The Indian passport is meant to be issued only to Indian citizens. Only citizens are supposed to be on the electoral rolls of the country. But holding an Indian passport or having one’s name on the electoral rolls is no proof of citizenship, because people can, and have, forged their way to these documents. This is a conflict between evidence of status and status of evidence. This vexed question of citizenship governance has resurfaced in the context of Election Commission of India’s countrywide Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls.

The legal challenge against the SIR is based on the following grounds. First, the ECI has no power to determine citizenship, and only the Home Ministry has. Second, there is no provision in the law for an en masse SIR and it can only be done selectively. Third, whether one is a foreigner can be determined only by the Union Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) under the Citizenship Act and by quasi-judicial bodies such as Foreigners Tribunals constituted under the Foreigners Act, 1946. The ECI has argued that its constitutional mandate to determine the eligibility of individuals to be included in the electoral rolls necessarily entails verifying their citizenship status. Its central contention is that the process of assessing eligibility for enrolment cannot be equated with a formal determination of citizenship. While these arguments may or may not be accepted by the Supreme Court of India (which is hearing the case), the issues at hand are more fundamental, political and even philosophical in nature. What is being questioned in the SIR is the presumption that all residents are citizens unless proven otherwise.

For the individual to prove

Countrywide, there is no single piece of evidence that proves Indian citizenship — a document that has the status of being evidence of citizenship status. A legal regime for a countrywide adjudication of everyone’s citizenship passed by Parliament is awaiting rollout. In Parliament in August, the Centre was asked what proof there is of Indian citizenship. The Centre — the Minister of Home to be precise — said: “The Citizenship Act, 1955, as amended in 2004, provides the Central Government to compulsorily register every citizen of India and issue a National Identity Card to him.

The procedure for the same has been laid down in the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003.” The rules state that national identity cards are to be issued to citizens whose particulars are entered in the National Register of Citizens (NRC), a subset of the National Population Register (NPR), which lists all residents. The NRC is mandated in the Act; the NPR is authorised by rules framed under the Act. The NRC is to include only citizens who have proved that they indeed are.

The law is clear that when challenged, the onus of proving citizenship lies is on the individual, and not the state. Alongside the 2010 Census during the United Progressive Alliance government, data for the NPR was collected, which was updated in 2015, with details of 119 crore residents. Whether the NPR will be updated along with Census 2027 remains unclear. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) dropped its promise of an NRC from the 2024 election manifesto. Any resident can be on the NPR, but to graduate to the NRC, one has to prove that they meet the requirements under the Citizenship Act.

Editorial | Burden of proof: On SIR 2.0 and the voter

The founders of the Republic favoured a territorial conception of citizenship, Jus Soli or ‘Right of the Soil’, though elements of blood lineage and ethnicity were also included in the original citizenship Act. Jus Sanguinis or ‘Right of Blood/lineage’ gained more prominence over the decades. Consequently, citizenship by birth in India has multiple caveats. As the law stands today, to be eligible for citizenship by birth in India, regardless of who the parents are, one has to be born before July 1, 1987. Persons born in India between July 1, 1987 and December 2, 2004 are citizens of India only if either of the parents is a citizen of the country at the time of his/her birth; and for persons born in India on or after December 3, 2004 to be eligible for citizenship, apart from at least one parent being a citizen, the other parent must not be an ‘illegal migrant’ at the time of birth. The Citizenship Act of 1955 has been amended multiple times, and it was in 2003 that legislation determined that a section of the residents are ‘illegal immigrants’ who were to be identified and deported; they and their progeny would not be eligible for Indian citizenship by birth. For a person to be eligible for Indian citizenship by birth now, either both their parents must be determined as citizens, or one of them should be a citizen and the other should not be an illegal immigrant. A section of the identified illegal immigrants qualify for Indian citizenship under the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, which turned controversial for the explicit religious test that it mandates.

In 2008, in a pilot project, a few lakh Indians were issued the Multipurpose National Identity Card (MNIC) by the Union Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA). The card, with an embedded electronic chip with 10 fingerprints, an iris scan, and photograph, along with name, date of birth, parents’ names, place of birth, and place of issue had 10-year validity. The NRC for the whole country was a promise made in the BJP’s 2019 manifesto. In 2024, the party went silent on it and we do not hear much about it. The SIR by the ECI comes as a proxy of this exercise.

A persisting conflict

Regardless of which Ministry or Department oversees the exercise, questions of citizenship, treason and sedition with regard to an individual are decided at the lowest level of bureaucracy and the police. The state’s authority is created by the will of the people. People are sovereign; the state is their creation and it is not supposed to be the other way around.

