As India progresses steadily on its path towards becoming a global economic and political power, can we still consider English merely a vestige of colonialism in contemporary Indian society? In the ongoing debates surrounding language in modern India, it is essential to reflect on the role and significance of English in our lives today.

Beyond the discourses on Indianisation and the political advocacy for regional languages by various organisations, the role of English in India presents a compelling narrative. In modern India, English functions as a critical locomotive, without which the very notion of the nation — its identity and governance — would be challenging to conceptualise and practice. There is, however, a lack of a strong sense of ownership of the English language among its speakers in India.

Who owns English in this globalising world?

The period from the late seventeenth century to the present marks the global proliferation of English, with distinct varieties disseminating and taking on labels such as Canadian English, South African English, Australian English, and Indian English, among others. The recognition of these various “Englishes” has accelerated the study of localised forms, such as Indian English, each of which carries unique features shaped by regional influences.

Terms like ‘World Englishes’ and ‘New Englishes’ have become time-honoured to reflect the vast diversity within the language, highlighting that English does not display uniformity in terms of power, prestige, or normative standards. There are theoretical debates surrounding the standardisation and ownership of the language. In this context, there have been efforts to decolonise traditional English to legitimise its pluralistic nature and accommodate the new forms of the language emerging globally.

Question of acceptance and legitimacy

Even though India hosts the second largest English-speaking population after the United States of America, the legitimacy question of ‘Indian English’ as a global language remains unanswered. There is a lack of a strong sense of ownership of the English language among its speakers in India. While English has penetrated various domains in India — ranging from institutions to friendship, and even family interactions — there is a failure to fully recognise that English is increasingly becoming one of India’s own languages.

Linguistically, the contact of English with the Indian languages further paves the way for the ‘structural nativisation’ of English, which is known as ‘Indian English’. The problem of reckoning ‘Indian English’ as a monolithic entity or a genus of regional sub-dialects in a multilingual and multicultural context is still a vexed question.

Nevertheless, the term ‘Indian English’ has customarily been used in academic discourse to describe the linguistic outcomes after the arrival of English to the Indian subcontinent. In the absence of comprehensive theorisations, labels that describe English in India have emerged based on convenience in both media and academic circles.

These labels are, on the one hand, potential linguistic contributions of India to the development of English as a global language. On the other hand, comes ambiguity regarding the qualitative features of English in India. This ambiguity can be mitigated through the active ownership of English by Indian speakers, coupled with more theoretical exploration in the field of study.

It is essential to define and differentiate seemingly similar but potentially distinct linguistic nomenclatures such as English in India, English of India, ‘Indians’ English’, ‘Indian English’ and ‘Indian Englishes’ in a linear order. English of India implies a sense of belonging or integration of English into the existing linguistic mosaic of India and its speakers. Both these do not exclusively refer to the linguistic characteristics of English spoken in India but may indicate the initiation of a developmental pathway toward the emergence of a stable linguistic entity in its own right.

Indians’ English denotes ownership of the variety of English by Indians with increased range and depth of English within the social lives of the speakers. The development of Indian English and Indian Englishes can be understood as conjoint social processes, each influencing the other. The former can be conceived as the linguistic outcome of the above three phases of the development of the English language in India. ‘Indian Englishes’ could mean the proliferation of the established variety into various sub dialects, both regional and social.

Why is it difficult for Indians to own English as one of their languages?

One of the major hurdles that restrict Indians from fully embracing English by Indians is the premature academic push for its standardisation of English in India. Instead of supporting and advancing research into the history of language and politics of linguistic identities, Indian academia concentrated more on establishing Indian English as an independent variety without sufficient supporting data from India’s rich linguistic landscape to support such claims.

This rush to standardise the language has, in many ways, caused damage to the qualitative aspects of English in India, particularly when the history of English in India did not get the attention it deserved. For instance, many English teachers in India remain unaware that the first English school outside England was founded in Chennai in 1715. It was the St. George’s Anglo- Indian Higher Secondary School. Though these schools were built in a colonial context, their impact on inducing changes in the socio-economic and cultural setting in colonial India is tremendous yet under-researched.

Similarly, a significant section of academic energy has been devoted to investigating the role of English as a ‘killer language’ with respect to its perceived threat to local and regional languages and cultures. While such studies are undoubtedly important, particularly for efforts to protect indigenous languages, they often overlook the dynamics of regional politics manifested through anti-English narratives in various parts of India.

Historically, English in India has functioned also as a saviour language on many occasions including national liberation. Many of India’s prominent leaders, including Mahatma Gandhi, B.R. Ambedkar, and Jawaharlal Nehru, were educated in English and their vision about India’s swaraj, the framing of the Constitution, and governance of the country was their English-language education which in turn was vital for a new state and society like India.

English in contemporary India continues to be a ‘saviour language’ for individuals and communities fighting for justice, freedom, rights and equality. Contemporary movements based on gender, caste, and environment often rely on English to make their voices heard, demand justice, and mobilise public support. For instance, in transnational movements like #MeToo, social media has become a critical platform for marginalised sections of society and affected individuals to express themselves to a wider audience and establish national and transnational solidarity.

