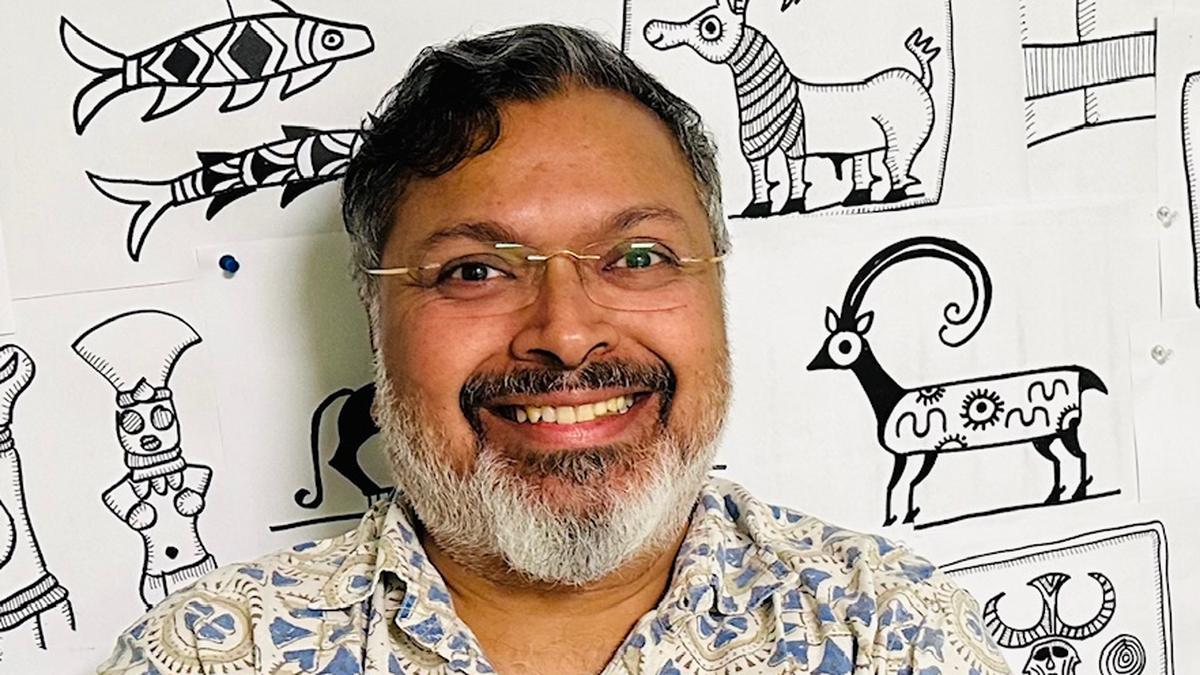

A century after the world learned of the existence of the Harappan civilisation, as ancient as Mesopotamia and Egypt, Devdutt Pattanaik reflects on the “peculiar” but peaceful Harappans in his new book, Ahimsa, which he has also illustrated. Edited excerpts from an interview.

You’ve dedicated ‘Ahimsa’ to ‘those who choose dialogue (sam-vaad) over debate (vi-vaad)’. Was this inspired by your experiences on Twitter?

More than Twitter, that’s a silly space, it was academia. The way the academy is designed is through argument and debate. When someone does their PhD, we say ‘defend your thesis’, it’s very combative. The academy comes from the idea that there is one truth — this works in science because, at the end of the day, you have to get mathematical, objective evidence. In the realm of history, to a large degree, you can get it, but when it comes to more subjective things like art, mythology, ideas, it becomes extremely difficult to figure out what’s going on. I say: don’t argue, listen. Try to figure out different ways in which we can understand the same thing.

Miniature votive images or toys from Harappa, c. 2500 BCE, clay figurines of zebu oxen, a cart, and a chicken.

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

A general view of Dholavira Harappan site at Dholavira, Kadir, Kutch.

| Photo Credit:

Vijay Soneji

You list the prejudices historians might bring to the study of Harappa. E.H. Carr once wrote that all historians have bees in their bonnets, you have to listen to the buzzing. Do you have any bees of your own?

I do. I don’t like this notion of triumph or the greatness of the past. I don’t see the past as better or worse than the present. A discourse in which the past was great or the past was terrible, both bother me a lot, and my instinct is to counter it, to see if there is an alternate way of looking at the same thing. There are good people, bad people, difficult lives, good lives. Technology keeps changing but emotionally, do we really change? You’ll see that sense in my writing a lot.