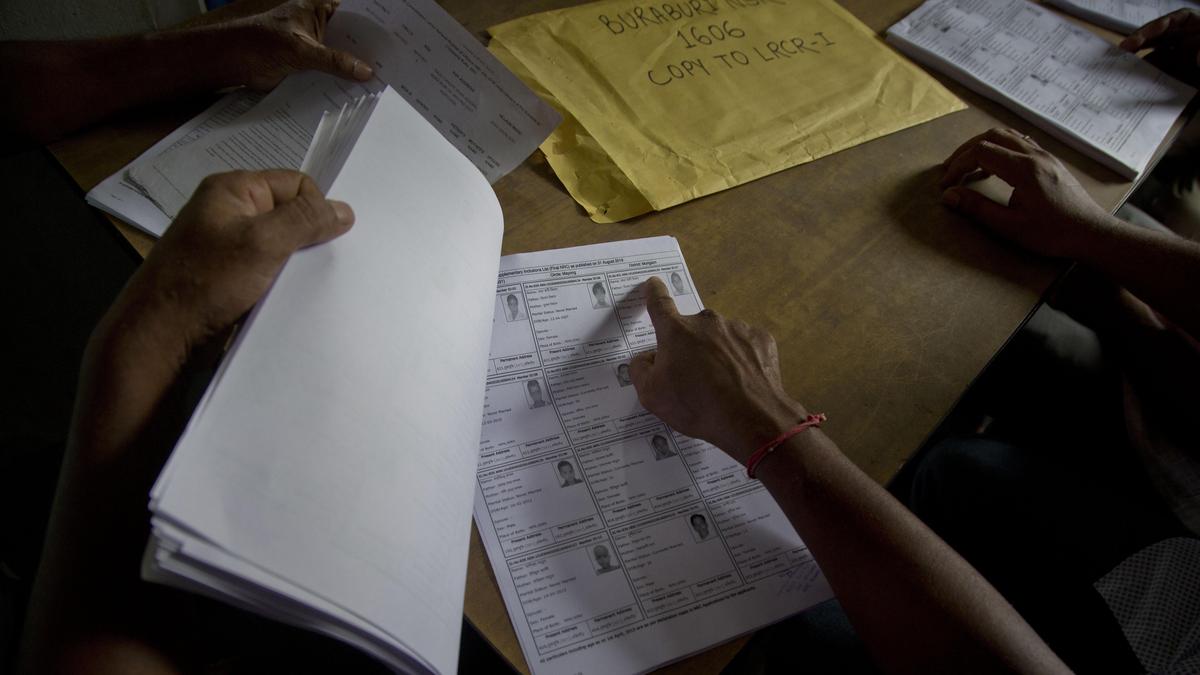

Therefore, the modern state apparatus which has been invested with the authority to determine who constitute the people has contradiction built in it. Whether an individual is a citizen, and whether they are not treasonous or seditious are all determined on a daily basis by the border agent, the constable, the village clerk and whoever is enlisting the voter.

This conflict persists whether or not the ECI is stopped from carrying out the SIR. The same primary schoolteacher who works for the SIR under ECI supervision would make the same determination for NPR, and then the NRC under the MHA’s oversight, if things come to that. The definition, design and application of citizenship laws are such that the state decides who the people are.

The Assam exercise

The only State that has a draft NRC — Assam — is proof of this concept. To implement the Assam Accord, Parliament passed the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 1985, which, inserted Section 6A into the Citizenship Act, 1955, effectively creating a separate citizenship regime for Assam that was different from the rest of India, and creating three different cut-offs for residents, and placing them under various citizenship status. A draft NRC was published in 2019, and it marked 19 lakh residents out of 3.29 crore as D, for Doubtful citizenship. A person whose status as a citizen could not be “ascertained beyond reasonable doubt … to the satisfaction of the registering authority”, as per the rules as applied in Assam, ends up as a doubtful citizen.

The BJP government in Assam rejected the draft because a large number of people marked D were Hindus. Once a person is marked D in the NRC and/or the electoral rolls, their voting rights can be suspended, their citizenship can be determined by a foreigner’s tribunal, and they could be deported. The process relied heavily on legacy records, of possessing documents regarding parentage and residency that go back several decades, to prove the varying cut-off dates of their residency and lineage.

There can be no argument that nobody should determine the citizenship of a resident of India or voting right is delinked from citizenship status. There can be a debate on who should be making that determination, and about the fairness and transparency of the process. Discomforting as it is, the burden is on the individual to establish the eligibility for citizenship. And it is the administrative state that makes the determination of who constitutes people. That is a fundamental paradox of democracy and in the relationship between the people and the state.

Published – December 09, 2025 12:16 am IST