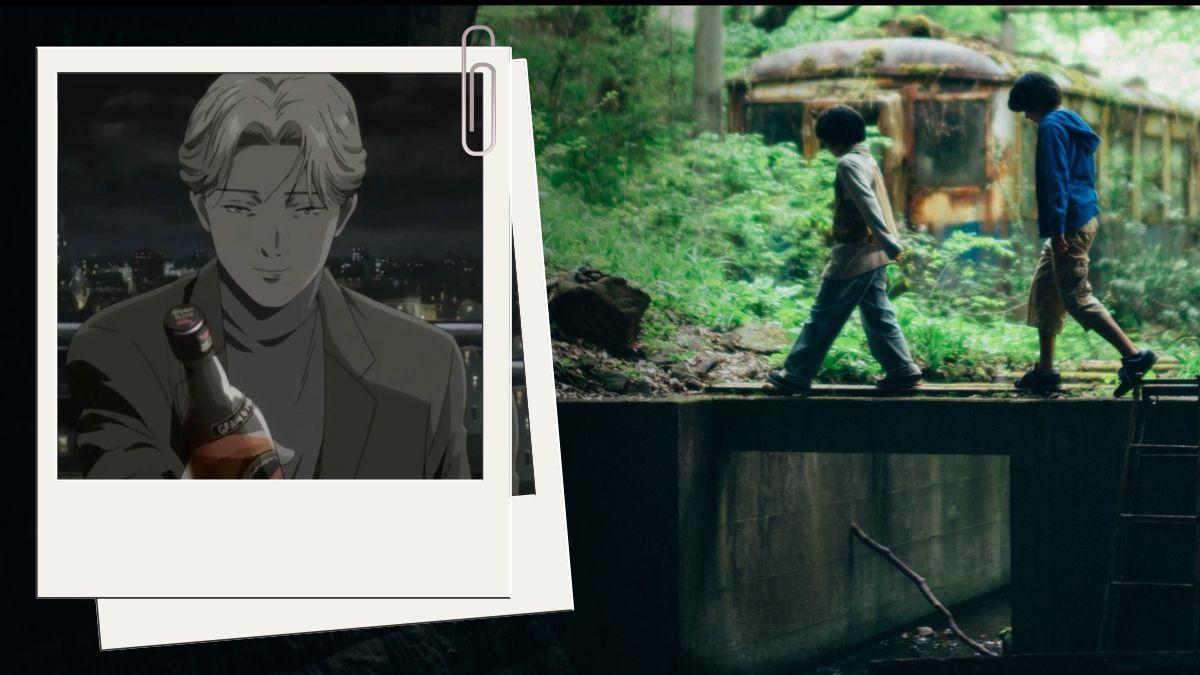

Stills from Noaki Urasawa and Hirokazu Kore-eda’s ‘Monster’

| Photo Credit: Netflix, MUBI

The curious poetry of two very different Japanese artists choosing the same word to crown their masterpieces (dare I say monsterpieces) was too tempting a combo to pass on. Monster, the anime (streaming on Netflix) looks outward, following a surgeon through the cold geometry of European institutions and ghosts of the past. The film, also called Monster, (available on MUBI) looks inward, threading through the intimacy of a Japanese city still learning how to talk about desire, guilt, and love without losing face. Together, they form a strange, loosely-connected diptych about blame, mythmaking, and the subtle violence that society deems commonplace.

From the drawing board

Veteran Japanese mangaka Naoki Urasawa’s seminal seinen manga is a long, unblinking stare into a bleak post-Cold War Europe. Madhouse Studio’s anime — a meticulous, 74-episode adaptation of his work — traces Dr Kenzo Tenma’s catastrophic act of goodness, saving the life of a boy who grows into an elegant, annihilating presence. The show slowly metastasises on dread, patience, and strained moralities, and the story keeps widening until Germany and much of Eastern Europe feels like one haunted organism, stitched together by guilt, secrecy, and bad decisions that ripple outward for decades.

What makes Monster extraordinary is its faith. It periodically trusts us to make sense or come to terms with its ethical conundrums without any sort of safety rail. Exiles, cops, loners, zealots and criminals — every side character carries secrets and trauma, each touched by Johan’s presence like a sickening stain that spreads relentlessly. Madhouse’s restrained grainy animation turns stillness into menace; Kuniaki Haishima’s unnerving score murmurs like a conscience trying to reason with itself. And Tenma’s long, unforgiving journey itself becomes an exhausting prayer. Can a man undo the kindness that doomed the world? Or is atonement only another myth we cling to so the universe feels negotiable?

A still from ‘Monster’

| Photo Credit:

Netflix

This isn’t a thriller sprinting toward revelation, but revelation as erosion itself. Institutions collapse. Stories collapse. Certainty collapses. All that remains is the simple idea that humans build monsters to explain their failures, and sometimes the explanation turns into one of the most terrifying serial killers in the history of fiction. If you enjoyed the moral vertigo of a soul unravelling in Breaking Bad, and if slow-burn paranoia excites you the way True Detective’s first season or Netflix’s incredible Mindhunter did, this is an essential viewing.

Foreign affairs

Japanese auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda’s most recent work shares the title and fascination with perception, yet it operates on a different emotional frequency. Where Urasawa dealt with continental guilt and seedy geopolitics woven into character tragedy, Kore-eda chooses intimacy, everyday politeness, and a dangerously elastic narrative. The film’s Roshomon effect rewinds and reframes the same events through a mother, a teacher, and finally the children at the story’s centre. Each turn redraws and remaps the moralities of perception.

Kore-eda’s filmmaking remains tender, observant, and uncompromising. The children carry shame, tenderness, terror, and fragile hope in their small bodies. Schools, press, parental pride, rumour and taboo — all these institutions contribute to a fog where harm multiplies while everyone performs good intent. The final movement — buoyed by the late Ryuichi Sakamoto’s poignant music — feels like a tentative resurrection. Not triumphant, not even clean. Simply human, and therefore precious.

A still from ‘Monster’

| Photo Credit:

MUBI

Kore-eda’s own Shoplifters is an obvious companion piece — another portrait of fragile bonds surviving the weight of social judgment. Fellow Queer Palm nominee, Lukas Dhont’s devastating Close, is similarly haunted by the things adults refuse to see. And for stories about shame and the violent etiquette of conformity, Lee Chang-dong’s Burning lingers in the same unsettling ambiguity. If any of these works resonated with you, you’ll probably respond to how Monster studies its foggy moralities through tenderness.

Ctrl+Alt+Cinema is a fortnightly column that brings you handpicked gems from the boundless offerings of world cinema and anime.

Published – December 26, 2025 07:37 pm IST