On December 30, astronomer Jonathan McDowell posted on X.com: “The abandoned Chandrayaan-3 propulsion module, left in a 125000 x 305000 km orbit in 2024, had a bit of a tussle with the Moon in November and has now been found in a 365000 x 983000 km x 22 deg orbit”.

Dr. McDowell is well-known for, among other things, publishing Jonathan’s Space Report, “an irregular newsletter which attempts to provide a detailed and pedantic historical record of the space age” and for maintaining the ‘General Catalog of Artificial Space Objects’.

Tug of war

His post describes a common problem in spaceflight: once you leave a spacecraft in a very large and lopsided orbit around the earth that comes anywhere near the moon’s path, the moon’s gravity can keep nudging it in ways that are hard to predict far in advance.

“Moon-orbit-crossing” in his post means the object’s orbit around the earth reaches out to distances comparable to the moon’s distance. As a result at some points the object and the moon can pass relatively close to each other. When that happens, the moon’s gravity matters a lot.

In low-earth orbit, i.e. 150-2,000 km above sea level, the earth’s gravity dominates and the motion of satellites here is fairly regular. But when you get closer to the moon, you’re effectively in a three-body situation: the earth pulls, the moon pulls, and an object in between that’s affected by both their pulls moves quickly through regions where the balance of those pulls changes.

In these systems, small differences in timing or position can lead to big differences later. That is what Dr. McDowell meant by “chaotic”. The orbit is still governed by the laws of physics but the underlying equations are very difficult to solve.

This was also the premise of the science fiction book and later Netflix show ‘3 Body Problem’. An alien species inhabited a world in a system with three suns orbiting each other, repeatedly leading to periods of climate chaos. The three-body problem asks how three masses move when each attracts the others by gravity. In classical mechanics, this problem doesn’t have a general closed-form solution, meaning there’s no single formula with which you can predict how the system will evolve for all possible starting positions, speeds, and masses.

