Climate and Science Reporter

BBC

BBCDonald Trump’s return to the White House is a “major blow to global climate action”. So said Christiana Figueres, the former UN climate chief, after he was elected in November.

Since taking office Trump has withdrawn the US from what is considered the most important global climate pact, the Paris Climate Agreement. He has also reportedly prevented US scientists from participating in international climate research and removed national electric vehicle targets.

Plus he derided his predecessor’s attempts to develop new green technology a “green new scam”.

And yet despite his history on the issue of climate, Trump has been eager to make a deal with the Ukrainian president on critical minerals. He has also taken a strong interest in Greenland and Canada – both nations rich in critical minerals.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCritical mineral procurement has been a major focus for Trump since he took office. These minerals are crucial in industries including aerospace and defence, but intriguingly, they have another major use too – to manufacture green technology.

So, could Trump’s focus on obtaining these minerals have a knock-on effect and help unlock the US’s potential in the green technology sector?

The Elon Musk effect?

Trump’s right-hand man understands more than most the importance of critical minerals in the green transition. Space X and Tesla – the companies Elon Musk leads – rely heavily on critical minerals like graphite (in electric vehicles), lithium (in batteries) and nickel (in rockets).

Dr Elizabeth Holley, associate professor of mining engineering at Colorado School of Mines, explains that each nation has its own list of critical minerals, but they are generally made up of rare earths and other metals like lithium.

She says demand is booming – in 2023, demand for lithium grew by 30%. This is being driven mostly by the rapid growth in the clean energy and electric vehicle sectors.

Within two decades they will make up almost 90% of the demand for lithium, 70% of the demand for cobalt, and 40% for rare earths, according to the International Energy Agency.

Such has been Musk’s concern with getting hold of some of these minerals that three years ago he tweeted: “Price of lithium has gone to insane levels! Tesla might actually have to get into the mining & refining directly at scale, unless costs improve.”

He went on to write that there is no shortage of the element but pace of extraction is slow.

The US position in the global race

The weakness of the US position in rare earths and critical minerals (such as cobalt and nickel) was addressed in a report published by a US Government Select Committee in December 2023. It said: “The United States must rethink its policy approach to critical mineral and rare earth element supply chains because of the risks posed by our current dependence on the People’s Republic of China.”

Failure to do so, it warned, could cause “defense production to grind to a halt and choke off manufacturing of other advanced technologies”.

China’s dominance in the market has come from its early recognition of the economic opportunities that green technology offers.

“China made a decision about 10 years ago about where the trend was going and has strategically pursued the development of not just renewables but also electric vehicles and now dominates the market,” says Bob Ward, policy director at The London School of Economics (LSE) Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

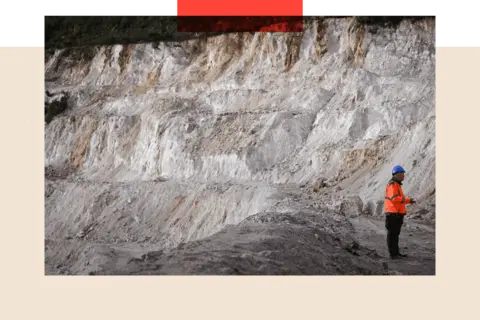

Getty Images

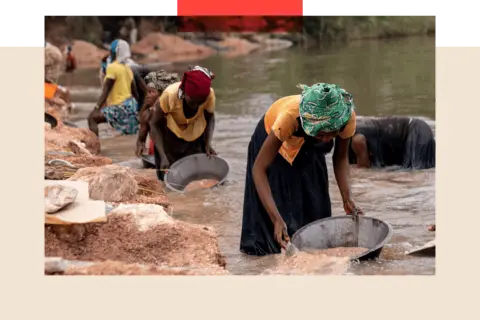

Getty ImagesDaisy Jennings-Gray, head of prices at price reporting agency Benchmark Mineral Intelligence explains that they are critical minerals because they are geologically restricted. “You cannot guarantee you will have economically recoverable reserves in every country.”

Some minerals like lithium are abundant on Earth but often they are located in difficult to reach places, so the logistics of a mining project can be very expensive. In other cases, there is dependency on one country that produces a large share of global supply – like cobalt from the The Democratic Republic of Congo. This means that if there is a natural disaster or political unrest it has an impact on the price, says Ms Jennings-Gray.

