On the hot afternoon of December 29, more than 300 women at Kesampatti village in Melur taluk in Madurai district, stand in a circle. Most of them are daily wage labourers or farm workers and are of different ages. Clad in colourful sarees, the women clap their hands, sing, and dance in a synchronised fashion. This is kummi, a folk dance that is performed in parts of Tamil Nadu.

However, this is not a festival or religious event, when kummi is generally performed; it is a protest site at the entrance of the village. Through performance, the women are agitating against the Union government’s proposed extraction of tungsten, a rare element found in this region, which is critical for automobile and defence industries and green energy technologies. “Enga mala sami kavalkarana irunthu makkalayum nilathayum kappan (Our hill god being a protector will protect both our people and land),” goes their kummi song.

A. Kalpana, who has never participated in a protest, says, “Our art, religion, food, culture, and tradition are interlinked with this landscape. Without our land, we will become nothing.”

The kummi protest is part of the weekly agitations that have been organised by activists and the residents of panchayats in Melur taluk since November 7, 2024. The Ministry of Mines announced that it had granted tungsten mining rights in eight blocks, spanning 5,000 acres, through an auction, to Hindustan Zinc Limited, a subsidiary of Vedanta Limited, a listed company. The Melur region, proposed for mining, includes the villages of Arittapatti and Nayakkarpatti, which are rich in scheelite, a key source of tungsten, and are also home to several heritage sites.

On November 23, more than 20 panchayats of four panchayat unions in Madurai passed resolutions against the project. A few days later, Chief Minister M.K. Stalin urged the Modi government to cancel the award of tungsten mining rights in Madurai district and said that he would not allow it as the people were opposed to it. The Ministry, in turn, issued a statement saying “inputs were taken from the Government of Tamil Nadu before the block was put up for auction.”

C. Jeeva, a resident of Kesampatti and an organiser of the protest, says, “Though we have organised similar protests and rallies against granite quarrying in the Melur region in the past, we know that the struggle this time is against the Union Ministry and one of the biggest conglomerates in the world. It is going to be a tiring and prolonged battle, but we will persist.”

Anger in Arittapatti

K. Selvaraj, 44, an environmental activist based in Kambur village near Melur taluk, is critical of the Ministry’s decision of naming the project after a hamlet of about 20 houses.

“By naming it after Nayakkarpatti, they made sure that it did not get immediate attention from the public. If it had been named Melur or Madurai tungsten block, the opposition to this would have been instant and more intense,” he says.

Selvaraj has been part of protests earlier. Last year, hundreds of residents from over 15 villages in Melur taluk staged a sit-in protest at Sekkipatti village condemning the district administration for inviting tenders for the operation of granite quarries in the taluk. This time, he was among the first few to oppose the project through petitions and Gram Sabha resolutions. “I went around telling people about the problems that the project will cause, and organised meetings to discuss protests and legal remedies,” he says.

Watch: Why is Tamil Nadu opposing tungsten mining? | Focus Tamil Nadu

Selvaraj says no panchayat president opposed the resolutions. “Since, this is a government project, some of the presidents were hesitant to record our resolutions, but eventually they agreed,” he says.

The protests and resolutions, Selvaraj says, were necessary, since Nayakkarpatti block comprises 11 villages, including Arittapatti, a biodiversity heritage site.

A. Durka Devi, 26, the only postgraduate degree holder from Nayakkarpatti village, says the seven rocky granite hills that include areas of the Koolampatti, Arittapatti, Nayakkarpatti, and Meenakshipuram villages have historical significance.

“These hills contain evidence dating back to the 16th century Pandya kingdom. They also feature several megalithic structures, rock-cut temples, Tamil Brahmi inscriptions, and Jain beds. If not for these historical records, this place would have been turned into stone, dust, and sand long ago,” she says.

Noting the importance of the Melur region, a group of archaeologists, including C. Santhalingam, released a statement supporting the people’s protest against the mining project. In it, they wrote that two Brahmi stone inscriptions dating back 2,300 years could be found in the Kazhinja malai, one of the seven hills. They also said that the Laguleesar sculpture in a 7th-8th century rock cut temple in the area was rare and should never be disturbed.

Devi says Aritapatti was notified as Tamil Nadu’s first biodiversity heritage site in 2022. The site covers the Arittapatti and Meenakshipuram villages in Madurai district. “It houses around 250 species of birds, including three raptors — the Laggar falcon, the Shaheen falcon, and Bonelli’s eagle; 200 natural spring ponds; and three check dams,” she says, the information at her fingertips. The region is also home to wildlife, including the Indian pangolin and slender loris.

