Who makes our salt? What is the skill needed to make it? Where does it come from? At Salt, one of the 250-plus projects of the Serendipity Arts Festival in Panjim, Prahlad Sukhtankar, sommelier and founder of The Black Sheep Bistro in Goa, invites participants to immerse themselves in stories of Indian salts. As part of the experience, they can dip into bowls of 16 types of salt. “In Tamil Nadu, salt is culture,” one photo-story says, detailing how fish and meat are salted, how it is offered to deities, and brought into the house by a bride. “Sambalam, meaning wages, derives from the combination of samba (paddy) and alam (saltpan),” a note tells us.

After an eight-month-long research with communities that make salt, Sukhtankar says what annoyed him the most was either a total disinterest in the everyday ingredient or a reverence for salts that came from abroad. American journalist and author Mark Kurlansky barely mentions India in his book Salt: A World History (2003), he says.

No one anticipated how salt pans would come into focus, when, on December 6, a couple of weeks before Serendipity, 25 people died in a fire at a Goa bar, with allegations that it was built illegally, on a salt pan.

At Salt, by Prahlad Sukhtankar, founder of Goa’s Black Sheep Bistro, participants can dip into bowls of 16 types of salt.

| Photo Credit:

Sunalini Mathew

Sukhtankar hopes the message people will take away is that “we don’t look at salt pans as empty plots of land waiting for development. It is a living intelligent ecosystem that we need to nurture and protect, and it will do the same in return”.

At the Serendipity Arts Festival, now in its 10th year, festival director Smriti Rajgarhia says, curators — this time over 35, expanding from the usual 10-12 — were given 10 “curatorial parameters”, including addressing local concerns and appealing to the youth.

