Beijing, with a yearly average air quality index (AQI) of 144, was as polluted in 2015 as Delhi is today (Delhi’s average is 155 for 2024). But in the interim, Beijing has managed to cut its pollution level by one-third with the most significant fall spanning between 2013 and 2017 (Chart 1). To be sure, Beijing’s pollution control programme dates back to 1998 which laid the foundation for this aggressive last phase of the programme, which was termed a “war against air pollution”.

Why discuss Beijing in the context of Delhi?

Beijing is the capital of an emerging economy, as is Delhi. So, if Beijing could manage what it did at its stage of development, Delhi could and needs to, as well.

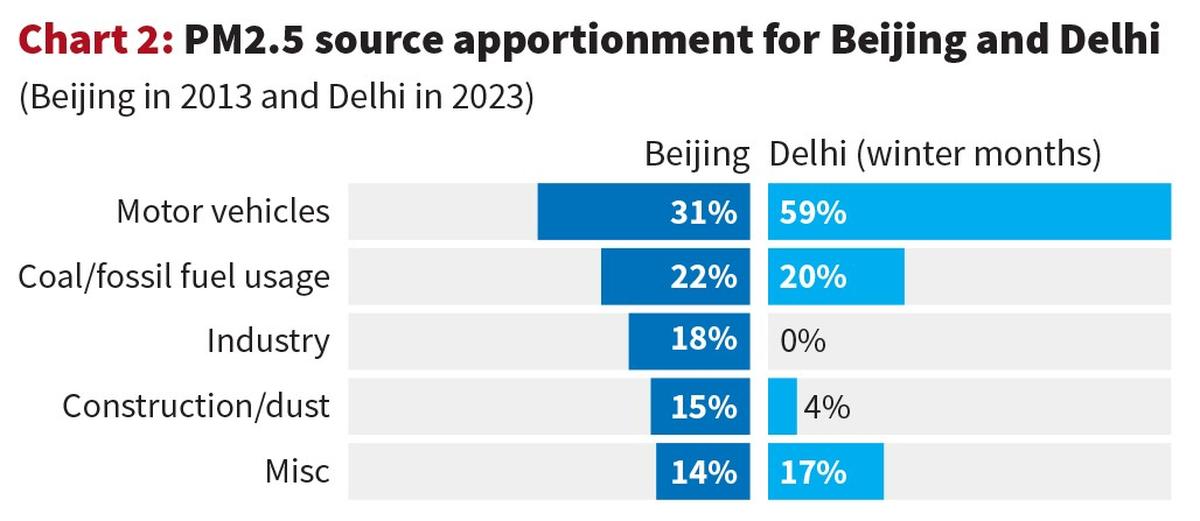

There are many similarities between Beijing in 2013 and Delhi today. Chart 2 compares the sources of pollution for the two cities.

For Delhi, we have used the winter months’ data because that is the most updated emission inventory available. Moreover, much like Beijing, the regional contribution to pollutants by neighbouring areas/States of the national capital region (NCR) is also high, especially during the winter months. While local emissions need to be controlled, without a concerted collective effort by the entire NCR region, just as Beijing achieved, it would be difficult to win this battle against air pollution.

What did Beijing do?

With rapid economic growth in Beijing, the ambient concentration of pollutants increased rapidly by the late 1990s. By 2017, Beijing’s energy consumption had grown by 74% compared to 1998. Unfortunately, a rapid increase in urbanisation and energy consumption meant higher emissions of pollutants. Things were particularly made worse because the heating in Beijing’s residential properties was heavily coal-dependent.

Beijing’s 20-year anti-pollution programme can be divided into three phases — 1998-2008; 2009-12; 2013-17. One common theme that ran through the entire effort was not shock-and-awe but a careful and slowly built-up plan with people’s participation, which was run autonomously by the local government of Beijing.

Sources of pollution in Beijing were broadly identified as energy structures and coal combustion (contributing 22% to PM2.5), transportation structures (31%), and construction and industrial structures (33%).

For the first source, three steps were taken — ultra-low emission renovation and clean energy alternatives in power plants, renovation of coal-fired boilers, and elimination of civil bulk coal consumption used for residential heating.

