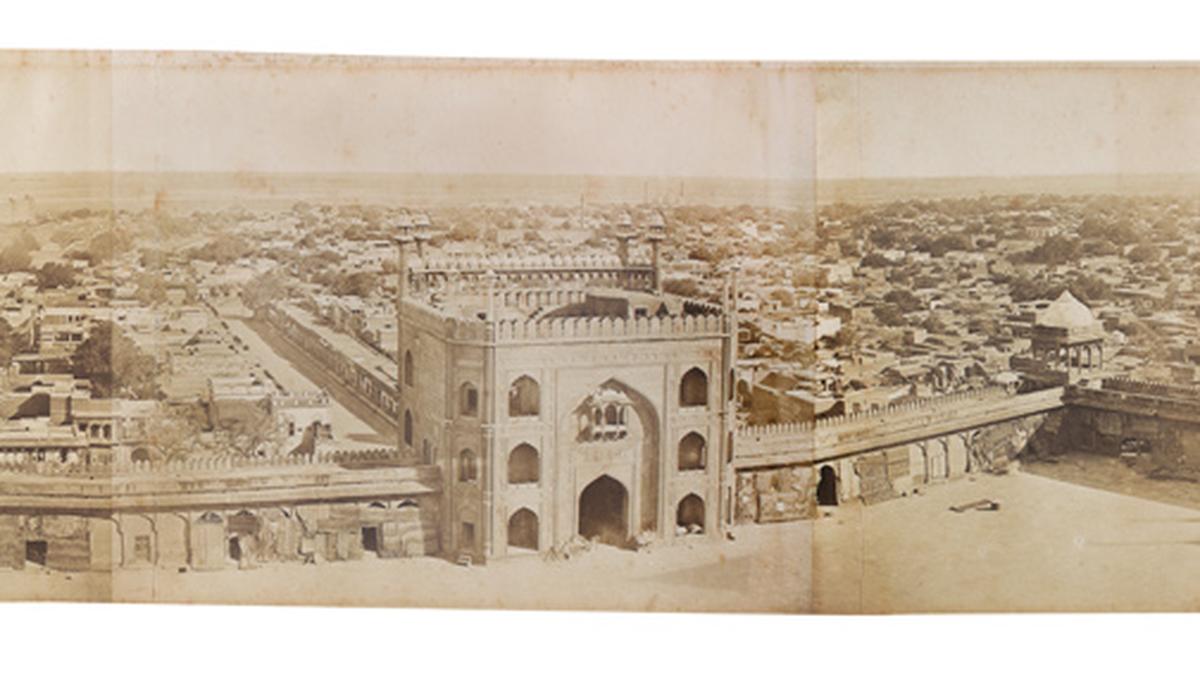

Panoramic view of Delhi from Jumma Masjid (Jama Masjid), 1858

| Photo Credit: Felice Beato

Photographer Felice Beato’s Panoramic View of Delhi from Jumma Masjid presents the old city behind a gossamer curtain of dust. In this 1858 sepia-tint picture the viewer can see the vast courtyard of ‘the mosque commanding a view of the world’. Beyond it, is a rabbit’s warren of streets, dotted with clumps of trees. The rooftops of Delhi bake in the sun, and layer upon layer of the old Mughal city unveils itself beyond the great brass door — the water troughs for washing, pigeons in flight, and the bastions of the Red Fort glowering from afar.

This silver albumen print from a glass negative is part of DAG’s Histories in the Making, an exhibition that explores Indian monuments through photography between 1855 and 1920. It turns the spotlight away from the crowded tourist hubs that they have become, and a restless populace that now inhabits them, to linger on these symbols that once conveyed a glorious and languid pace of life.

Sanchi Stupa, 1880

| Photo Credit:

Lala Deen Dayal

The exhibition showcases more than 150 objects drawn from DAG’s holdings created through photographic technology such as paper and glass negatives; collotype, albumen, and silver gelatin prints; stereographs, postcards, carte-de-visite and cabinet cards. It is accompanied by a catalogue edited by Sudeshna Guha, former curatorial manager and research associate of the photographic collections at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge.

