The regime change in Bangladesh following the 2024 uprising not only unsettled its domestic political landscape but also triggered strategic recalibrations across its neighbourhood. For India, the implications are profound. The two countries share not just contiguous territories, common resources, transboundary rivers, and adjacent maritime zones, but also people bound by a shared inheritance of history, language, culture, and practices. This organic interdependence has long been harnessed through amicable bilateral partnerships, most notably during India’s engagement with Bangladesh’s former Awami League administration in the past decade. Their relationship was marked not only by an expanding portfolio of cooperation but also by the ability to navigate long-standing contentious issues without derailing the overall goodwill. Over the past decade, this partnership fostered a sense of near-permanent amicability and created a strong foundation for India’s foreign policy aspirations.

However, the popular uprising in Bangladesh in August 2024, the ousting of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, her subsequent shelter in India, and the establishment of an interim government in Dhaka brought this strategic continuity to a sudden halt. Since then, India–Bangladesh relations have witnessed a visible cooling, with implications across multiple sectors of cooperation. Among these, connectivity — a cornerstone of bilateral engagement — has borne the brunt of diplomatic uncertainty. As a foundational sector that enables trade, mobility, people-to-people exchanges, and regional integration, connectivity tends to be the most vulnerable to political tensions. In the current climate, despite undeniable geographic interdependencies, the future of India–Bangladesh connectivity hangs in the balance.

As bilateral goodwill retreats, it becomes critical to analyse the factors that previously compelled both nations to enhance connectivity, and to assess how the current political shifts in Dhaka are now disrupting established frameworks, stalling ongoing initiatives, and injecting strategic hesitations into what was once considered a model of subregional cooperation.

History of partition and reality of geography

When the Indian subcontinent was partitioned, Bangladesh (erstwhile East Pakistan) was carved out of its eastern territories, leaving India’s Northeast landlocked. Before partition, trade and commerce of India’s Northeast with the rest of the country used to pass through the territories of what is now Bangladesh. Even after partition, rail and river transit across the erstwhile East Pakistan continued until March 1965, when, as a consequence of the India-Pakistan War, all transit traffic was suspended.

