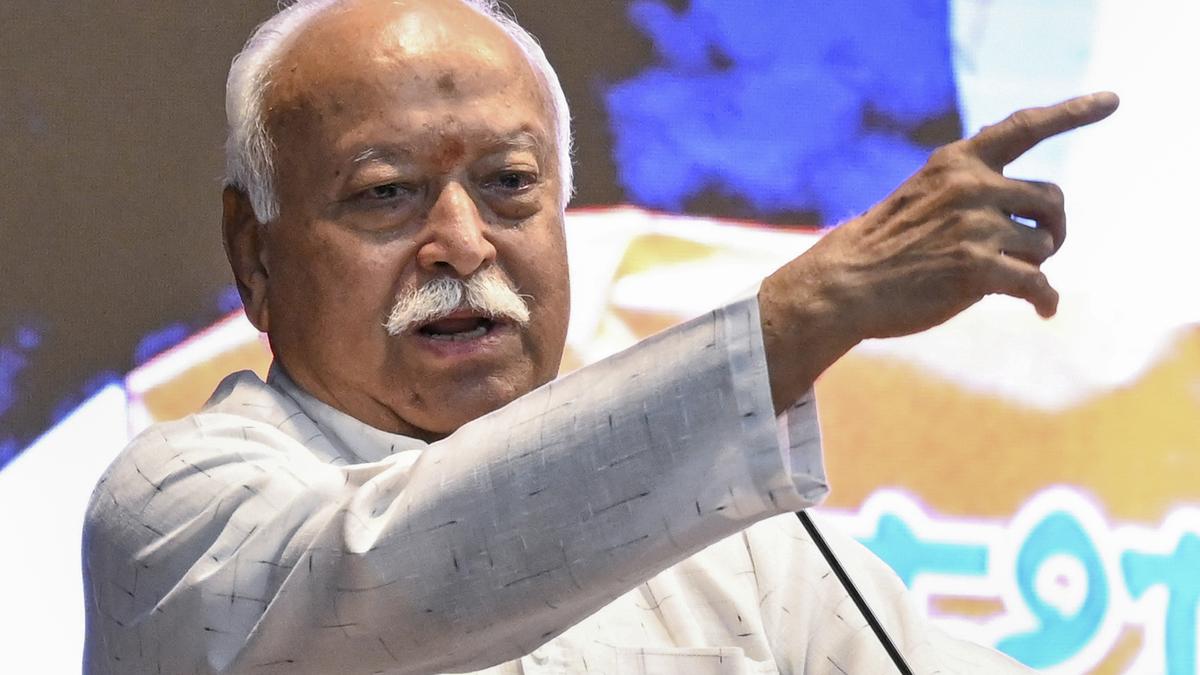

The suggestion of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) chief Mohan Bhagwat last week that leaders should step aside at the age of 75 triggered a debate. Opposition leaders saw Mr. Bhagwat’s comment as a nudge from the RSS to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who is turning 75 in September, to step down. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has maintained a studied silence on the issue. Should political leaders retire at 75? Manisha Priyam and Rahul Verma discuss the issue in a conversation moderated by Sobhana K. Nair. Edited excerpts:

Is politics across the globe and especially in India geared in such a way that politicians reach their peak only in old age?

Manisha Priyam: Do people prefer younger leaders? Yes. But why don’t they get younger leaders? This depends on several imponderables such as who controls the party machinery, who controls the party purse strings, and whether such leaders can garner resources.

We have often seen that those who reach the top hold on to their position. For instance, Lalu Prasad gained popularity at a young age. At the age of 42, he became Chief Minister of Bihar in 1990. He held on to the president’s position at the Rashtriya Janata Dal. In Uttar Pradesh, Akhilesh Yadav had to fight his father Mulayam Singh Yadav for the leadership position in the Samajwadi Party.

Regarding Mr. Bhagwat’s suggestion: this is not the first time that such a remark is coming from the RSS. This (unsaid rule) was used effectively in 2014 to allow Prime Minister Narendra Modi to (push out some older leaders and) nominate his own people at the top levels. But come September, I don’t see Mr. Modi stepping down. Today, the RSS requires the BJP machinery much more than the BJP requires the RSS. Mr. Bhagwat does not control the levers of power in India; they clearly remain with Mr. Modi.

Rahul Verma: As per one research study, less than 10% of all elected representatives globally are below the age of 35. Once you come to India, this problem actually accentuates. From the first Lok Sabha in 1952 to the current Lok Sabha in 2024, the average age of our parliamentarians has actually gone up. The number of MPs who are below the age of 40 has declined over time and the number of MPs who are above the age of 60 has increased. The problem is not that we don’t have newer faces coming into politics; the problem is, as Professor Priyam said, that the older generation of leaders does not easily cede space to younger ones. Also, perhaps, a political party itself is unwilling to bid farewell to an established leader fearing that it will destabilise the existing structure.