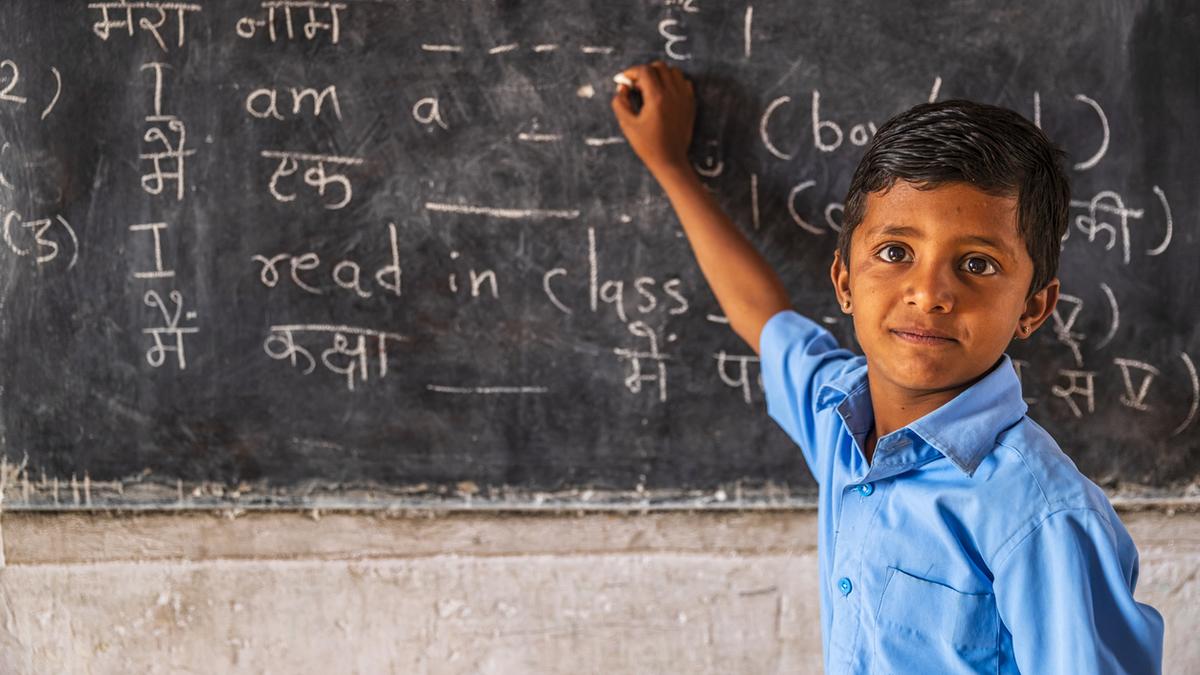

The reach of such movements is vastly different when one prefers English to regional languages. In a context like India, an educated variety of English is forceful in metropolitan and urban areas, particularly among higher-status social groups, while rural areas often remain at a disadvantage due to limited access to quality English education.

Additionally, the rural-urban divide poses a considerable threat to the democratic opportunity for English language learning in India. Innovations in Information Communication Technology (ICTs) should be employed at various levels to address the rural-urban divide ensuring that rural populations also have opportunities to learn and benefit from English language education.

In contemporary cities, one is faced with two main language contact possibilities; the ‘salad bowl’ and the ‘melting pot’ models. In a salad bowl situation, the languages are continuously in contact with each other due to the cultural harmony co-existence in the linguistic landscape. In contrast, the melting pot metaphor suggests the dominance of one language or culture within a linguistically plural landscape.

Since linguistic identities are constructed by the overlapping of socio-cultural and politico-economic factors and their outcomes, and as such, government interventions are necessary — not to categorise English as a foreign-external language, but to embrace and integrate it for the future of generations to come.

Traditionally, the variety of a language considered “standard” is the one spoken by the dominant socio-political group in a society. While this may hold for languages like Hindi, English’s journey toward becoming a linguistic hegemon in India is still ongoing and distant.

Rather, careful planning and intervention at both political and academic levels are required to cultivate English alongside regional languages, positioning it as a “friendly language” that fulfills functions other languages cannot. Beyond its role as a lingua franca, English in contemporary India is increasingly permeating intimate domains. However, this does not imply that English is replacing regional or mother tongues for most Indians.

The growing presence of English in everyday life underlines its evolving role, but it is important to recognise that it does not diminish the value of other languages. Academic communities can play a vital role here by incorporating into curricula the history and trajectory of the growth of English in India, with a significant emphasis on the importance of linguistic harmony and the coexistence of languages in their respective functional domains.

English is no longer merely a colonial or Western language. It is now sustained and shaped by speakers in the non-Western world, including India. For future generations, English will undoubtedly remain an essential tool for socio-economic mobility.

Let’s train our students to preserve their linguistic and cultural identities without categorising English as an external language, but become global citizens with good command in English, by recognizing the purpose and roles of languages. Therefore, it is time to embrace English as one of our own languages — one with an enriching past and a promising future. Furthermore, for English to be considered legitimately global, non-Western affiliations like India’s ownership is a crucial aspect.

(Dr. Elizabeth Eldho is a Visiting Assistant Professor of English at the Indian Institute of Petroleum and Energy, Visakhapatnam.)

(Please email us your suggestions and feedback regarding education to education@thehindu.co.in)

Published – March 19, 2025 04:47 pm IST