BBC News science team

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRolls Royce has been selected to develop and build the UK’s first small nuclear power stations.

It is hoped small modular reactors (SMRs) will help meet the UK’s growing electricity demands, be faster to develop than full size reactors and create thousands of skilled jobs.

Alongside £2.5bn for these SMRs, the government has also announced £14.2bn to build a new larger scale reactor, Sizewell C in Suffolk.

What is a small modular reactor?

BBC News

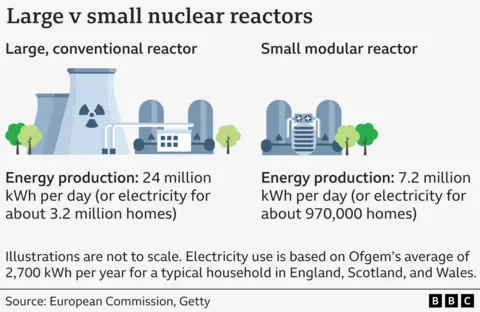

BBC NewsSMRs, sometimes called “mini nukes”, work on the same principle as large reactors, using a nuclear reaction to generate heat that produces electricity.

Inside one or more large reactor vessels, atoms of nuclear fuel are split, releasing a large amount of heat. That is used to heat water, which drives a turbine. Essentially, reactors are giant nuclear kettles.

SMRs will be a fraction of the size and have up to a third of the generating output of a typical large reactor.

The modular element means they will be built to order in factories – as a kit of parts – then transported and fitted together, like a flat-packed power station.

The aim is to save time and money

Why does the UK want ‘mini nukes’?

The government wants a secure, reliable, affordable and low carbon energy system.

In 2024, nuclear accounted for 14% of the UK’s electricity generation, according to provisional government figures. The aim is to boost that.

Along with 30 other countries, the UK has signed a global pledge to triple nuclear capacity by 2050.

But no new nuclear power station has been built since Sizewell B began operating in 1995. And most of those in operation are due to be retired by the end of the decade.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe SMR industry is in its infancy and, around the world, about 80 different designs are being investigated.

Only China and Russia have small reactors up and running.

The UK government is convinced that, with investment, SMRs will create thousands of jobs and boost manufacturing.

Initially though, both government and private investment will be needed to turn the designs into a commercially viable reality.

In the US, companies including Google, Microsoft and Amazon, with their power-hungry data centres, have signed a deal to use the reactors when they become available.

Where will small modular reactors be built?

BBC News

BBC NewsIn 2011, the Conservative government identified eight sites for “new nuclear” (larger reactors), at Bradwell, Hartlepool, Heysham, Hinkley Point, Oldbury, Sellafield, Sizewell and Wylfa.

Then, in February 2025, the prime minister said he would cut planning red tape to make it easier for developers to build smaller nuclear reactors on additional sites across the country.

Certain criteria would have to be met, Sir Keir Starmer said. No sites would be approved close to airports, military sites or pipelines. Locations valuable for nature or at risk of flooding would also be ruled out.

Great British Nuclear, a public body with statutory powers to push through the government’s nuclear plans, ran a competition to find a firm that would develop and build SMRs in the UK.

It aims to select and announce a location by the end of 2025, with the first SMR operational by the mid 2030s.

Preferred locations are likely to include old industrial sites, such as former nuclear plants, or old coal mines close to the grid.

Rolls Royce beat two American consortiums in the competition, Holtec, GE Hitachi. A Canadian company, Westinghouse pulled out.

Will SMRs cut electricty bills?

EDF

EDFThe financial controversy around the new large reactor being built at Hinkley Point C in Somerset is a perfect example of what the UK is trying to move away from. It is running a decade late and has overspent by billions of pounds.

SMRs promise to be quicker, easier and cheaper to build.

But while they will eventually be built to order, cost savings don’t kick in until designs have been finalised and modules are reliably rolling off factory lines.

So the first SMRs will probably be very expensive to build.

The cost of dealing with nuclear waste also has to be factored in. Sellafield, in Cumbria, currently deals with most of the country’s waste, but it is running out of space and costs are spiralling.

In 2024, leading nuclear scientists on a government advisory committee recommended any new nuclear power station design should include clear plans for managing waste, to avoid the “costly mistake of the past”.

Taxpayers today are still paying for Sellafield to deal with nuclear waste from the 1950s.

Nuclear industry experts the BBC has spoken to are convinced that SMRs – and more nuclear power – will eventually reduce the cost of our electricity supply.

Public attitudes to nuclear power appear to be linked to those prices. A government survey in 2024 suggested that 78% of people would find an energy infrastructure project more acceptable if they were offered discounts on their bills.

Although the government has announced discounts on electricity bills for households close to upgraded pylons, there has been no such announcement yet relating to homes near SMRs.

Kate Stephens/BBC News

Kate Stephens/BBC NewsHow safe are small modular reactors?

The International Atomic Energy Agency says nuclear power plants are among “the safest and most secure facilities in the world”.

Nuclear power’s reputation is tarnished though by high profile disasters, where radioactive material has been released into the environment – including in Chernobyl, Ukraine, in 1986 and Fukushima in Japan, in 2011.

Dr Simon Middleburgh, a nuclear scientist from Bangor University, whose research focuses on developing new nuclear materials, describes the smaller reactors that are being considered for the UK as “incredibly safe”.

“The UK’s ONR (Office for Nuclear Regulation) is treated as a sort of gold standard internationally in terms of the regulatory environment,” he told BBC News.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat about nuclear waste and security?

Some experts do have concerns about nuclear waste. Scientists from the government advisory group recently said the issue of how radioactive waste from SMRs that are in the design stage “appears, with some exceptions… to have been largely ignored or at least downplayed”.

The number and location of SMRs is also a security issue.

With more reactors spread over a larger area, potentially built on industrial sites and closer to people, Dr Ross Peel, a researcher in civil nuclear security from Kings College London, says the security burden will be higher.

Security at nuclear power stations is provided by armed police – the Civil Nuclear Constabulary. Dr Peel says the fact that existing nuclear sites generally have “miles of empty land around them” means that anyone in the vicinity arouses suspicion. If officers spot anyone they could just “look through the binoculars and ask ‘what are you doing?’,” he said.

“In urban or industrial environments, suddenly you’re trying to do security in a very different [way].”