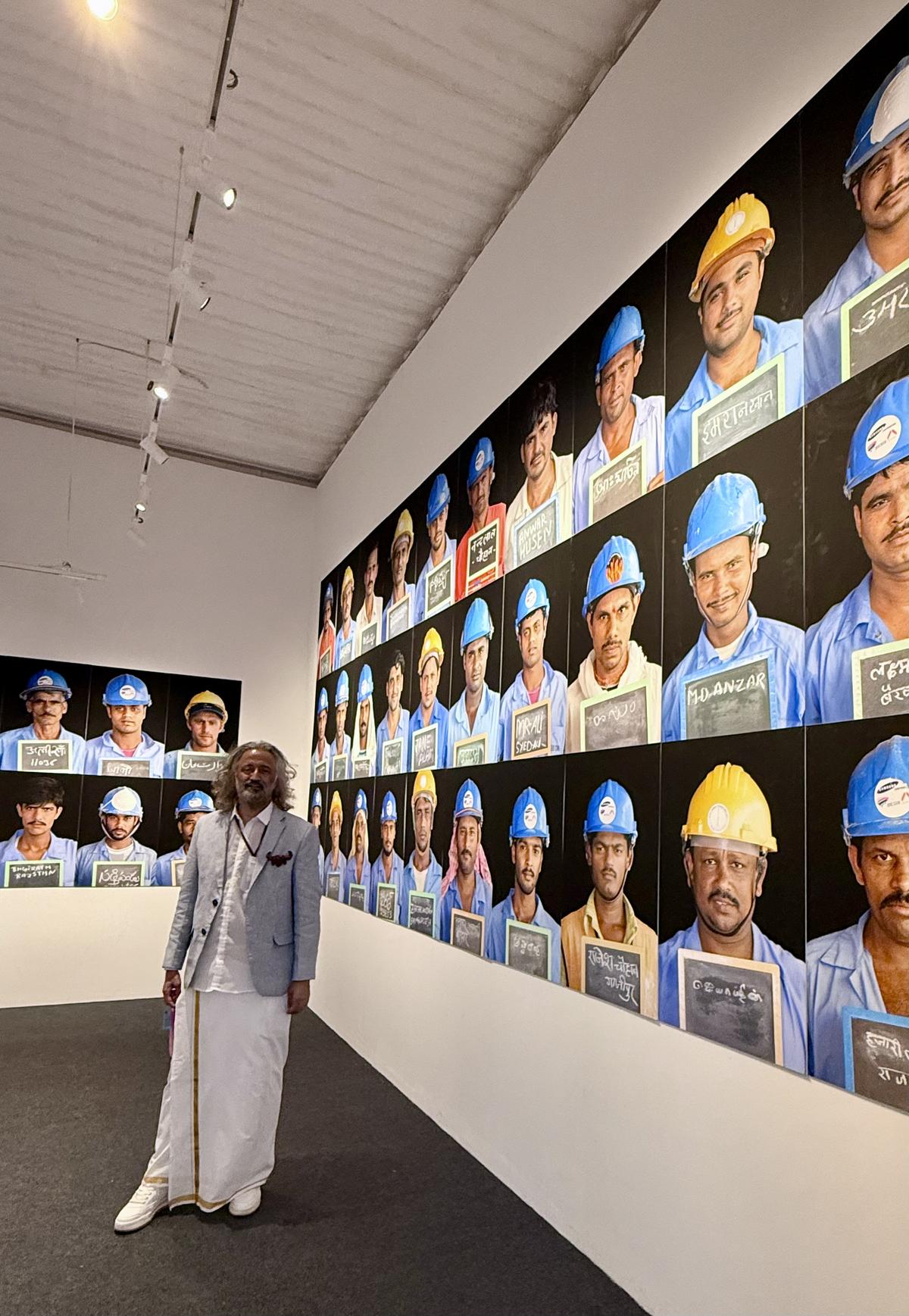

In fact, they only enunciate themes that the news throws up: of migration, oppression and war. For instance, in curator Ranjit Hoskote’s Otherland, which exhibits works by a group of four photographers, Ram Rahman addresses issues of human rights violations, through images of protest from the streets of New York, against Israel’s offences in Gaza. ‘Dump Trump & Mulch Musk’ says one poster within the photograph. Samar Jodha’s Narratives of the Nameless, about 3,500 passport photographs of migrant workers from 30-35 countries, who built the world’s tallest structure, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, forces viewers to think of labour and the loss of identity.

Artist Samar Jodha with his photographic exhibit Narratives of the Nameless.

| Photo Credit:

