For many Bengalureans, Indiranagar is their weekend leisure date at its many well-known pubs, restaurants or shops. But for Jayalakshmi Sriguha, now 62, it has been home for almost half-a-century.

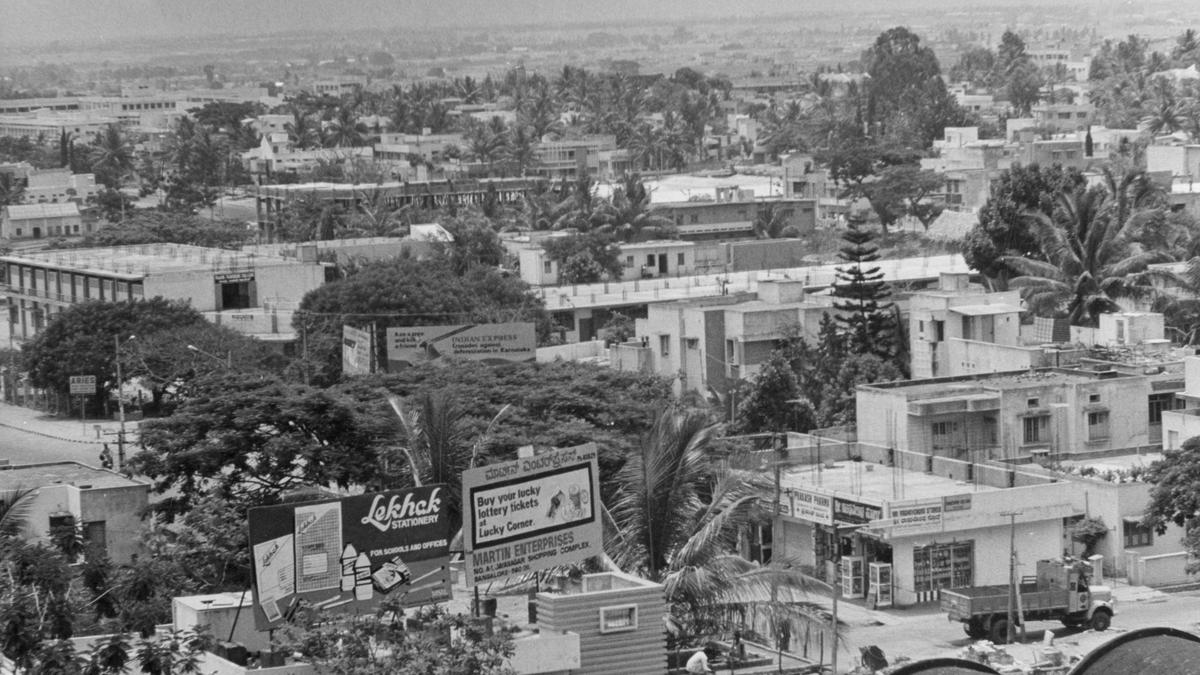

Once sought-after residential localities, prime old areas of Bengaluru are seeing rapid redevelopment, turning them into bustling commercial spaces.

| Photo Credit:

K. BHAGYA PRAKASH

When she moved into their house off Indiranagar 12th Main from Ulsoor in 1977, many people asked her family members why they had chosen an area so forsaken. “I was in class 10. We didn’t know that roads were going to come up around us. This was part of a village called Doopanahalli and a laidback place. We were scared to come home after 6 p.m.,” she recalls.

The tuition teacher says she has seen the area grow before her eyes, remembering how they would marvel at the many beautiful houses being built on 100 Feet Road.

“As we were building our house, the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) planted so many trees. In the 1980s, the cross roads came up and plots were sold. I got married in 1984 and moved out of the country. When I returned in 1997 too, there were quite a few empty plots. In 1999, I bought a plot 10 houses away from the house where I grew up,” she said.

A bygone era

She reminisces about how residents would play badminton on the road and on empty plots, and how they could see flights land and take off from HAL airport, and even the utility building – then the tallest in the city. “The BPO culture changed everything. Around the mid-2000s, it just crept under us and things just ballooned. I still don’t understand how 12th Main became a commercial access road. I still know a lot of people here, but there are very few locals. We are struggling to keep at least our road residential. I tell people this is the only place I have. It is unfortunate what it has become despite our fight. Even if it was commercial, it would have still worked if the basic rules such as parking facilities were followed,” she says, while recalling how she battled sewage backflow in her house only a few days ago.

