In the ongoing public discourse on the convulsions in the AIADMK, many wonder why party general secretary Edappadi K. Palaniswami should not follow the example set by his predecessor Jayalalithaa and the organisation’s founder M.G. Ramachandran in taking back those who were once critical of them.

In this context, references are being made to former Ministers S.D. Somasundaram (SDS) and K. Kalimuthu, who were re-accommodated by MGR and Jayalalithaa, respectively, after a period of separation triggered by bitter criticism.

Similarly, if one were to take a look at the DMK’s history, there have been many instances of the party’s former president M. Karunanidhi taking back several prominent personalities, including Sathiavani Muthu and Nanjil K. Manoharan, into the organisation after condoning them for all that they had done against him politically.

SDS’ spat with MGR, Jayalalithaa

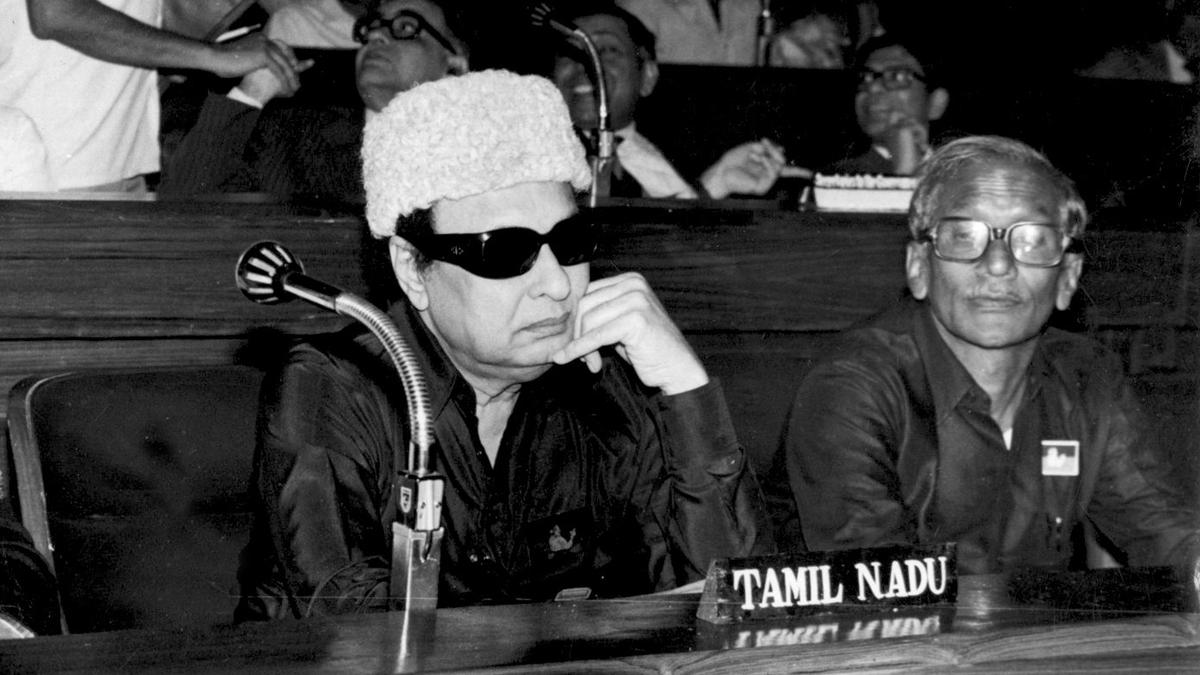

SDS was one of those who came out of the DMK when MGR formed the AIADMK in 1972. He would often say: “I have been with him through thick and thin and working for the growth of the AIADMK.” After being Revenue Minister in MGR’s Cabinet for six years at a stretch, SDS developed differences of opinion with the Chief Minister around July 1984 over a couple of matters, such as the entrance test for admissions to professional colleges and the issues of Sri Lankan Tamils.