Serendipity Arts

Today, here, now

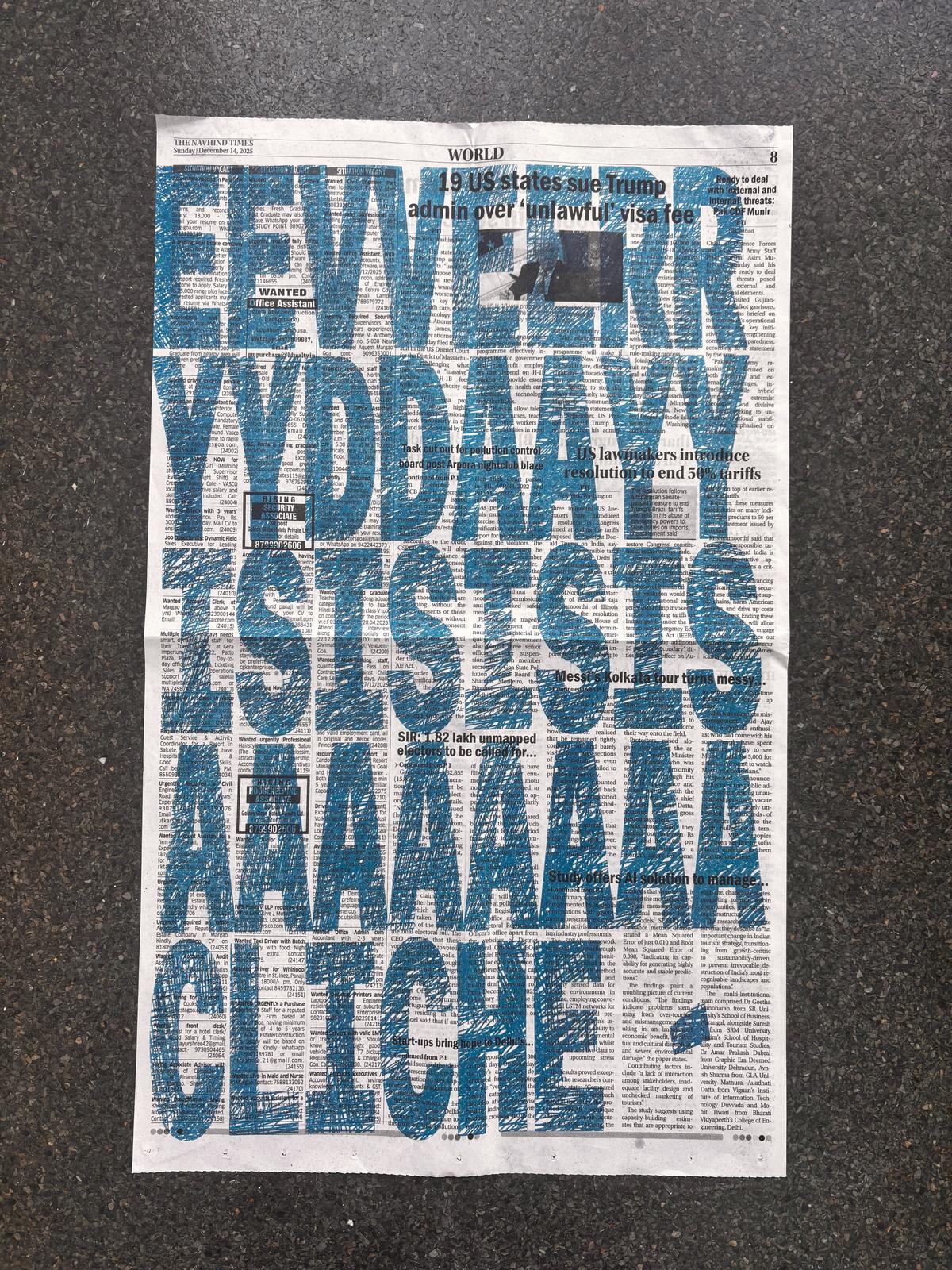

At the heritage Directorate of Accounts, one of the 13 locations in an 8km radius, Jayasimha Chandrashekar, a Bengaluru-based artist, uses a litho press, an over-200-year-old technology, to print the phrase ‘Every day is a cliché’, on the day’s newspaper. The ink goes across headlines that speak about the Special Intensive Revision, Trump’s visa fee, Goa’s nightclub blaze.

Artist Jayasimha Chandrashekar printing the phrase Every day is a cliché on the day’s newspaper on a litho press.

| Photo Credit:

Rohit Chawla

Jayasimha Chandrashekar’s print Every day is a cliché.

| Photo Credit:

Serendipity Arts

“The performance opens up layers: old rhythms of work, labour that is disconnected from the end product, the insignificance of news in a paid-media landscape, and the noise around news,” says Sumir Tagra, of the Gurugram-based artist duo Thukral and Tagra. A part of Multiplay 02 — a segment that started last year — their curation spans eight adaptive spaces or “soft systems”, offering “new ways of seeing and being”.

Melbourne-based Chunky Move’s performance You, Beauty.

| Photo Credit:

Serendipity Arts

Melbourne-based Chunky Move’s performance You, Beauty.

| Photo Credit:

Serendipity Arts

In You, Beauty, a performance by Melbourne-based Chunky Move, an inflatable expands and shrinks, much like the sea, sometimes rising to the rafters, sometimes flowing so close to the audience in a room lined with now-empty wooden cabinets. Through a puncture, viewers glimpse the innards of the inflatable, a couple of people manipulating its movement, a reminder of the innards of government agencies that control. The pink-and-purple light reflects off the glass of the cupboards that were once record holders in the 19th-century accounts building. The performer contours herself, moving with the oversize ‘balloon’, soon inviting people into it, transforming its interiors into a performance space. The white material forms a tunnel, like in Silkyara, sometimes collapsing around the dancers.