A looping path

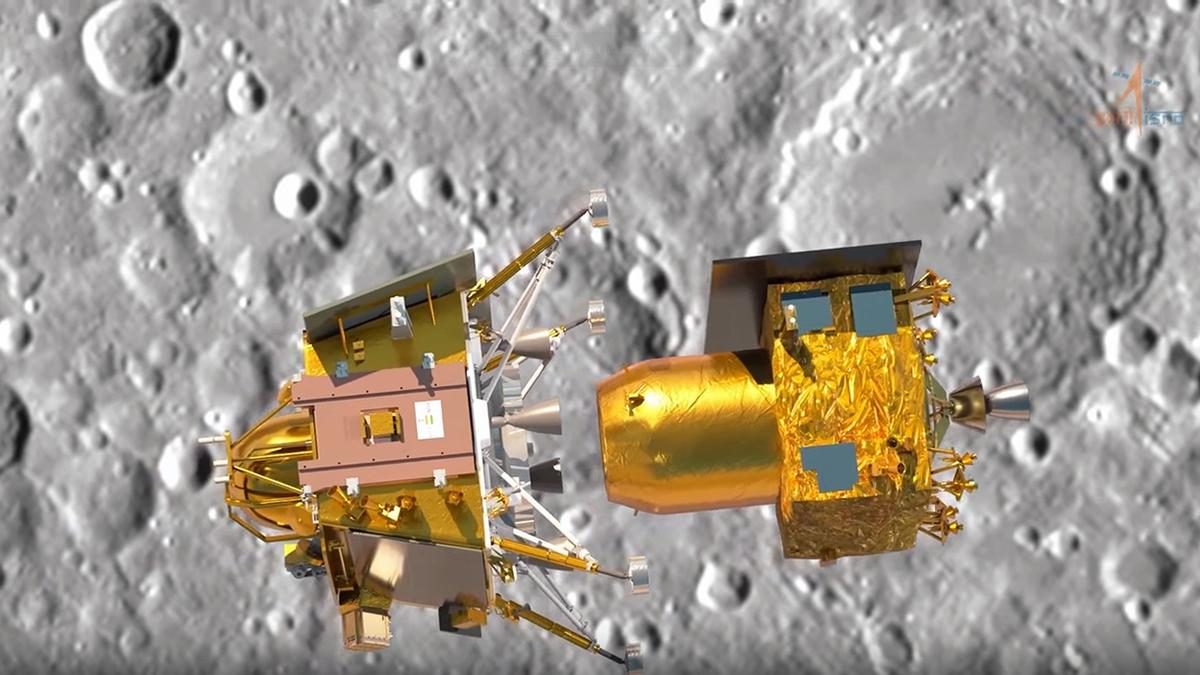

The Chandrayaan-2 mission ended in partial failure when its lunar lander crashed on the moon’s surface in 2019. But since it had successfully launched an orbital module, which continued to orbit the moon, the Chandrayaan-3 mission only consisted of a propulsion module, a lander, and a rover.

After the lander and rover descended on the moon in August 2023, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) moved the propulsion module to a 125,000 x 305,000 km orbit around the earth in October. These two numbers are the distances from the earth at the closest point (perigee) and farthest point (apogee) of the orbit.

So the propulsion module was looping around the earth on a highly elliptical path: it came as close as about 125,000 km, then swung out to about 305,000 km, approaching the moon’s average distance (~384,000 km). That means it spent some of its time in the moon’s gravitational neighbourhood.

The moon’s kick

When Dr. McDowell says it had “a tussle with the moon in November”, he means the propulsion module had a relatively close pass by the moon. During a close pass, the moon’s gravity can kick, or suddenly change, the object’s speed and direction relative to the earth. This is not like friction or a collision but a purely gravitational interaction. Depending on the geometry, the kick can raise the orbit, lower it, tilt it or change its shape.

According to an ISRO statement in November, the propulsion module entered the moon’s “sphere of influence” on November 4 and exited it on November 14. The organisation said it tracked the ‘event’ using the Indian Deep Space Network (IDSN), a collection of antennae near Bengaluru that, together with data received by similar ground stations operated by NASA and other space agencies, monitors Indian assets in space.

While it was in the moon’s sphere of influence, the propulsion module flew by the moon twice: on November 6 it came within 3,740 km of the lunar surface and on November 11 within 4,537 km.

After this encounter, the orbit of the propulsion module changed in three ways. First, it became much larger overall. According to ISRO the apogee jumped to 727,000 km; Dr. McDowell wrote in his post on December 30 that it was 983,000 km high. Either number is well beyond the moon’s distance and a sign that the moon’s pull added (or rearranged) orbital energy in the earth’s frame.

Second, the new orbit has a different shape and orientation. ISRO concluded the perigee to be 409,000 km and Dr. McDowell, 365,000 km. That is, the propulsion module no longer comes back anywhere near 125,000 km; it stays high almost all the time. And third, the orbit became noticeably tilted, by 22º, relative to the earth’s equator. This happened because the moon’s gravity pulled the module in a direction that wasn’t perfectly aligned with its current motion and orbital plane. As a result the module’s angular momentum vector changed.

Very different orbit

Per the statement, ISRO took “special care … to monitor its trajectory” and its proximity to other space objects. “The overall satellite performance was normal during the flyby and no close approach was experienced with the other lunar orbiters. This event garnered valuable insights and experience from mission planning, operations, flight dynamics perspectives, and especially enhanced the understanding of disturbance torque effects.”

In sum, ISRO left the Chandrayaan-3 propulsion module in a wide earth orbit that grazed the moon’s neighbourhood. In November 2025, the timing lined up such that the moon passed close enough to strongly tug on the propulsion module. This reshaped its orbit, pushing it into a higher, more tilted, and more extreme ellipse. As a result, tracking teams now found it with a very different set of orbital parameters.

In his post, Dr. McDowell credited amateur astronomer Sam Deen, astronomer Luca Buzzi, and Bill Gray, who developed notable software to track near-earth objects, “for figuring out that the suspected asteroid CE1M9G2 … was actually Chandrayaan-3”.

Published – December 30, 2025 08:37 am IST