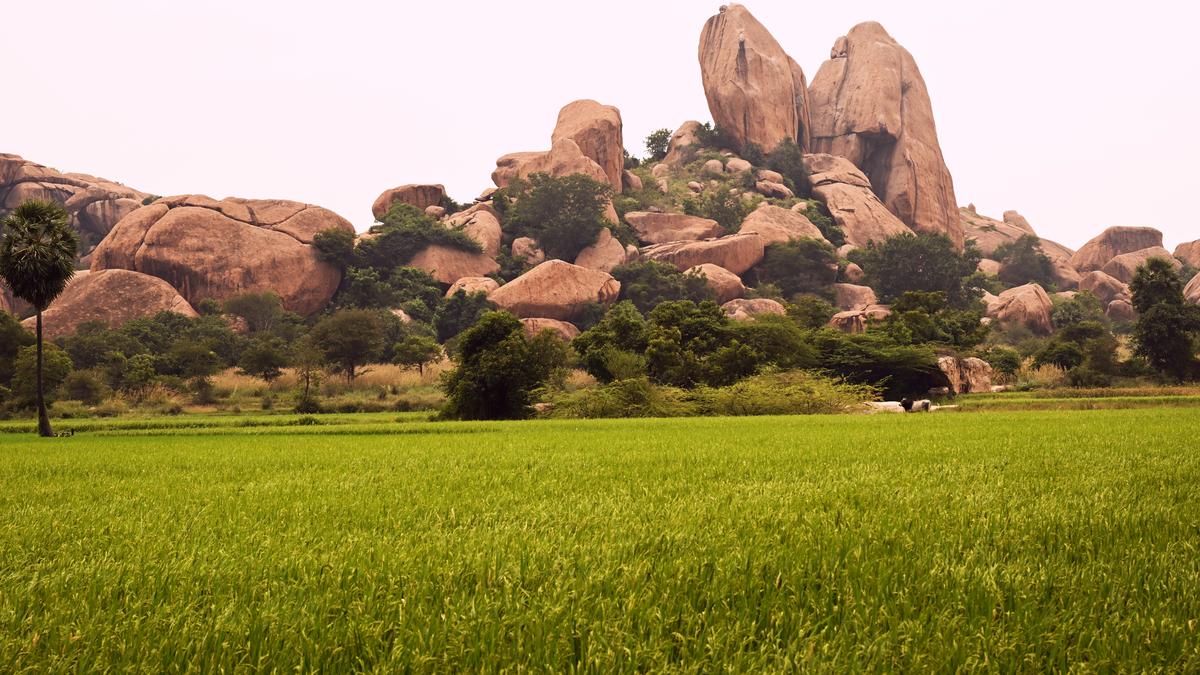

The rocky hills stand tall and are surrounded by green patches of farmland. The farms, which are mostly fed by the Mullaperiyar dam, use the ponds as their water source, say residents.

Given the massive opposition to the project, especially in Arittapatti, on December 24 the government asked the Geological Survey of India to redefine the boundaries of the Nayakkarpatti block by excluding the biodiversity heritage site from it. It also asked the Tamil Nadu government to keep the process of issuing the Letter of Intent to the preferred bidder, Hindustan Zinc, on hold for the time being.

But the resurvey order caused more fear. The residents say they had thought the project was coming to a halt altogether as the Tamil Nadu government had passed a resolution in the State Assembly on December 9 saying it would not allow the mining project.

Selvaraj sits on one of the hillocks near Arittapatti along with villagers to discuss the next steps. They decide that they will embark on a 25-kilometre-long protest march from Narasingampatti in Melur taluk to Tallakulam in Madurai city on January 7.

Turning away from the villagers, Selvaraj says the entire population of Melur taluk depends on land for their livelihood, as their primary income is through farming and livestock management. But more importantly, the people consider the hills sacred, he says.

“Humans who did some sort of sacrifice for the village or to the people became gods. And they now reside in these hills, so we celebrate them and worship them,” says K. Revathi, 25, an agricultural worker from Nayakkarpatti.

Devi says she does not understand the Union government’s plan. “What is the point of saying they will leave out Arittapatti alone when they want to destroy the rest?” she asks.

The State government’s say

There is also suspicion about the State government’s position and motives. I. Selvam, 42, a farmer in Arittapatti, says while the State government had initially said it was against the mining project, Ministers have been trying to prevent villagers from passing resolutions at Gram Sabha meetings.