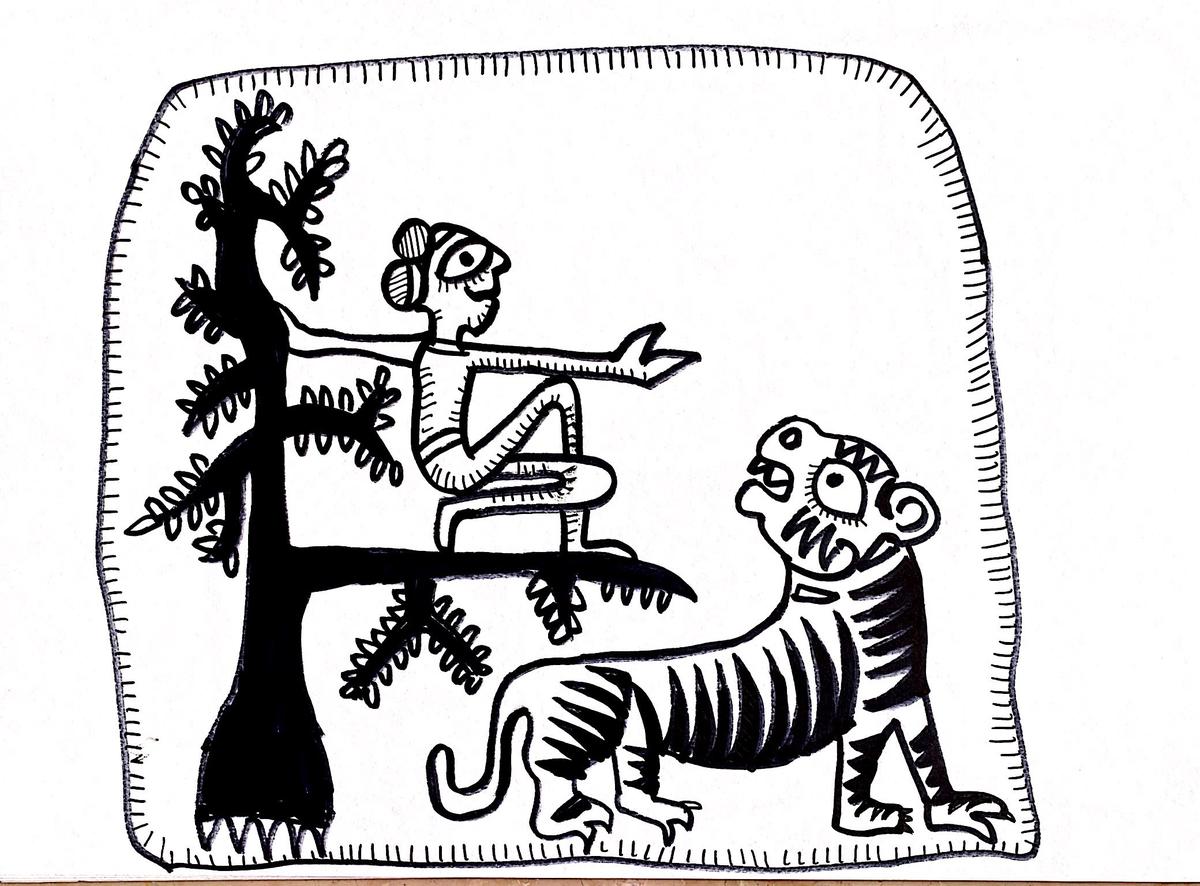

A worshipper is often shown making offerings to a tree or a deity in Harappan art. In this illustration, a worshipper sits in a half-kneeling position calling out to a tiger.

| Photo Credit:

Devdutt Pattanaik

Stamp seals and impressions, some of them with Indus script; probably made of steatite; British Museum (London)

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

Why did you choose Harappa?

I was interested in the art. Some of the art in my book was done years ago in a fit of inspiration. I kept sketching the bull, the unicorn, the rhinoceros, the crocodile [from the Harappan seals]. As I was drawing, I noticed that the animals are anatomically absolutely correct, almost like photographs — it’s quite impressive. I went down a rabbit hole of information, you go in deeper and deeper and your head starts to spin. I’m not a historian — I’m not interested in the history, I’m interested in the mythology of that period, how they imagined the world.