For transportation infrastructure, the government first retrofitted cars and public service vehicles with diesel particulate filters (DPF) and gradually tightened emission standards. Then it went for scrapping, through subsidies instead of decree, of ‘yellow-labeled’ vehicles (heavy pollutant-emitting vehicles). Subway and bus infrastructure was overhauled and expanded at a rapid rate, along with optimising the urban layout.

As for the industrial and construction activities, tightening environmental requirements, intensifying end-of-pipe (EOP) treatment, eliminating obsolete industrial capacity, creating a green construction management model, efficient washing facilities, and implementing video monitoring with penal action against violators of construction sites were some of the steps taken.

The last leg of the plan (2013-17) especially focused on the need for regional cooperation, with five adjoining provinces around Beijing coming together to chalk out a collective plan for reducing ambient pollution in the region. This cooperation had a remarkable effect in reducing the level of pollution.

What did Beijing achieve? And how?

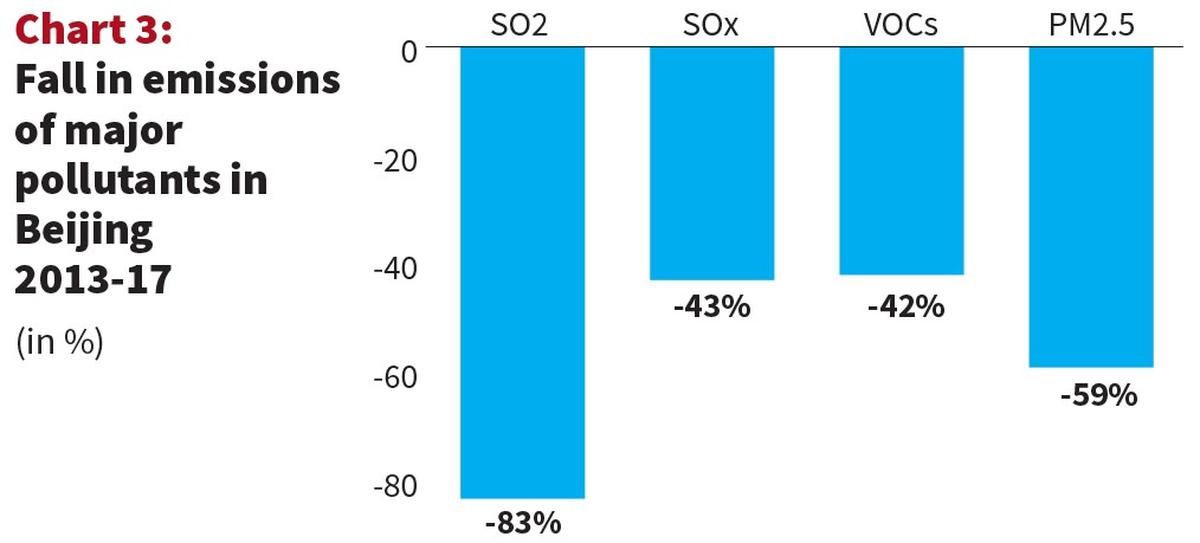

As a result of this meticulously planned strategy at multiple levels, sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxide, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and PM2.5, the four major pollutants targeted under the policy, fell by 83%, 43%, 42% and 59% respectively between 2013-17 (Chart 3). Since most activities produce multiple pollutants, albeit to differing degrees, targeting a source meant reducing all the associated pollutants.