S.D. Somasundaram in 1984

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

While expressing his views on these issues, he had been “brutally blunt,” The Hindu reported on July 10, 1984. It was then that his portfolio was changed from Revenue to Food. When asked about these differences at a press conference in Tiruchi, he retorted: “Why should I resign or quit the party?” SDS called himself a “strict disciplinarian,” discharging his work as a Minister with all “sincerity and integrity.”

At the same time, some of the district units of the AIADMK organised black-flag demonstrations against him and passed resolutions to boycott him. He was one of the bitter critics of Jayalalithaa (then spelt Jayalalitha), who was the party’s propaganda secretary and a Member of Parliament (Rajya Sabha). At one stage, he had accused her of being “de facto Chief Minister.” He had trained his guns on MGR, alleging nothing concrete had been done to root out corruption and remove “bootleggers and looters” from the party though it was more than two months since the Chief Minister swore to do so, this newspaper reported on August 28, 1984.

He also came down on then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, with whom MGR had re-established ties, for the toppling of the National Conference regime in Jammu and Kashmir and the dismissal of the N.T. Rama Rao ministry in Andhra Pradesh, which occurred in a matter of a month. When the AIADMK’s executive met in Chennai on September 1, SDS predictably stayed away, and the party’s decision-making body had recommended his removal. Three legislators had followed him after his removal from the Cabinet and the party. His reaction to his dismissal was: “l am happy to be out of the Cabinet headed by a corrupt Chief Minister.”

Later, he floated a party — Namadhu Kazhagam. At the time of the 1984 Lok Sabha and Assembly polls in the State, he initially attempted to strike an electoral deal with the DMK, but Karunanidhi was unmoved. This forced him to go at it alone, and his nominees were fielded in 150 Assembly constituencies and 15 Lok Sabha constituencies. The party’s performance was disastrous. He suffered a humiliating defeat in his home constituency, Pattukkottai, at the hands of a less-known AIADMK candidate and forfeited the deposit.

Jayalalithaa and S.D. Somasundaram

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

After a period of lull in his political activity, SDS, in April 1986, took out a procession to Raj Bhavan and presented a memorandum to Governor S.L. Khurana, seeking the constitution of an enquiry commission by the Union government against the AIADMK regime to go into his 30 allegations of corruption relating to Excise, Commercial Taxes, Forests, Transport, and Cooperation departments. It was then that MGR’s health was failing and he visited the United States at periodical intervals for check-ups.

In November that year, SDS surprised everyone when he called on the Chief Minister at his Ramavaram residence and returned to the AIADMK a few days later. Ironically, he later became a key member of the Jayalalithaa camp in the party and contested unsuccessfully from Thiruverambur in 1989 as the candidate of the AIADMK (Jayalalithaa). He once again became the Revenue Minister in 1991 and held the portfolio for five years, before turning against Jayalalithaa again.

Kalimuthu vs Jayalalithaa

Kalimuthu, like SDS, could not reconcile himself to the rise of Jayalalithaa in the Dravidian major in the second half of the 1980s. He was one of her well-known baiters, along with former Minister R.M. Veerappan. In 1985, when MGR made Jayalalithaa the propaganda secretary again after a brief break, and there were rumours that she might even be inducted into the Cabinet, Kalimuthu, who was Minister in the MGR Cabinet during 1977-86, had openly conveyed his reservations. According to a report on India Today (November 30, 1985): “Kalimuthu has been collecting MLAs’ signatures on a statement opposing Jayalalitha’s possible induction into the Cabinet and listing her so-called misdeeds during MGR’s convalescence in New York early this year.”

K. Kalimuthu. File

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

At the time of the split in the AIADMK after M.G.R.’s death, he was naturally with the Janaki Ramachandran faction. In the January 1989 Assembly poll, he finished fourth in Theni, not being able to retain his deposit. When the two factions came together subsequently, he was one of those opposing the merger and set up a party called AIADMK (MGR). However, in May, he chose to work under Jayalalithaa, who had nominated him for the Sivakasi Lok Sabha constituency during the general elections later that year. Though he left the AIADMK about a year later, he returned and in 2001, he was made Speaker of the Assembly.