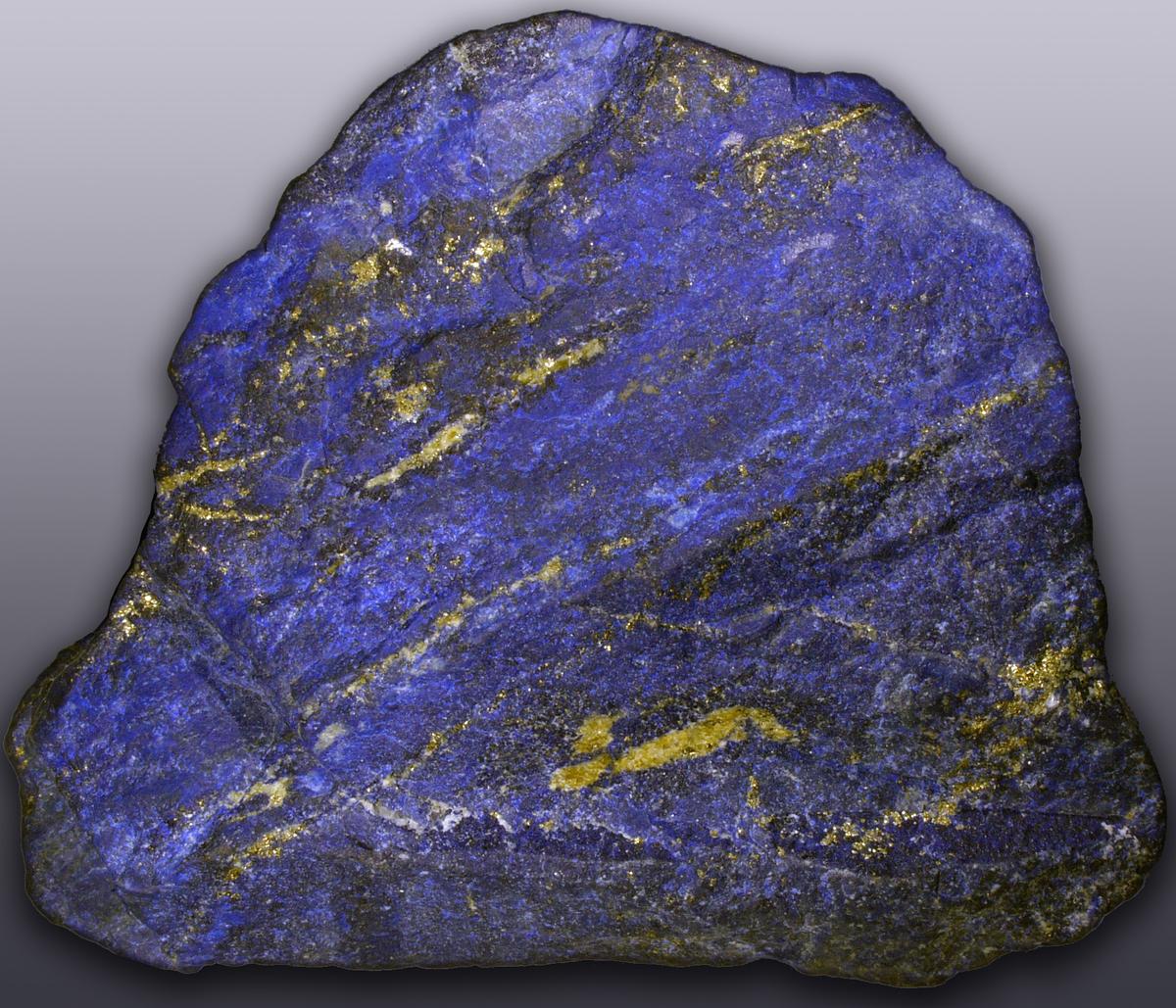

Lapis lazuli

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

The timelines [are fascinating]: the pyramids are built exactly when the Harappan cities are being built. The lapis lazuli — a stone found only in Afghanistan — made its way to Mesopotamia along the sea coast from Harappa. It’s something every child in India should know, but we don’t talk about this — 4,000 kilometres, 4,000 years ago at the time of the pyramids, by a culture that has no big monuments, does not seem to glamourise violence and power. This is a very peculiar civilisation.

Ruins of Harappan city Dholavira in Rann of Kutch, Gujarat.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/iStock

Your broad interpretation of the civilisation is ‘ahimsa’ – of peace deriving from a mercantile ethic. But there is also a thread on the ‘resistance’ to this regulated society. How did these contrasts play out in your mind?