At the same time, I am not sure that voters would actually prefer younger politicians. It might be alright to have a 30-35-year-old MP or MLA, but I think voters would prefer older candidates for the post of Chief Minister or Prime Minister.

As far as Mr. Bhagwat’s comment is concerned, I concur with Professor Priyam that we are unlikely to see any change (regarding Prime Minister Modi’s position).

Is there any evidence which shows that nations led by younger leaders perform better?

Manisha Priyam: We have a large number of nations where there is no form of democracy, let alone change of political leadership. These include China and Russia. And we see various forms of either party authoritarianism or one-man rule in these countries.

In parallel, we also have the example of the U.K. where there have been several Prime Ministers taking office in their 40s, from Tony Blair to David Cameron. The British example tells us that when people want political change, that political change also comes by way of political leadership change. And I think we need to understand that link better.

As for India, we are now the world’s youngest nation. Our political leadership needs to reflect this aspect of our democracy. A political democracy survives by reincarnating legitimacy and renegotiating its social compact with people. On the question of age and political leadership, it must turn towards seeking younger people as political leaders. And these younger leaders should not come from established political families alone.

Rahul Verma: As per the available performance analysis of Indian parliamentarians, we know that younger leaders may not necessarily be better parliamentarians. Data shows that MPs above 60 years of age have 80% attendance in Parliament, while those below 40 have 73-74% average attendance. The older MPs ask far more questions in Parliament.

At the same time, I would add the caveat that age is not the only criteria; the health and mental faculty of a leader is equally important. Unfortunately, we have no empirical evidence to point at a direct correlation between a nation’s economic health and the age of its leadership.

Some studies have pointed out that the governance models of younger leaders may vary drastically from that of an older leadership. There can be material differences in the decisions taken by a younger or an older leader. Younger leaders are much more likely to invest their budget in economic activities of job creation and infrastructure development, while their budgets for social welfare measures, especially health-related schemes, may be low. Younger leaders do govern differently, but one can’t say if it is necessarily better.

Should there be a concrete law or regulatory mechanism to retire political leaders or to ensure that a leader who is facing mental or physical challenges steps down?

Manisha Priyam: There has been a lot of speculation around Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s health, especially after some of his television appearances. Even in the election season, his political statements were few and far between. Under the provisions of the Constitution, it would be perfectly legitimate for the Governor to seek a health report of the Chief Minister. People have a right to know if the health of the Chief Minister has been severely compromised. But in Mr. Kumar’s case, it is unlikely that such a step will be taken. I do feel this is a mockery of democratic processes. And it is not only Bihar; we have seen numerous examples in the past from various States. In Tamil Nadu, the truth about former Chief Minister Jayalalithaa’s health was concealed from the voters. The unfortunate reality is that in such cases, the people have to wait until the elections to force the change.

Though we never had a similar situation at the Centre, considering that the Prime Minister is always under the public glare, should we have a hard cut-off date for retirement? I am not sure. But we must have a transparent mechanism by way of which the electorate is kept informed about their leader’s health. Here though, the greater responsibility is of the political parties. We could have a term limit for the Prime Minister and for Chief Ministers, though.

Rahul Verma: Yes, it is desirable to have politicians who are in the best of health and are able to make sound decisions. But how do we achieve this end? Every solution to address this issue comes with its own set of problems. Prescribing a retirement age will also require creating structures that enable career progression in politics faster. That can’t be done if we have fixed the minimum age to contest elections at 25 years. Over 8,000 candidates contested the 2024 Lok Sabha polls. Less than 100 competitive candidates were below the age of 30. So just bringing in laws won’t change any of this.

Even term limits are not exactly an effective solution. Look at the U.S. It has a term limit, yet we saw Joe Biden leading the country at 81 while struggling with cognitive issues. He was succeeded by Donald Trump, who is 79 years old. But as Professor Priyam says, there is a conversation across the globe about how the citizens are perhaps entitled to have access to health bulletins of their leaders. Though, again, this isn’t exactly an elegant solution. What if the country is on the verge of a war or some kind of economic crisis? An adverse health bulletin of the leader would only add to panic in such a situation. It doesn’t even have to be a catastrophic problem; even the markets could react badly if the medical bulletin of the leader is not good. So while it is desirable that no person should remain in office if they aren’t mentally or physically fit, it cannot be regulated through legislation or any formal system.

Manisha Priyam, Sir Louis Matheson Distinguished Visiting Professor, Monash University; Rahul Verma, Associate Professor, Shiv Nadar School of Law, and Fellow, Centre for Policy Research