Tamil Nadu has an enviable track record of providing shelter to those in distress, regardless of their place of origin. But an episode in March 1990, concerning Sri Lankan refugees, marks an aberration to the State’s tradition. This episode, involving 1,612 refugees — 353 women and 400 children —remains less discussed in public discourse, and its recall assumes relevance in light of World Refugee Day falling on June 20.

Ranasinghe Premadasa’s assumption of office of the President of Sri Lanka in January 1989 made a perceptible difference to the presence of Indian Peacekeeping Force (IPKF) in the neighbouring country. Five months later, Premadasa openly demanded the ouster of the IPFK, which went there in July 1987 on the request of his predecessor, J.R. Jayawardene, following the Indo-Sri Lanka accord. The new incumbent made the demand, keeping in mind the separate anti-IPKF campaigns by two diverse militant groups, Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP, which had subsequently abandoned its militant path and joined the political mainstream) and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). After the IPKF’s de-induction commenced by the end of July 1989, the LTTE began taking control of areas in the northern and eastern regions. As the end of the political set-up in the then North East Provincial Council (NEPC), headed by A. Varatharaja Perumal of the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF), became evident, the influx of refugees to Tamil Nadu resumed in a big way.

It was against this backdrop that two ships, Harsh Vardhana and Tippu Sultan, carrying about 1,250 refugees, were not permitted for disembarkation of passengers at what was then known as the Madras harbour, on March 8 and 9. Both were diverted to Visakhapatnam, after which the passengers were taken to Odisha (then Orissa) for transit camps in Malkangiri, about 125 km from Koraput town.

A report of The Hindu, published on March 10, quoting “official and other sources,” stated that “the decision to ferry the refugees from Trincomalee to Madras was taken at a meeting” of the External Affairs Minister I.K. Gujral and the NEPC Chief Minister in New Delhi in January/February 1990. Only on the basis of that decision, both Harsh Vardhana and Tippu Sultan were hired to transport about 1,300 refugees. The report went on to state that “most probably, the Tamil Nadu Chief Minister [M. Karunanidhi] does not know about it.”