There is definitely a lot of standardisation, clearly there is institutional control, but there are also regional differences, and that caught my eye. Punjab is very different from Sindh, which is very different from Gujarat or Haryana. The climate is different, the animals and crops are different. This whole ecosystem was very different from the drab ‘city state’ [idea of Harappa] that has been amplified. All that excited me.

I noticed when I started my study of mythology that we glamourise kings and the priestly class but we never talk about merchants. The Ramayana and Mahabharata do not talk of trade at all. The Jatakas talk a lot about trade, and the Jatakas are the mercantile and monastic traditions coming together. My thesis was — if the Jains are traders and they are following ahimsa and talking about monasticism, and if Harappa was also a trading society, and they established these institutions without violence, the only logical thing is that there is some kind of a narrative, some ideological control that is happening, probably through monks, or some quasi-monastic order.

‘Dancing Girl’

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

Why are more people not fascinated by Harappa the way you are? Why do the Aryans get more interest?

The Aryans have been a ‘cool’ thing for over 200 years. Harappa is relatively boring. Other than toilets and organised cities — which Indians never valued. I’ve been to Lothal and I was very impressed by the standardisation and the geometry, but it’s boring! It doesn’t have the mystery of ancient Egypt, with all its mummies and these grand buildings that intimidate you. The seals are tiny. The first time I saw the famous dancing girl [in the National Museum] I was a little heartbroken because I realised it was only 10 cm tall. I genuinely believed it was a big statue. We are spoiled — we have these grand temples, we’ve got Nizamuddin and Thanjavur, in front of this Harappa just doesn’t [match up]. And there is no story, nothing to connect us.

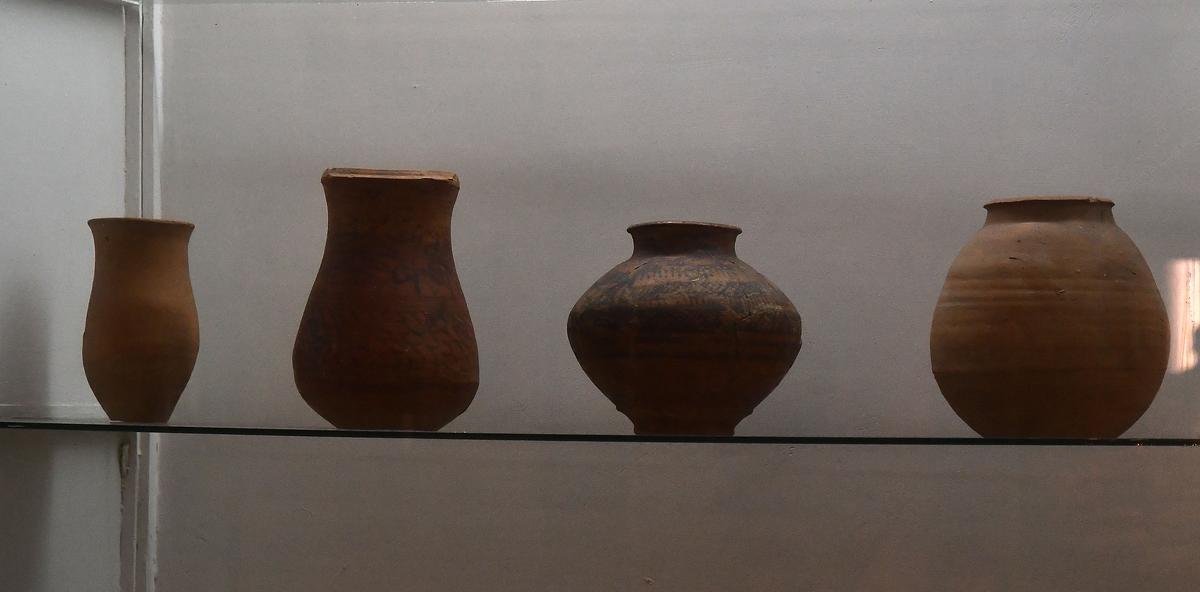

A view of different types of miniature clay pots unearthed from Dholavira, kept at the National Museum, New Delhi.

| Photo Credit:

Shiv Kumar Pushpakar

We want to find all our truths in the ancient past, yet here we have something ancient but it isn’t exciting to our imagination.

The History Channel didn’t make any money until it started talking about aliens and conspiracy theories. Historians puncture your vision of the world, telling you something very boring. And politicians look at the past as a way of not dealing with present issues. The National Museum once said they would serve Harappan cuisine and then they decided not to serve non-vegetarian food because it doesn’t fit into the narrative. And I’m like: you’re not interested in the past, you’re interested in some fantasy.