Prajakta Potnis’ Elegy in Light set on a retired barge at Serendipity Arts Festival.

| Photo Credit:

Serendipity Arts

One way governments control citizens is through surveillance. In Prajakta Potnis’ Elegy in Light, set on a retired barge, a moving spotlight highlights an iron chain, a worker’s shirt, and other everyday maritime objects. “While historically, lighthouses were considered beacons of safe passage, they have emerged as a contested symbol… Their primary function is now to act as surveillance beams,” says the project description.

Past forward

“Sometimes the future answers in whispers, not shouts,” says ‘Dr Bwanga’ over a phone, as part of a generative AI counselling session in the Lusaka-based artist Benny Blow’s own voice. ‘Dr Bwanga’ offers ‘consultations’ in a phone booth, and the wisdom is based on the artist’s research into Zambia’s traditional healers.

Lusaka-based artist Benny Blow’s Dr Bwanga installation at Serendipity Arts Festival.

| Photo Credit:

Serendipity Arts

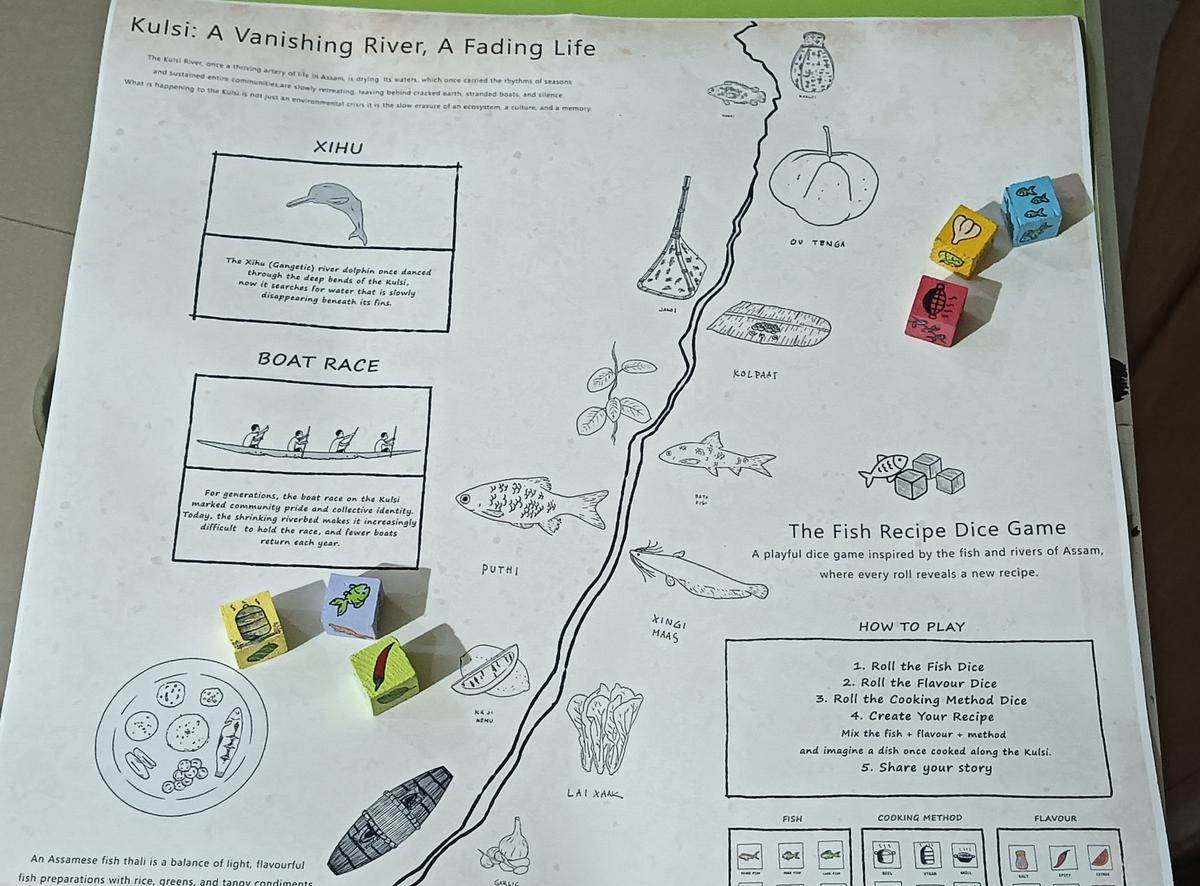

Lost Fish Recipes, co-created by Biswajit Das, supported by Serendipity through the Food Matters Grant.

| Photo Credit:

Serendipity Arts

Lost Fish Recipes, co-created by Biswajit Das, supported by Serendipity through the Food Matters Grant.

| Photo Credit:

Serendipity Arts

This reclamation of indigenous knowledge and nature is also visible at Lost Fish Recipes. At the entrance of the century-old Government Medical College, participants are encouraged to play a game of dice: one die is a fish, another a flavour, and a third, a cooking method. People can formulate a recipe putting together the three. Biswajit Das, one of its creators who imagined the project which was supported by Serendipity through the Food Matters Grant, says the project was rooted in the drying up of the Kulsi river, because of excessive sand mining, bridges built over it and weather change. “The fish started disappearing, and with it the fishermen.”