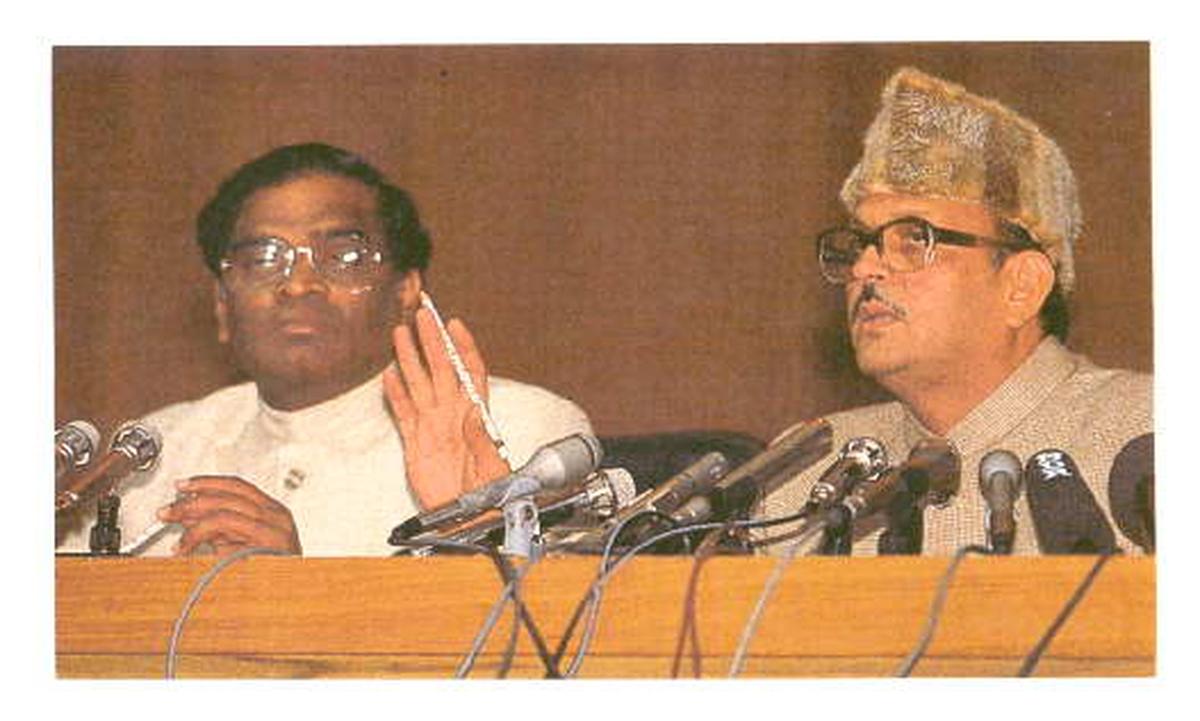

K. Premachandran, Sri Lanka’s Member of Parliament belonging to the EPRLF, was bitter about the treatment. The passengers, at the time of embarkation at Trincomalee, were assured they could disembark at Madras. “Imagine their mental agony. They were in the middle of the sea, not knowing what was happening,” the report added, quoting him as having said. P. Upendra, Union Minister of Information and Broadcasting in the National Front government led by V.P. Singh, told reporters in the city on March 9 that there were doubts whether the passengers aboard the ship were “real refugees or EPRLF cadres.”

Prime Minister V. P. Singh at his first major press conference in New Delhi, along with Minister for Information and Broadcasting P. Upendra.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

On the apprehension that the refugees could be the cadres of the EPRLF and Eelam National Democratic Liberation Front (ENDLF), who could have spirited off weapons on board the vessels, Mr. Premachandran said, “each and everyone was thoroughly checked at China Bay in Trincomalee and the IPKF also made sure that there was not a single weapon on board the ships.”

According to Anil Dhir, Bhubaneshwar-based researcher-writer, the then Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister M. Channa Reddy, who allowed the ships to drop anchor at the outer harbour of Visakhapatnam port and gave food and water, however, refused disembarkation of the passengers. A similar stand was taken by other Chief Ministers too, who did not want any trouble in their respective States. Eventually, it was Biju Patnaik who had agreed to take the refugees.

Bijayananda Patnaik, popularly known as Biju Patnaik.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

“The fact that he had been sworn in as the Chief Minister just four days earlier (March 5) did not deter him from taking such a vital decision.” Patnaik, who became Chief Minister again after a gap of over 26 years, had again responded to Singh’s request for accommodating the EPRLF general secretary, K. Padmanabha along with others, a fact acknowledged by Mr. Perumal in a recent conversation with this writer.

That Odisha, despite its modest economic condition, had come forward to accept the refugees did not go unnoticed among parliamentarians. On March 29, 1990, A.N. Singh Deo, Member of Parliament from the Aska constituency in the eastern State, called his State “a very poor State” and asked Gujral whether the Centre would bear the whole cost of providing shelter to the refugees. The Minister assured the Member that the Centre would bear the entire burden.

EPRLF leader K. Padmanabha.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

It was a fact that there were EPRLF cadres among the refugees. But they claimed that they were not “more dreadful than the LTTE militants,” Sukumar, an activist of the (EPRLF) and an inmate of the Malkangiri camps, told The Hindu, as published in a report on March 13, 1990. But Karunanidhi had reasons to justify his government’s refusal to provide asylum to the seekers. On April 26, 1990, intervening in a discussion in the Assembly, the Chief Minister cited law and order as the main reason for the move.