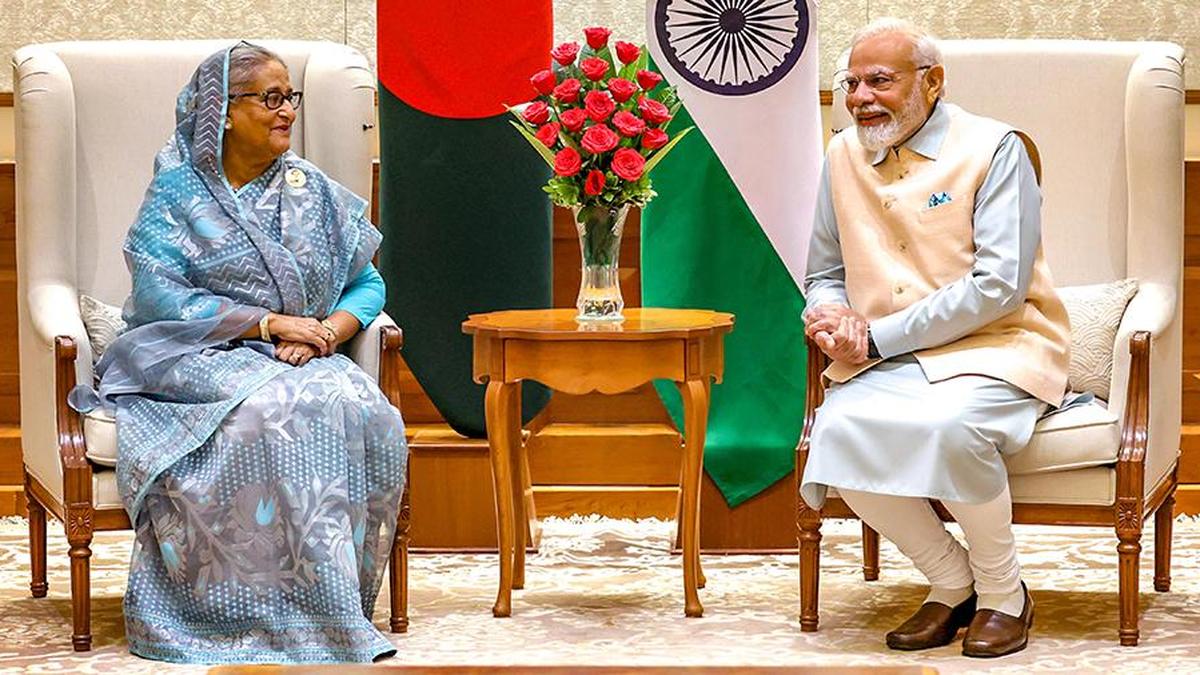

Political differences between the Governments of India and Pakistan overrode the age-old interdependencies, and it was only after East Pakistan became Bangladesh, under a government favourably disposed towards India, that river transit was restored in 1972. Therefore, although geographical proximity creates geopolitical necessities for cooperation among countries, promoting good bilateral ties is ultimately a diplomatic choice and is primarily driven by an alignment of priorities between the governments in consideration. This strategic alignment between India and Bangladesh was most evident in the past decade, in the partnership between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, shaped primarily by four key factors.

Resolution of existing disputes between India and Bangladesh: Although India had played a crucial role in securing Bangladesh’s independence in 1971, the two countries continued to face disputes regarding their maritime and land boundaries. Eventually, the maritime boundary dispute was resolved in 2014 by the Permanent Court of Arbitration, and in the following year, 2015, the land boundary was settled through a bilateral agreement. The resolution of these long-standing issues left a clean slate for the two governments to cooperate on shared concerns and opportunities.

China’s growing presence in the region: India was acutely aware of China’s growing presence in the Indian Ocean Region, especially in its neighbouring countries and oceans, which New Delhi considered to be its primary area of interest. Beijing had already established a strong foothold in Bangladesh through its investments across multiple sectors, including trade, infrastructure development, and defence. India, therefore, realised the need to strengthen its ties with its neighbouring countries to retain its prominence in the region. For Bangladesh, although China offered major infrastructure investment and economic leverage, it also brought risks. Overreliance on China could create long-term debt dependency, and deeper military ties could complicate Bangladesh’s traditionally neutral posture. India provided the perfect alternative to balance this over-dependence.

Political Legacy: Sheikh Hasina had inherited her father, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s, legacy of a favourable disposition towards India, which stemmed from India’s crucial role in Bangladesh’s Liberation War of 1971. Thereafter, Ms. Hasina had taken shelter in India for six years after her father’s assassination in 1975. With her at the helm, the Awami League naturally sought closer ties with New Delhi, especially as it marked a departure from the Bangladesh Nationalist Party government’s overt lean towards Pakistan.

Capitalising interdependence: These factors collectively fostered a strong policy convergence between India and Bangladesh. The alignment was further reinforced by India’s strategic compulsions — particularly its troubled western front with Pakistan — and the foreign policy priorities of the newly elected Indian government in 2014. Following the collapse of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Summit in 2016, New Delhi intensified its focus on its eastern neighbourhood. Under the frameworks of the ‘Act East’ and ‘Neighbourhood First’ policies, Bangladesh emerged as India’s most pivotal eastern partner. Stronger ties with Dhaka bore the promise of improved connectivity for the landlocked Northeast, granting easy access to the Bay of Bengal, which would increase its opportunities for maritime commerce and economic prosperity.

India and Bangladesh share a border of 4,096 km, of which 1,880 km runs along the Northeastern States of Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram. India’s Northeast is connected with the rest of the country by a 22-km-wide stretch of land called the Chicken’s Neck, which passes through a hilly terrain with steep roads and multiple hairpin bends. Due to unique geographic positioning, Bangladesh often provides the shortest route for transport between India’s Northeast and the rest of the country. For example, Agartala, the capital of Tripura, is 1,650 km from Kolkata via Shillong and Guwahati, whereas the distance between Agartala and Kolkata via Bangladesh is just about 350 km. Moreover, the distance between important cities of Bangladesh and Northeast India ranges between 20-200 km. A well-connected and fast-developing Northeast would not only boost India’s domestic development but also aid its foreign policy outreach to its other eastern neighbours, namely Nepal, Bhutan and Myanmar. Strong ties with Bangladesh would also help ensure better cooperation in managing conventional and non-conventional security threats. For example, one of Ms. Hasina’s earliest moves was to eliminate anti-India insurgent groups who had found a haven in Bangladesh.