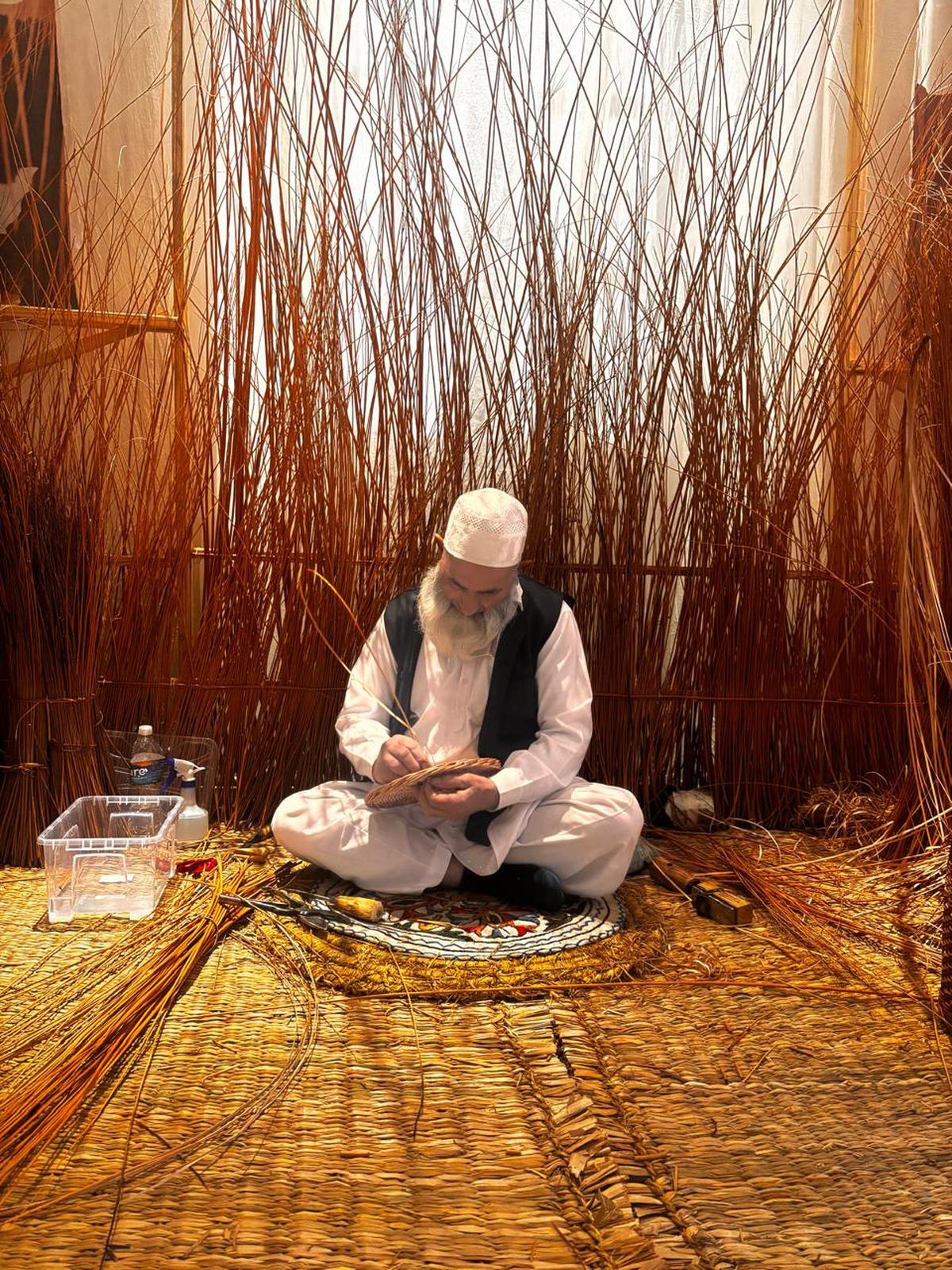

At a writing workshop on soil, a participant says, “Soil is a weighted blanket,” while another explores how it looks and feels like chocolate. Bengali and Assamese singer Shams Qabid’s song Chup (quiet) asks : ‘if you don’t say anything now, then when will you?’ A visitor speaks about how the theme of migration is running through art festivals globally. She saw it at the Venice Architecture Biennale, too. Another sits and watches a basket weaver making waguv, a Kashmiri traditional mat, which has been given a Geographical Indicator tag this year.

A Kashmiri waguv traditional mat weaver at 10th Serendipity Arts Festival.

| Photo Credit:

Sunalini Mathew

What Does Loss Taste Like? is a multi-disciplinary immersive experience about the future of food, curated by Chef Thomas Zacharias and The Locavore, a food movement, in collaboration with Immerse, an immersive-experience production company, and theatre company QTP. It presents a speculative journey into the year 2100, with cubes of food instead of food as we know it. Here, food is stripped of memory and aroma, and soil stripped of nutrients. It is about loss, the loss of soil, and with that, the loss of plant and diversity. Zacharias’ team tells participants that in that year, there will be, “One seed, one outcome. Every time!”

What Does Loss Taste Like? is curated by Chef Thomas Zacharias and The Locavore, in collaboration with Immerse and QTP.

| Photo Credit:

Chef Thomas Zacharias and The Locavore

What Does Loss Taste Like? is a multi-disciplinary immersive experience about the future of food.

| Photo Credit:

Chef Thomas Zacharias and The Locavore

Zacharias says, “After a decade of travelling through India’s food systems, sitting with farmers, fishers, cooks, and producers, and hearing the same quiet grief surface again and again, it was increasingly obvious to me that something fundamental is slipping away. I realised loss wasn’t abstract — it was deeply physical, emotional, and lived. What Does Loss Taste Like? tries to translate that into an experience, so we don’t just understand what’s disappearing, but actually feel it viscerally, and are nudged to do something about it.”

The writer was invited to the festival by Serendipity Art Foundation.

