On a Tuesday afternoon, we settle down for lunch with artist Joya Mukerjee Logue, after a guided tour of her solo exhibition, Those Who Walk Before Me, at Vadehra Art Gallery. Many of us present — writers and editors — have brought along pieces that hold value of “ancestral memory”. For me, it’s an album with photographs of my mother performing on stage as a singer in the 1960s.

My mother is young, and in one photo accompanied by British-Italian pianist Charlie Mariano, Portuguese-Goan saxophonist Pobreno Dias, and a bassist who is hidden by shadows. My father had taken it. “I love the fact that you brought us these beautiful black-and-white photographs. The handwriting under each image is such a lovely touch, in the age of emails and typed fonts,” she tells me, recalling her days of writing letters to family across her diasporic existence. “I also love the dress your mother is wearing,” she adds, with a laugh.

Joya Mukerjee Logue

| Photo Credit:

Mukerjee-Logue engages with themes such as memory, nostalgia, identity, and home in her works. For her latest series, she looks back at her ancestors — her family, relatives and their friends who once lived in and around her ancestral home, Rajo Villa, in Ambala, Haryana. “I grew up in Ohio, but I have always liked the idea of timelessness that India possesses for me — it gives me a rich sense of my history,” she says. “My forefathers migrated from Behala in what is now suburban Kolkata, and then to Ambala nearly two centuries ago, in 1845, to help build a cantonment town for India’s colonial rulers.” She became familiar with her roots through regular trips to the country during her childhood and as an adult.

Behind a family archive

Mukerjee-Logue likes to call herself a bit of an archivist, memoirist and chronicler.She is also someone who is trying to document her family stories, either visually through her work or through collecting images from the family archive. So, Those who walk before me was like “a homecoming for me”, she says.

The exhibition marks her debut in India, and features 30 oil and watercolour paintings from the Cincinnati-based artist’s decade-long practice, alongside her recent body of work exploring her mixed cultural heritage and personal identity. While her mixed heritage (Mukerjee-Logue, 48, is born to an Indian father and American mother) may play a role in her choice of medium — oil on canvas is essentially a western art practice — her preoccupations are Indian.

What Remains

Her loose brushstrokes in shades of white, burnt sienna, ochre and red oxide give her work the feel of a photograph with traces of time-wear. Having said that, her creations are very painterly and not photo-realistic. It calls to mind the works of Amrita Sher-Gil, without being derivative in any way. It clearly has the stamp of her inner musings.

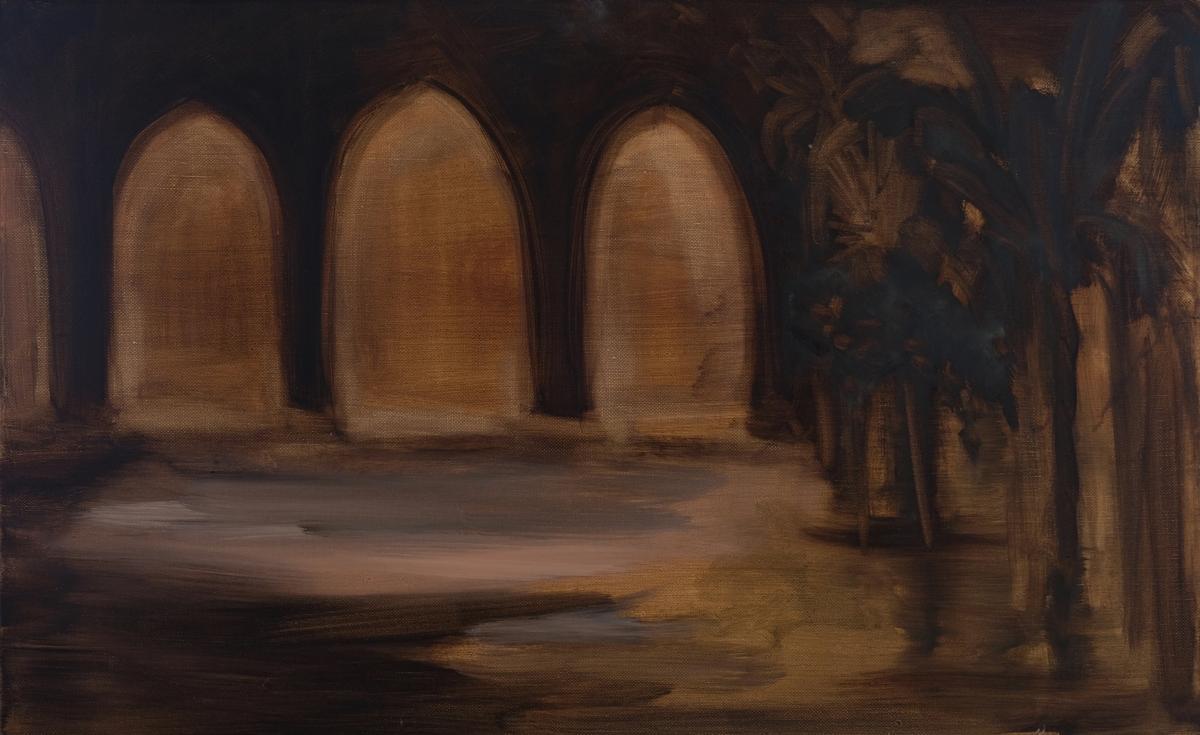

On linen canvases, she captures memories of women sweeping through the house, of swishing saris, and the palatial two-storied Rajo Villa with its pillars, arches, courtyards and terraces. Procession, a painting from the perspective of a child looking up at adults, captures four women in white saris mid-stride. Night at Sadar Bazaar, Ambala Cantt records a lively night market scene with the streetlamps lit, overloaded carts and people milling about.

Procession

| Photo Credit:

Another work, titled Portrait of the Arch, has a woman standing alone clad in a shawl and sari against a dark night sky. I cannot help but imagine that this character is a self portrait imbued with the memories of the past, but rooted in a present reality of her own making. “My personal history of Ambala is drawn from collective memory, including conversations with my 82-year-old father, an amateur documentarian who constantly recorded glimpses of his daily life through photographs and super-8 films,” she says, highlighting the multigenerational underpinnings of her works.

Portrait of the Arch,

| Photo Credit:

A grandmother’s influence

Mukerjee-Logue’s practice also comprises her ongoing research into her cultural identity. Women are a big focus of her works. Her Bengali matrilineal family left a very strong impression on her as a child. “My grandmother was strong and centred, and I think our family derived much of its cultural richness from her. She played the sitar and the violin, and appreciated art as well as spirituality,” says the artist. We get a glimpse of this in a series of intimate works titled Our Shared Sari rendered in watercolour with dry acrylic sweeps on brown paper that Mukerjee-Logue has displayed in the inner room of the gallery.

Unlike her large canvases that have a busy air to them, these works are quieter and evocative of emotions that are soft and tender. “To refresh my memories, I have referenced my family album of photographs. However, the paintings are not replications. The men, women and children that appear in them are specific and yet generic because they sweep across generations: from my grandmother and mother to my three sons.”

As lunch and our conversations draw to a close, she reminisces about her father’s super-8 films. “In one, my father is asking me what I am doing, and I say very seriously, ‘I’m hanging my painting up, can’t you see?’” Perhaps it was an indication that even a young Mukerjee-Logue knew where her path lay, and how important family and memory would be to it.

Till September 17 at Vadehra Art Gallery, in New Delhi.

The writer is a critic-curator by day, and a visual artist by night.

Published – September 12, 2024 12:33 pm IST