Better connectivity with New Delhi offered Bangladesh a gateway to broader economic growth as the latter is nearly enclosed by Indian territory, often described as ‘India locked’. Subsequently, India emerged as Bangladesh’s second-largest trading partner. India’s investments in Bangladesh’s developmental infrastructure helped the Muslim-majority country improve its economy, and the use of India’s logistical facilities aided Dhaka’s export-driven economy, especially the ready-made garment (RMG) industry.

Under Ms. Hasina, Bangladesh sought to play a more prominent role in regional forums, such as the “Bay of Bengal Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation” (BIMSTEC), aligning with India’s initiatives for sub-regional connectivity and integration. Due to these factors, the inherent interdependence between India and Bangladesh, which had previously been overlooked due to political differences, was leveraged for mutual progress. Consequently, foremost among the areas of cooperation between the two countries was connectivity.

Retracing historical conduits and constructing new channels

Accordingly, over the decade-long partnership between the two countries (from 2014 – until the middle of 2024), a period that came to be known as the “Golden Chapter” or the Shonali Odhyay in India-Bangladesh ties, multiple connectivity initiatives were undertaken and enhanced to capitalise on the interdependencies and reap mutual rewards.

Rail links: Among the latest developments, in 2022, the Mitali Express began operations, running bi-weekly from New Jalpaiguri in northern West Bengal to Dhaka, Bangladesh. This express serves as the third passenger train after the Bandhan Express, running twice a week between Khulna and Kolkata, and the Maitree Express, operating five times a week between Dhaka and Kolkata. These train services provide an affordable and reliable means of transportation between India and Bangladesh, boosting bilateral trade and the tourism industry. The Mitali Express, particularly, provided access for Bangladeshi tourists to favoured Indian destinations such as Darjeeling, Dooars, and Sikkim. In 2023, the Akhaura-Agartala cross-border rail link was launched to reduce the travelling time and distance between India’s Northeast and Kolkata, bypassing the Siliguri Corridor. The track is in place, and freight trials took place in September 2023; however, customs facilities, platforms, and access roads remain unfinished. In February 2025, freight train services between India and Bangladesh resumed after being suspended for about nine months, but passenger services remain stalled indefinitely.

Roadways: India and Bangladesh are connected through multiple road links. Recent among them is the Maitri Setu — a 1.9 km long bridge over the Feni River, joining Sabroom, the southernmost point of Tripura, India, with Ramgarh in Bangladesh. While the Maitri Setu was inaugurated in 2021, the land port at Sabroom was nearing completion in June 2024. Passenger transport was scheduled to start along this route in September 2024, followed by the movement of goods. This would facilitate people’s movement from Cox’s Bazaar or the Chittagong Hill Tracts to Tripura, and aid the transport of goods from Tripura to the Chattogram Port, which lies at a distance of only 80 km from Sabroom. If functional, the Maitri Setu would have created a passage for trade between India’s Northeast and Southeast Asia. Connected with the Akhaura-Agartala rail link, the Maitri Setu would offer multi-modal connectivity to other parts of Bangladesh as well. Its operations, however, remain stalled.

Inland waterways: As road and railway projects are costly and carry environmental impacts, the governments of both countries explored the viable option of utilising the maze of inland waterways connecting the Northeast with Bangladesh to ferry cargo and passengers. Some of the old riverine routes between India and Bangladesh have already been reactivated. Under the India-Bangladesh Protocol on Inland Water Transit and Trade (PIWTT) — first signed in 1972, and last renewed in 2025 with a clause for automatic renewal every five years — the two countries ferry goods using specified waterways passing through both territories. The second Addendum to the PIWTT, signed on May 20, 2020, added five new ports of call and two extended ports of call on both the Indian and Bangladesh sides.

Connectivity through seaports: Post-partition, although India continued to use the Chattogram Port, its access was terminated during the 1965 Indo-Pakistan War. Since then, it has been keen to regain substantial access to the port as it is logistically more convenient to access from the Northeast compared to the Kolkata Port, which can only be reached via the Siliguri Corridor. For Bangladesh, allowing India access to the Chattogram and Mongla ports via established multimodal channels not only meant more business but also paved the way for transit cargo to reach these ports from landlocked Nepal and Bhutan.