China has managed to shore up supply by investing heavily in Africa and South America, but where it really has a stronghold on the market is in processing (or the separation of the mineral from other elements in the rock).

Getty Images

Getty Images“China accounts for 60 percent of global rare earth production but processes nearly 90 percent – [it] is dominant on this stage,” says Gracelin Baskaran, director of the critical minerals security program at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

She says the country understands how important this is in economic trade – a few days after Trump introduced tariffs on China its government hit back by imposing export controls on more than 20 critical minerals including graphite and tungsten.

What is motivating Trump is a fear of being at a disadvantage, argues Christopher Knittel, professor of applied economics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

“I think what is driving this is because China is the dominant player on the processing side,” he says. “It is that processing stage, which is the high margin stage of the business, so China is making a lot of money.”

As he puts it, it is a “happy coincidence” that this could end up supporting green technology.

The key question though is whether the US is too late to fully capitalise on the sector?

A stark warning for the US

In the early days, the green transition was “framed as a burden” for countries, according to LSE’s Bob Ward.

The Biden administration was highly supportive of green technology industries through its introduction of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in August 2022, which offers tax credits, loans and other incentives to technologies that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, from battery technologies for electric vehicles to solar panels.

By August 2024 it was estimated to have brought $493bn (£382bn) of investment to US green industry, according to the think tank Clean Investment Monitor.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd yet little work was done to support upstream processes like obtaining critical minerals, says Ms Gray from Benchmark Intelligence. Instead, the Biden administration focused heavily on downstream manufacturing – the process of getting products from the manufacturer to the end consumer.

But Trump’s recent moves to procure these critical minerals suggest a focus on the upstream process may now be happening.

“The IRA put a lot of legislation in places to limit trade and supply only from friendly nations.

“Trump is changing tact and looking at securing critical minerals agreements that owes something to the US,” explains Ms Gray.

Whispers of another executive order

There could be further moves from Trump coming down the line. Those working in the sector say whispers in the corridors of the White House suggest that he may be about to pass a “Critical Minerals Executive Order,” which could funnel further investment into this objective.

The exact details that may be included in the executive order remain unclear, but experts knowledgeable with the issue have said it may include measures to accelerate mining in the US, including fast tracking permits and investment to construct processing plants.

Although work may now be under way to secure these minerals, Prof Willy Shih of Harvard Business School thinks that the US administration lacks understanding of the technical complexity of establishing mineral supply chains, and emphasises the time commitment required. “If you want to build a new mine and processing facility it might take you 10 years.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs a policy of his predecessor and one that is so obviously pro-climate action, Trump has been vocally opposed to maintaining the IRA. But its success in red states mean that many Republican senators have been trying to convince him to keep it in some form in his proposed “big, beautiful bill” – the plan to pile all of Trump’s main policy goals into one mega-bill – due to be revealed later this month.

Analysis by the Clean Investment Monitor shows in the last 18 months Republican-held states had received 77% of the investment.

MIT’s Dr Knittel says for states like Georgia, which has become part of what is now known as the “battery belt” following a boom in battery production following IRA support, these tax credits are crucial for these industries to survive.

He adds that failure to do so poses a real political threat for US representatives who are up for re-election in less than two years.

If Trump loses even just one seat to the Democrats in the 2026 mid-terms, then he loses the house majority – limiting his ability to pass key pieces of legislation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCarl Fleming was an advisor to former President Biden’s Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Advisory Committee and is a partner at law firm McDermott, Will & Emery advising clients in the clean tech and energy space. He says that despite the uncertainty investors remain confident. “In the last month my practice has been busier than ever, and this is since quadrupling last year following the IRA.”

He also believes that there is a recognition of the need to maintain parts of the IRA – although this may be alongside expansion of some fossil fuels. “If you are really trying to be America first and energy secure you want to pull on all your levers. Keep solar and keep battery storage going and add more natural gas to release America’s energy prowess.”

But the uncertainty of the US position is little consolation for its absence on the international climate stage, says LSE’s Bob Ward. “When the Americans are on the ball it helps to move people in the right direction and that’s how we got the Paris Climate Agreement.”

For those in the climate space Trump is certainly not an environmentalist. What’s clear is he is not concerned with making his legacy an environmental one but an economic one – though he could achieve the former if he can be convinced it will boost the economy.

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.