Once a sought-after residential area, Indiranagar today is among the prime commercial hubs of Bengaluru. Its story is the same as many other prime old residential hubs of the city. With land parcels becoming scarce in the core areas of the city, real estate players across the board report massive redevelopment taking place in these prime areas.

Once sought-after residential localities, prime old areas of Bengaluru are seeing rapid redevelopment, turning them into bustling commercial spaces.

| Photo Credit:

K. BHAGYA PRAKASH

Digbijay Das, Senior Director, Valuation Services, Colliers India, said apart from the Central Business District (CBD) region, comprising M.G. Road, Richmond Road, Residency Road, Infantry Road, Cunningham Road, Sankey Road, Vittal Mallya Road, and Ulsoor, standalone residential developments in Koramangala, Indiranagar, Jayanagar, J.P. Nagar, etc., are being redeveloped into commercial office, retail, and mixed-use development areas. “Increase in commercial activity has led to a rise in land price and this has prompted the redevelopment. Redevelopment is taking place to fulfill the burgeoning demand for commercial office space, retail, and mixed-use real estate in CBD region which is starved of vacant land for new development,” he said.

Once sought-after residential localities, prime old areas of Bengaluru are seeing rapid redevelopment, turning them into bustling commercial spaces.

| Photo Credit:

K. BHAGYA PRAKASH

Sudhanshu Mishra, Principal Partner, Square Yards, an integrated platform for real estate and mortgages, noted significant redevelopment across areas like Indiranagar, Koramangala, and parts of Whitefield, driven by rapid urbanisation and the growing demand for modern infrastructure. “Many older neighbourhoods, once dotted with independent houses, are transforming into high-rise apartments, tech parks, and retail complexes. This shift is largely fuelled by the city’s robust IT ecosystem and the promise of higher returns for property owners and developers.”

Once sought-after residential localities, prime old areas of Bengaluru are seeing rapid redevelopment, turning them into bustling commercial spaces.

| Photo Credit:

K. BHAGYA PRAKASH

Increasingly, residential pockets are being converted into commercial or mixed-use developments, often resulting in higher property prices and changing the neighbourhood’s character, he said, offering Mumbai’s Lower Parel and Bandra-Kurla Complex (BKC) as examples.

Natural progression

Once sought-after residential localities, prime old areas of Bengaluru are seeing rapid redevelopment, turning them into bustling commercial spaces.

| Photo Credit:

K. BHAGYA PRAKASH

“CBDs remain the cornerstone of urban economic activity, serving as pivotal hubs for commerce and corporate operations. However, the emergence of secondary business districts (SBDs) offers a complementary solution, addressing rising commercial space costs and easing congestion. This shift does not signal the end of CBDs but rather complements their role. In Bengaluru, areas near the CBD have evolved into mature commercial markets. With land availability becoming increasingly constrained, redevelopment emerges as a natural progression. By optimising land use and revitalising aging structures, redevelopment maximises the potential of the floor area ratio (FAR), enabling the creation of taller buildings or additional usable space, aligning with the city’s growing demand for modern infrastructure,” he added.

But this transformation has come at a cost, rue old-time residents of these areas who continue to live there.

Sneha Nandihal from I Change Indiranagar, a federation of RWAs, has been at the forefront of a fight against illegal commercialisation of residential areas. “In Indiranagar, there are roads that have been categorised as commercial accesses. However, they shouldn’t change the predominant nature of the residential lane. Trade licences being issued indiscriminately. In 2015, in the name of ease of business, the then Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) Commisioner issued a circular that only two documents are enough to get a trade licence for properties on the mutation corridor and commercial access – commercial tariff meters and rental agreement. The process mandates that the officials check the place of trade for sufficient parking, fire safety, and ensure there are no building or zonal violations. If these places are found to be in violation, trade licences should be null and void. But no inspections are happening,” she said, adding that there are establishments that do not have parking space for even a bicycle or have come up in setback areas [the minimum amount of open space surrounding a building that must be maintained] and basements.

Once sought-after residential localities, prime old areas of Bengaluru are seeing rapid redevelopment, turning them into bustling commercial spaces.

| Photo Credit:

SUDHAKARA JAIN

She also pointed to the many rooftop bars and restaurants that the BBMP had admitted were illegal and had issued notices to them, but there had been no follow up since.