“Knowing that the Gram Sabha decisions will have an effect on the implementation of the project, Commercial Taxes and Registration Minister P. Moorthy (representing Madurai East) influenced the villagers and told them not to pass resolutions during meetings,” Selvam alleges. “The people know that the State government had no say in projects like these. But our hope is that the government will at least stand by our side.”

In an order dated October 21, 2024, the Ministry of Mines had said that it had been empowered to auction blocks for the grant of an exploration license under Section 20A of the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957.

Citing the amendment, R.S. Mugilan, an environmental activist known for his agitation against the Sterlite copper plant in Thoothukudi and the Kudankulam nuclear power plant in Tirunelveli, says the State government’s authority over resources has always been limited in matters of national interest, such as nuclear power.

“This was evident yet again when Union Minister of State R. Sudha asked in the Lok Sabha whether the Union government would ban oil and gas exploration activities in the delta districts, which have been declared as special agricultural zones by the State government,” says Mugilan. “The Union Minister of State, Kirti Vardhan Singh, replied that certain areas were notified as eco-sensitive zones or areas based on proposals from States, but said that there was no such proposal from the Tamil Nadu government.”

Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam leader, Vaiko, staging a protest at Melur taluk against the proposed project in Madurai.

| Photo Credit:

G. Moorthy

Mugilan says all political parties want to play the blame game. The All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam has opposed the project through protests and rallies and has also held the ruling Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam government responsible for auctioning the mine. The BJP has slammed the two Dravidian parties for “misleading” the people. Bharatiya Janata Party State President K. Annamalai, who finds himself in a tricky spot, has said he has appealed to the Minister for Mines, G. Kishan Reddy, to keep the project on hold. Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam leader Vaiko has accused the Centre of awarding the tungsten mining contract to Hindustan Zinc without consulting the State government. “In the midst of this, political parties fail to understand the toll that so-called developmental projects take on the lives of the people,” he says.

He explains the potential effects of the tungsten project: “Studies in China show that communities near tungsten mining sites have experienced elevated levels of tungsten in soil and water, leading to increased health risks. What assurance do the people of Madurai have that their health and lives will be fine?”

Mugilan cites the Bhopal gas tragedy as an instance of government apathy. “It took 40 years for the government to remove hundreds of tonnes of toxic waste from Bhopal from the chemical factory. This shows India’s backwardness in dealing with such tragedies,” he adds.

After submitting a petition to G. Kishan Reddy during the last Parliament session, Madurai MP Su. Venkatesan organised a protest along with fellow cadres of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) in Melur to inform people about the importance of their role in opposing the project.

“Though the resolution passed by the Tamil Nadu government in the Assembly may have political value, it has no legal value owing to the amendment passed in 2023 [to strengthen the extraction and exploration of critical minerals],” Venkatesan explains. As the Union government has turned a deaf ear to the people’s demands, the people must keep protesting, he says.

The need for critical minerals

M. Vetriselvan, an advocate and a member of Poovulagin Nanbargal, an environmental organisation based in Tamil Nadu, says, “Critical minerals, which were included in the Act in 2023, have geopolitical value. Following the U.S. government’s 2018 policy to secure critical minerals to shift the country’s dependence from fossil fuels to renewable energy, the international market for critical minerals such as tungsten has been opened. That is why the Indian government has chalked out ways to secure critical minerals located in various places in the country.”

Vetriselvan says if the State government truly objects to the project, it will have to pass a law to protect the natural resources of Melur taluk, similar to what it did to safeguard the delta region.

Selvaraj remembers how the protesters confronted representatives of the Geological Survey of India when officials visited the areas to study rocks. “It ended in an argument. We were unaware that the study was the first step towards destroying our livelihoods,” he says.

He says in addition to the Nayakarpatti tungsten block,another 35,000 hectares of land in Kambalipatti, Rayarpatti, and Rajanampatti in Melur taluk have been studied and are ready to be auctioned. “Now, all they have to do is sanction the project,” he says.

Mookayi, a woman in her 70s, standing next to Selvaraj, points to a hilltop and narrates the folktale of a village informer, Vemban, who protected the villagers from robbers and invaders. She says he starved to death on the same hill after the robbers pushed away the ladder that he would use to climb to the hilltop. To honour his life, the hillock was named Kazhinja malai.

Mookayi believes that Vemban still protects the village from the hilltop. “He will prevent this region from turning into dust,” she says.

palanivel.rajan@thehindu.co.in

Published – January 04, 2025 02:51 am IST