In 2015, India and Bangladesh signed the Agreement on Coastal Shipping, enabling direct regular shipping between ports on India’s east coast and Bangladesh, particularly Chattogram. However, this agreement is limited to the movement of India’s domestic cargo between the Northeast and the rest of India via Chattogram. It can be expanded to facilitate the movement of third-country export-import cargo, especially from and to India’s Northeast. In April 2022, Ms. Hasina offered greater use of the Chattogram Port to India. Currently, India uses the transit and transhipment facilities of the Chattogram Port for the Northeast’s trade. In Mongla, India is financing the upgradation of Mongla Port via a concessional Line of Credit. India secured the operating rights to a terminal in Mongla port in June 2024. It also funded the construction of the Khulna-Mongla Port rail link, connecting the port to the rail network in Khulna. This project aimed to reduce logistical hurdles and cargo transportation costs between West Bengal and the Northeast . However, services have yet to begin on this route.

Connectivity initiatives demand complementarities in governance. However, the regime change in Bangladesh last year and India’s strained ties with the new interim government have had a directly detrimental impact on these connectivity projects. Trade, too, has dwindled.

Impact of the regime change on India-Bangladesh connectivity

The mass uprising in Bangladesh in August 2024, which led to Sheikh Hasina seeking refuge in India and the formation of an interim government in Dhaka, halted the ongoing connectivity projects and the overarching bilateral cooperation. As the year-old interim administration grapples with economic and political instability, its foreign policy reveals a degree of ambivalence toward India amid its ongoing quest for domestic legitimacy. The legal validity of the interim government has been repeatedly questioned due to a 2011 Constitutional Amendment Act that abolished the system of non-party caretaker governments in Bangladesh. Although the High Court Division of the Bangladesh Supreme Court had recently ‘partially annulled the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution and reinstated the non-partisan, neutral caretaker government system’, legalising the Yunus administration, it remains a non-elected government in a country struggling to revive democracy. The regime’s primary source of popular support is the Anti-discrimination Student Movement, which nominated it to power.

Nationwide student protests that led to the ouster of the former Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina, from Bangladesh had a distinct anti-India chord, due to New Delhi’s support for the Awami League administration. Accordingly, upon coming to power, the interim government led by Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus has been distancing itself from the Awami League’s legacy and affiliations in its search for popular support. Reflecting the same approach in its foreign policy, a distance has also crept into India-Bangladesh relations, with several issues such as Ms. Hasina’s pending extradition from India and numerous reports of attacks on Hindu minorities in Bangladesh deepening the rift. The new interim government’s repeated attempts to pin blame on India for its domestic chaos and its marked attempts to strengthen ties with Pakistan and China without consideration of India’s strategic sensitivities have further significantly undermined the once-flourishing bilateral relationship between the two neighbours.

Thus, trade between India and Bangladesh has reportedly declined since the regime change, with border closures, issues with customs clearances, and increased security surveillance hindering the smooth flow of goods between the two countries. Between April and October 2023, India’s exports to Bangladesh fell by 13.3% and imports dipped by 2.3%. Fly ash exports via the Indo-Bangladesh protocol route through Kolkata port also dropped by 15%-25% during the peak construction season. The bustling Benapole-Petrapole land ports at the India-Bangladesh border, responsible for nearly 30% of bilateral trade, now witness significantly less traffic. The reduced activity has severely impacted border-dependent livelihoods. People-to-people connectivity has also been impaired with the three railway services suspended since July 2024. Bus services and other public transport remain unavailable, and private vehicles have been charging exorbitant rates to cross the land border.

Under such circumstances, New Delhi is recalibrating its connectivity dependence on Bangladesh through diplomatic means.

Showcasing the Northeast’s geographic strength

In late March 2025, Mr. Yunus made a controversial statement on India’s Northeast during his first state visit to Beijing. Addressing the Chinese President Xi Jinping, he remarked, “The seven States of eastern India, known as the Seven Sisters, are a landlocked region. They have no direct access to the ocean. We are the only guardians of the ocean for this entire region. This opens up a huge opportunity. It could become an extension of the Chinese economy — build things, produce things, market things, bring goods to China and export them to the rest of the world.” Mr. Yunus’s statement reflected a disregard for India’s strategic sensitivities. It also showed a lack of understanding about Bangladesh’s geopolitical reality.