Caves of Elephanta, 1855-1862

| Photo Credit:

William Johnson and William Henderson

Guha, who has written on the photographs of ancient monuments amassed by Sir John Marshall, Director-General of ASI appointed by Lord Curzon, says, “The photographic archive of DAG is rather vast and expectantly conveys the story of the early archaeological and anthropological surveys of India, and of major technological feats, such as the railways. There is a colonial gaze in the photographs taken by British officers and military men who worked for the East India Company, and this met some of the administrative demands of the Raj for a photographic record.”

“However, the Indian photographers emulated and built upon the aesthetics of the European photographers, and therefore it is not possible to distinguish between the foreign and native gaze. The exhibition shows particularly two — Lala Deen Dayal and Narayan Vinayak Virkar — who worked upon the picturesque imagery brought to photography prominently by Samuel Bourne, to create a high market value for their photographs,” she adds.

View of the Sacred Tank in the Great Pagoda (Minakshi Sundareshvara Temple, Madurai), 1858

| Photo Credit:

Linnaeus Tripe

Photographers made their way across a variegated subcontinent, capturing its ethos through architectural views and landscapes. Guha writes, “Photography was launched in 1839 with announcements by Louis Daguerre and William Talbot of their inventions of the Daguerreotype and Talbotype in France and Britain respectively. Photography came to India within months of the announcement of the daguerreotype. By 1847, the scholarship on Indian history was streamlined into two distinct modes of field enquiry – archaeological and architectural because of two pioneering protagonists, Alexander Cunningham and James Fergusson. Cunningham explored Sarnath and the North, while Fergusson explored the South, central and western India.”

Part of the Pillar of Kootub (Qutb Minar, Delhi), 1858

| Photo Credit:

Felice Beato

A parade of photographers such as Edmund Lyon who photographed the pillars of the famed temple at Rameswaram (1867-68); Eugene Impey who clicked the Kootub complex rising from the surrounding shrubbery with its stunning calligraphy visible even from a distance in 1858; the picturesque Dal Canal by Samuel Bourne and James Craddock in 1860 leaping out of the pages like a still-life; Babu Jageshwar Prasad’s Munikarnika Ghat shot in the 1880s, filled with corniches and bamboo parasols, the dead and the dying; the great water palace of Deeg rising from the waters of Bharatpur like a ghostly sentinel by Raja Deen Dayal; and Felice Beato who documented the Mutiny when it was almost over in Delhi, Agra, Lucknow and Kanpur with a “clear focus on British travails and victories” rack up story after story on the Raj in India.

The photographs, where monuments take centrestage, present India’s past in elegant picturesque prose, its epic cycles of affluence and ruin captured in sepia. Guha says that John Forbes Watson, director of the Indian Museum, London, noted that there was great public regard for the photographs of Indian architecture in Britain and Europe and went on to showcase many of them at the International Exposition in Paris in 1867. Amateur photographic societies that sprung up across India also did their bit to document these monuments.

Exterior of Zenana, Agra, 1905

| Photo Credit:

Raphael Tuck & Sons

Another collectible during that period was postcards of the monuments; the first illustrated postcards to be published from India in 1896 were apparently by the German photographer W Roessler in Calcutta, who had them printed in Austria. Omar Khan, collector and writer on early postcards in South Asia, says eloquently in the catalogue, “For the British, the dispatch of an archaeology postcard of India was the pluck of an imperial string. No firm better illustrated India’s past than Raphael Tuck & Sons. They sold oilettes, made to resemble oil paintings and successfully marketed them by hosting annual collector competitions in which the winners, who had amassed thousands of Tuck cards, were awarded grand prizes.”

Hooseinabad Gateway, Lucknow, 1905

| Photo Credit:

Raphael Tuck & Sons

Most were British women who had never left the shores of ol’ Blighty but wished to vicariously participate in the sights and sounds of the Empire.

Histories in the Making is on show till October 19 at DAG, New Delhi.

Published – October 10, 2024 11:11 am IST