Sathiavani Muthu’s rebellion

In the DMK, in 1974, when Chief Minister Karunanidhi appeared to have consolidated his position after MGR’s departure from the party in October 1972, then Harijan Welfare (which was how the subject of Adi-Dravidar and Tribal Welfare was called in the 1970s) Minister Sathiavani Muthu revolted against him. She had stunned everyone by levelling, on the floor of the Assembly, charges against officials for being non-cooperative in carrying out welfare measures for Scheduled Castes. She had also alleged that funds, meant for the development of SCs, were used for promoting the welfare of Backward Classes. The Chief Minister had initially sought to iron out the differences with her by seeking the details from her and assuring the public of action against erring officials. But she repeated her criticism and in May that year, she was dropped from the Cabinet. Muthu went on to float a party before merging it with the AIADMK. She even authored a publication strongly critical of Karunanidhi.

Muthu was elected to the Rajya Sabha and when MGR, in 1979, expressed support to the breakaway faction of the Janata led by Charan Singh for staking claim to power at the Centre, he chose her and A. Bala Pajanor to be his party’s representatives as Cabinet Ministers in the short-lived regime. Muthu’s attempt to enter the Assembly after a gap of eight years during the 1984 Assembly poll was not successful as she lost in Perambur. She was with Janaki Ramachandran at the time of the party’s split before returning to the DMK in 1989.

Sathiavani Muthu

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

Najil Manoharan’s exit and re-entry

Four years later, it was the turn of Najil K. Manoharan, who was Finance Minister in the MGR’s first Cabinet (1977-80) and returned to the DMK subsequently, to express his views against Karunanidhi. In the second half of June 1993, Manoharan, who was then deputy general secretary of the DMK, published a poem in a pro-DMK Tamil daily which was considered, within the ranks of the Dravidian major, “indecent and vile” and aimed at the party leadership. The daily had subsequently carried another poem, which was indirectly critical of Manoharan, who had later denied he had insulted Karunanidhi. He did not mean the DMK chief in the poem. He and Mr. Karunanidhi had mutual love and affection and their friendship was “more than five decades old,” The Hindu reported on June 25, 1993.

However, the party leadership felt “enough is enough” and decided to sack him. The trigger for Manoharan’s poem was apparently his non-inclusion in the board of trustees of the DMK Trust. Yet, within a few days, Manoharan expressed regret and submitted a letter, seeking re-admission to the party.

Nanjil K. Manoharan

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

The party was also in the midst of uneasiness between Karunanidhi and Vaiko (then known V. Gopalsamy), one of the leading MPs of the party then. It was stated that Manoharan’s “U-turn” was due to his failure to rope in many district secretaries as also Mr. Vaiko to challenge the leadership on the expulsion issue. When Mr. Vaiko was spearheading a revolt against Karunanidhi five months later, Manoharan was taken back into the party. He had accused then Chief Minister Jayalalithaa of being behind Mr. Vaiko’s resistance against the DMK president, this newspaper reported on December 5, 1993. In May 1996, Manoharan was included in the Cabinet led by Karunanidhi and, four years later, he died in harness.

A seasoned member of the AIADMK, who knows the history of the two Dravidian parties, however, contends that in the case of his party now, the groups headed by former leaders, O. Panneerselvam, V.K. Sasikala, and T.T.V. Dhinakaran, do not seem to be positively inclined to work under the leadership of Mr. Palaniswami, making the reunion virtually impossible. Yet, a long-standing member of the AIADMK, who is now with Mr. Panneerselvam, says his group’s leader has expressed readiness to join hands with the parent body unconditionally. It appears key leaders of the AIADMK, both past and present, are yet to appreciate the significance of lessons of the past.