While India’s landlocked Northeast can certainly benefit from a more convenient access to the Bay of Bengal via Bangladesh’s ports, it can still access the sea via the Kolkata Port in West Bengal. Indeed, India has the longest coastline in the Bay of Bengal and also owns the operational rights to the Sittwe Port on the Myanmar coastline. Consequently, the assertion that Dhaka is the “Guardian of the Ocean” overstated Bangladesh’s role. It overlooked the broader regional maritime geography, which is a collaborative space for all the Bay littoral countries. Moreover, Bangladesh itself relies on India’s Northeast for its transit trade to Nepal and Bhutan. New Delhi subsequently revoked the transhipment facility that allowed Bangladesh to export goods to third countries via Indian land customs stations, ports, and airports.

Interestingly, although Mr. Yunus’s remark portrayed India’s Northeast as a region of strategic vulnerability, New Delhi did not revoke Dhaka’s transit trade rights through this territory. This has two diplomatic motivations; first, to make the interim government realise the Northeast’s value, as a critical hinterland and transit territory for Bangladesh’s own third country trade, especially in light of the terminated transhipment facilities; and second to showcase India’s commitment towards its bilateral ties with Nepal and Bhutan, and the development of the Bay of Bengal region, at a time when its bilateral ties are strained with Bay littorals- Bangladesh and Myanmar. Cancelling transit facilities would have affected the landlocked Himalayan countries, which rely considerably on Bangladesh’s port for overseas trade.

Alternative routes to connect the Northeast with the Bay of Bengal

In adverse geopolitical conditions, seeking alternatives beyond immediate neighbours becomes imperative. As ties remain strained with Dhaka, New Delhi’s decision to develop the ‘Shillong-Silchar Corridor’ exemplifies such strategic recalibration. On April 30, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs, chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, approved a proposal for the development, maintenance and management of a 166.80 km greenfield high-speed corridor from Mawlyngkhung in Meghalaya to Panchgram in Assam. Beyond improving intra-Northeast connectivity, the corridor holds the strategic potential to link this landlocked region to the Bay of Bengal via Myanmar. This prospect allows New Delhi to circumvent Bangladesh and provide the Northeast with maritime access for overseas trade and connectivity.

For so long, Bangladesh has been considered the most convenient, if not inevitable, transit to link the Northeast with the Bay of Bengal, due to its geographical position and the history of partition. India’s decision to develop the Shillong–Silchar Corridor reflects New Delhi’s intent to reduce its reliance on Bangladesh, given the recent political volatility in Dhaka that has raised concerns about the stability of its investment climate and the new administration’s perceived insensitivity to India’s strategic imperatives. Simultaneously, it opens avenues for enhanced engagement with Myanmar through the Kaladan Multimodal Transit Transport Project, thereby reinforcing alternative connectivity routes to the Bay of Bengal. In doing so, it challenges the assertion made by Mr. Yunus regarding the Northeast’s dependence on Bangladesh, while advancing India’s efforts to deepen ties with Myanmar — a key partner in its Act East strategy.

Questions for future

There is thus a significant transition from India and Bangladesh capitalising their geographic interdependence to foster connectivity, to New Delhi exploring alternative channels that lie beyond Dhaka to realise its connectivity aspirations. Political will is central to fostering cooperation. The inevitability of geography and being neighbouring countries does not foreshadow favourable bilateral ties. That is always a diplomatic choice. As India and Bangladesh meander into a new landscape of bilateralism, some questions demand attention. Will India and Bangladesh be able to promote a stable neighbourhood without consideration of each other’s strategic sensitivities? How will the strain in ties with Bangladesh affect India’s foreign policy and regional organisations such as BIMSTEC and SAARC? Lastly, how far can an interim government, primarily tasked to ensure a smooth transition to an elected administration, pursue strategic shifts that impact long-standing bilateral ties?

Sohini Bose is an Associate Fellow at Observer Research Foundation (ORF)