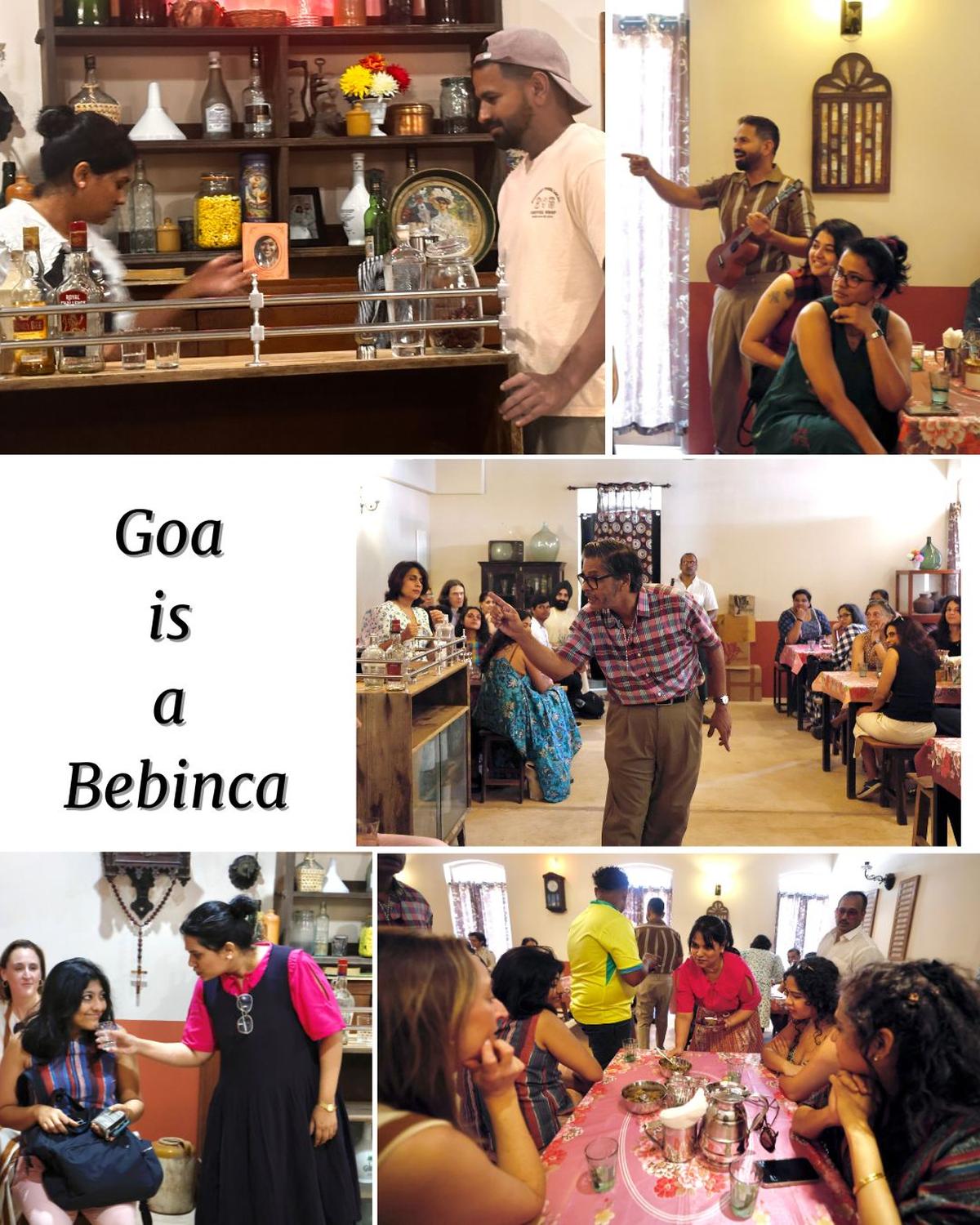

sunalini.mathew@thehindu.co.in