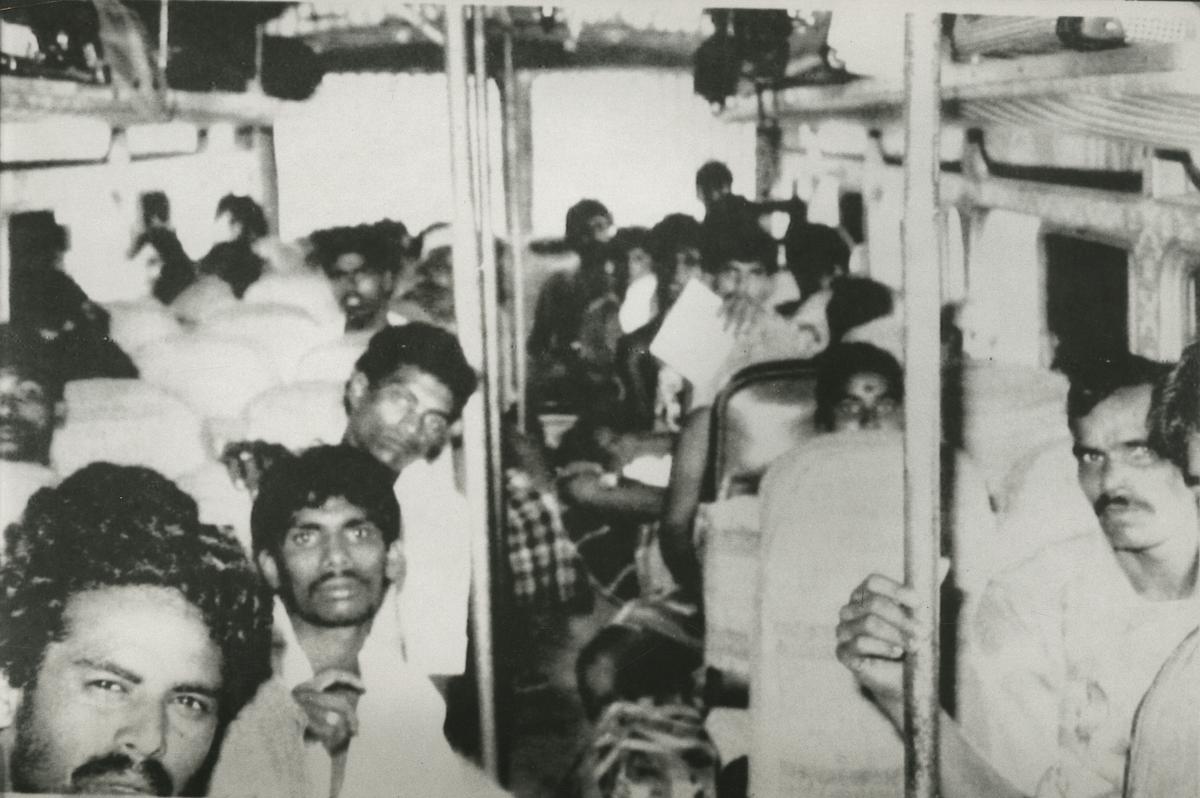

Sri Lankan Tamil refugees being transported in buses to transit camps in Malkangiri in Koraput district after their arrival at Bhubaneswar by IAF plane in March 1990.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

“He felt that militants should be kept off even from neighbouring States,” The Hindu reported on April 27, 1990. Karunanidhi had even suggested to the Central government to shift the refugees, sheltered in Odisha, to Andamans, as a majority of them were militants. A fortnight later, he told reporters that he had discussed his suggestion with Singh and Gujral.

Parliament had also discussed the refugee matter. On March 28, 1990, the External Affairs Minister told the Rajya Sabha that “hospitality does not mean open the door.” At the same time, in keeping with India’s “humanitarian traditions, we have never refused entry to refugees who, as in the present case, felt that their lives were at risk,” Gujral said. He added the refugees were brought by sea and air to the country.

Notwithstanding the Patnaik administration’s sympathetic treatment of the refugees, most of them did not find Odisha a conducive place to stay. In fact, Karunanidhi had then informed the House that the “militants” continued to arrive in the city from Orissa camps by train and they were apprehended by the police. In the middle of May, he described the refugees’ action of deserting the camps as “wrong” and contended that “of those who had come to Tamil Nadu, 190 persons who were militants were taken into custody. Other refugees, including women and children, had not been arrested,” stated this newspaper in its report on May 17, 1990.

A few days later, after a protest-fast by 111 refugees at the Central Prison who came from the eastern State, the Chief Minister ordered their release. Within a year, the number of refugees in Odisha dwindled to 218, according to the Annual Report of the Union Ministry of Home Affairs for 1990-91. [As on March 31, 1991, there were about 2.1 lakh Sri Lankan refugees living in the country.] The former CM of the NEPC recalls that a majority of those who left the camps had finally settled in the Western countries. He and his family were initially taken to Mauritius before being taken to central and northern parts of India. He now shuttles between India and Sri Lanka.

The episode ended on a further sad note, as the EPRLF’s general secretary and 14 others were gunned down allegedly by a killer squad of the LTTE on the evening of June 19, 1990, while he was holding a meeting in a flat at Kodambakkam, a busy locality of Chennai.

Published – June 11, 2025 06:30 am IST