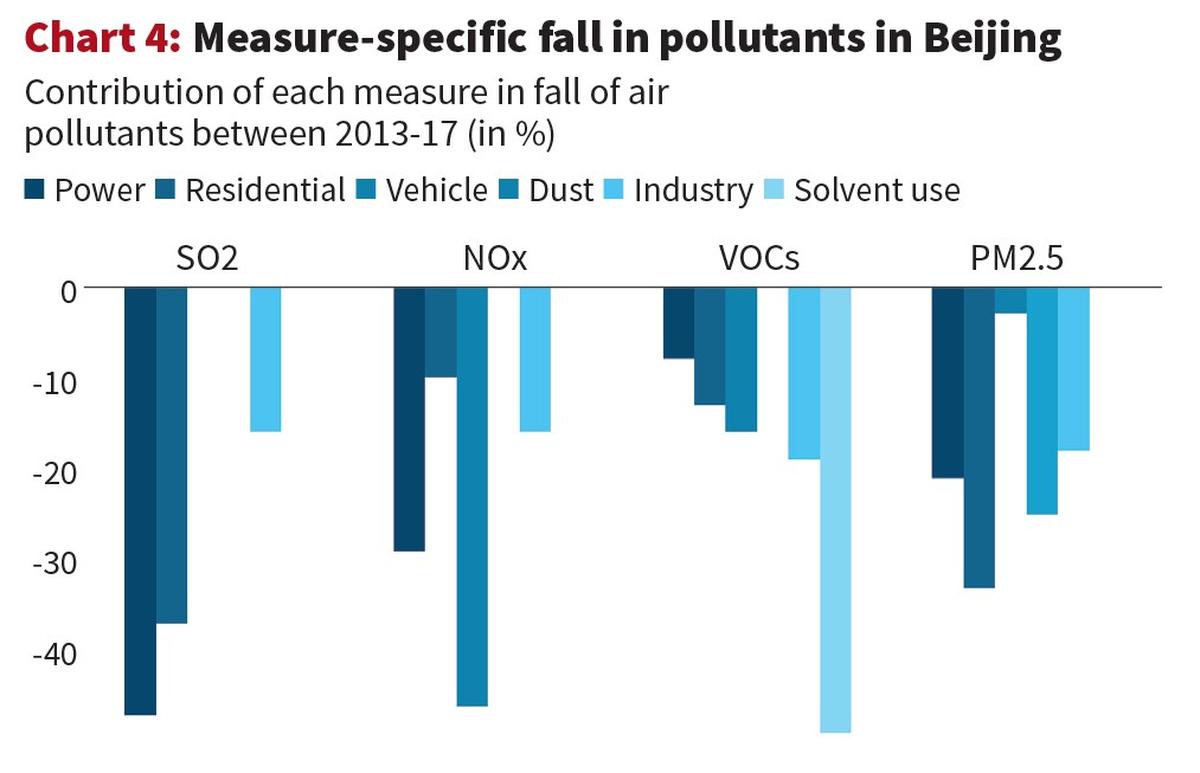

Chart 4 shows how by targeting each source, multiple pollutants were controlled.