Violation of sanctioned plans

C.N. Kumar, a resident of Jayanagar, said the situation is progressively getting worse in this old residential area too. “There are blatant violations of sanctioned plans. Independent bungalows are being converted into multiple floor dwellings. The densification of the area is leading to more traffic, and a strain on water, electricity, sewage network, and other resources. These are all old layouts and there is additional pressure on the resources now. The government should start looking at stricter implementation of existing rules,” he said.

Once sought-after residential localities, prime old areas of Bengaluru are seeing rapid redevelopment, turning them into bustling commercial spaces.

| Photo Credit:

SUDHAKARA JAIN

Property developers like Anil R.G., Managing Director, Concorde, acknowledged that residential-to-commercial redevelopment in areas like Indiranagar and Koramangala has led to significant transformations. “For instance, Indiranagar’s 100 Feet Road has evolved into a bustling commercial hub, with rental values reaching ₹100 to 150 per sqft. This redevelopment has pushed up property prices by 50% to 70%, making it a lucrative opportunity for investors. However, long-term residents often face challenges such as increased traffic congestion. Indiranagar has seen a 30% rise in traffic over the past five years, and noise pollution, altering the quiet residential charm of the area. But, redevelopment has also brought modern infrastructure, better public amenities, and increased footfall, turning these neighborhoods into thriving urban spaces that cater to a younger, tech-savvy demographic,” he added.

A. Mohan Raju, Managing Director and CEO, Kalyani Developers, also said such residential-to-commercial redevelopment in areas like Whitefield typically leads to rising property prices and a higher cost of living. “While this boosts the local economy, it can displace long-term residents as land values increase and rental rates rise. The neighbourhood may undergo significant changes, with more commercial activity, infrastructure development, and population density, potentially disrupting the peaceful, residential environment. Over time, these areas may become more vibrant and economically prosperous, but the shift could result in the loss of cultural identity and challenges like traffic congestion and sustainability issues. Urban planning will be essential to balance growth with the needs of the community.”

No master plan in place

Ironically, the city does not have a masterplan in place after the withdrawal of the draft Revised Master Plan (RMP), 2031, though the High Court of Karnataka in May, 2023, clarified that its withdrawal would not “negate all actions taken in pursuance of it, and the actions already taken as per the provisional RMP-2031 before withdrawal must be given due effect to.”

In addition, in October, 2022, the High Court of Karnataka directed the BBMP to submit a report on the exercise carried out on the use of residential premises for commercial activities in violation of the law in various parts of the city.

The Division Bench was hearing a PIL petition filed by the Wilson Garden Residents’ Welfare Association complaining that several basement floors, stilt floors, and parking areas in the residential zone are being allowed to be used by flower vendors in violation of laws.

BBMP officials were unavailable for comment. The BBMP, this financial year, revised the property tax of 15,731 properties, as the tax being paid was for residential properties despite the properties being operated under the commercial category. The total pending amount estimated after this revision was ₹398.49 crore. The civic body has so far recovered ₹114.82 crore from 9,260 properties.

‘NIMBY’ phenomenon

However, Mathew Idiculla, an urban policy expert, said different kinds of cities across the world undergo what is termed redevelopment, urban renewal, or gentrification, but in the Indian context, this process hasn’t been as stark or disruptive as seen in other parts of the world. This, he said, could be owing to multiple factors, such as complicated ownership titles and land records having multiple claimants, as well as social and emotional factors.

“There’s also resistance from old owners for their neighbourhood not to change. If you look at the regulatory side, the master planning system basically prevents any kind of commercialisation. Planning regulations are highly inconsistent with the realities on the ground, though they are made with good intentions. So, there are blatant violations and everyone wakes up when there is a disaster. There is huge dissonance between the plan of what the city should be and what the character of the city is. There is also the NIMBY (not in my backyard) phenomenon that comes into play,” he explained.

What we need, he said, is to have practical norms with some sort of consensus that are implementable, and have enforcement mechanisms. “All interest groups should be considered before forming norms,” he added.

“The densification of the area is leading to more traffic, and a strain on water, electricity, sewage network, and other resources”C.N. KumarResident of Jayanagar

Published – January 10, 2025 07:00 am IST