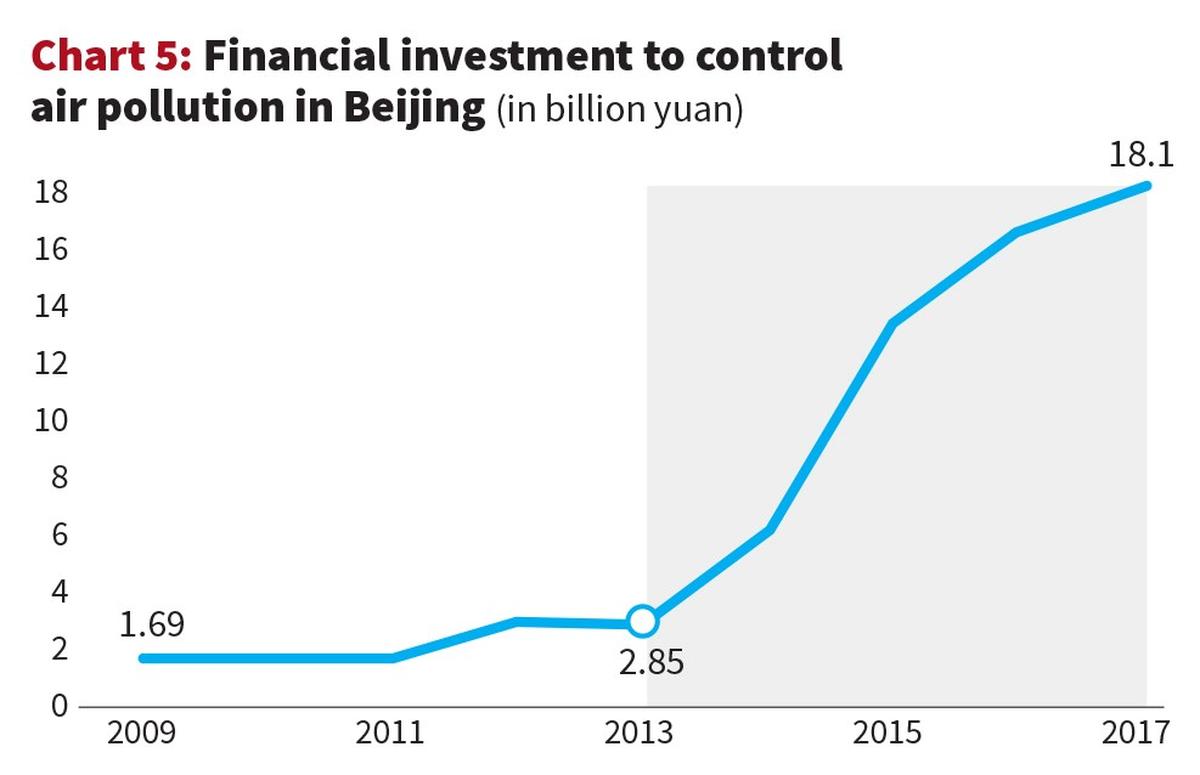

The single most important factor in Beijing achieving its goal, apart from planning to the last detail, was the financial investment that the government committed to.

Chart 5 shows a whopping six-time jump in investment within just four years. All the steps enumerated above required heavy investment and the government did not shy away from making and fulfilling those commitments.

What can Delhi learn from the Beijing experience?

There are ideas galore on controlling pollution, and Beijing is a perfect example to learn from. We list some here, there are more.

Firstly, since private transport is the biggest contributor to local pollution, an efficient and comfortable bus-metro integrated transport system needs to be in place. Delhi’s DTC bus fleet is not only old but also grossly inadequate for a population of this city’s size. The metro is an excellent means of transport but is quite expensive, with almost zero last-mile connectivity provided by the State. Old vehicles need to be scrapped at the earliest through a well-thought-out subsidy-for-scrap programme, instead of banning them. Exclusive cycling and walking lanes should be built throughout the city. Other ideas, such as cross-subsidisation through affordable public transport and expensive private transport (cars and motorcycles) using congestion or high parking charges, as well as separate fuel costs for the two modes of transport, could be experimented with. An urban layout is needed where places of work and residence are brought closer, alleviating the need for long-distance travel.

Secondly, Delhi’s electricity is still supplied primarily through coal fired plants. The energy system needs a serious overhaul both from the sides of supply and demand. Subsiding solar roof tops and connecting it to the grid with electricity bill discounts could be one such step in this regard.

Thirdly, much like the Beijing plan, Delhi needs to coordinate with neighbouring regions, instead of being at loggerheads, to control other sources which originate in these regions. Such a step may work in their collective interests.

Last but not least, the people of Delhi need to fight for the right to clean air and hold the government accountable instead of normalising poor AQIs as being better than severe ones. Prolonged exposure to pollutants, even in the poor AQI zone (for a larger part of the year), may be as dangerous as a short period of severe AQI in October and November every year. This change in attitude itself may go a long way in building pressure on the governments.

Unfortunately, it is not the lack of ideas but political will which is stopping Delhi from acting. It is the same reel playing out every year. Air in the very harmful zone for weeks with schools closing down, the young and the elderly gasping for breath through the day is the new normal in the winter months in Delhi. And what does the government do? The Centre blames the State and vice versa while they have both been in office for a decade. Neither of them is serious or even vaguely interested in solving the problem. Schools, offices, and individuals look for solutions in the form of air purifiers, but private protection for a public bad is by definition exclusivist, with especially the disadvantaged, who contribute the least to the problem, getting a raw deal. Delhi deserves a better response. It is high time that the government, both at the Centre and the State, listened and acted.

Rohit Azad is a faculty at the Centre for Economics Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and Shouvik Chakraborty is a Research Assistant Professor at the Political Economy Research Institute, Amherst, U.S.

Published – December 12, 2024 10:46 pm IST