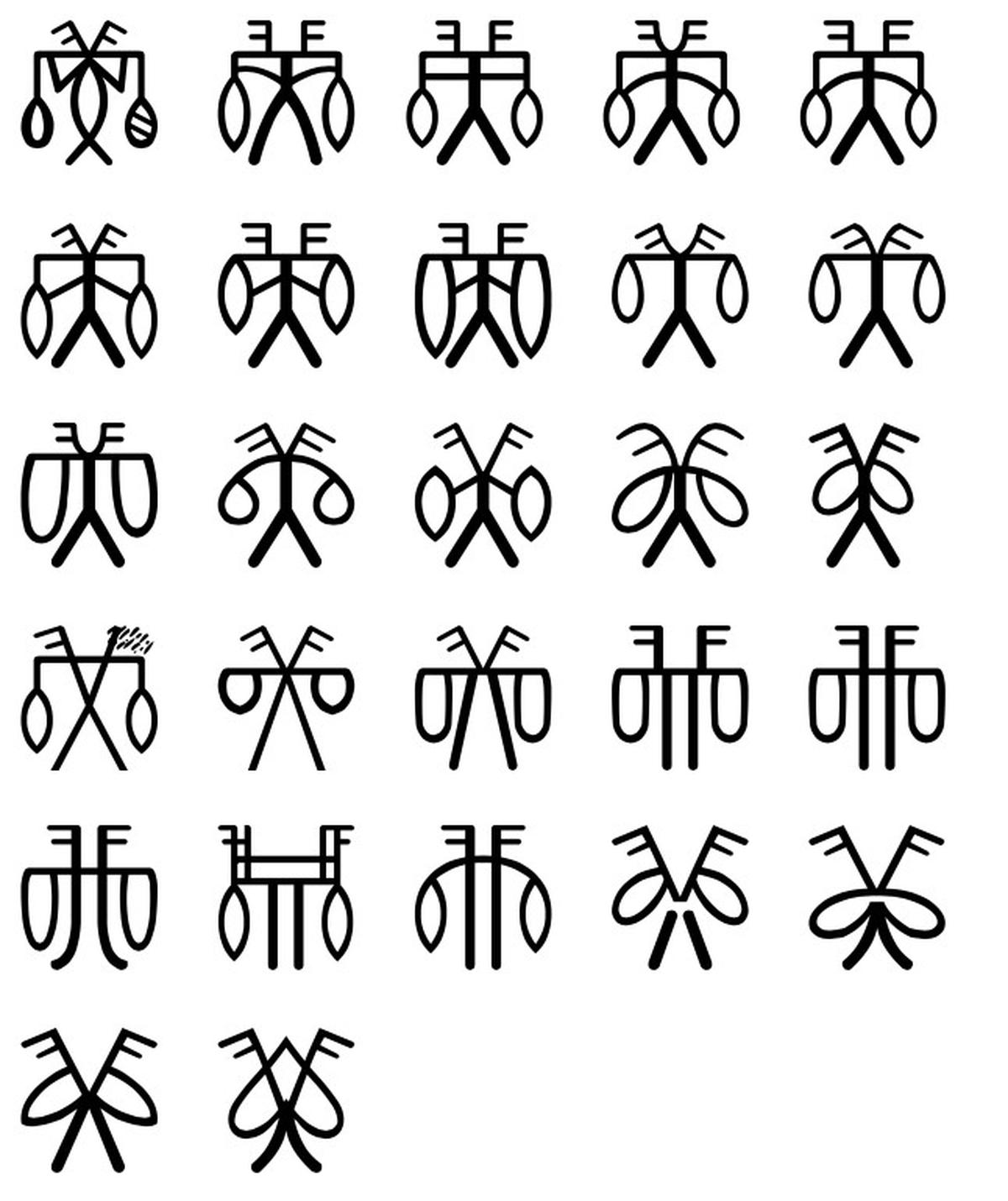

Harappan script

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

Imagination is one way of accessing the past, and imagination of the past is tied to imagination of the future. Was there a future for India that you imagined while you imagined the Harappan past?

I was seeing the narrowness in [our] thinking. For example, everyone talks of the Harappan script and there is this yearning to see it as a language with sounds so I can read it, and typically they will find Sanskrit words and Vedic verses… but why does it have to be sound? I started reading papers by scholars and there is massive work going on, they’ve seen patterns in how the symbols appear, how it probably isn’t a sound-based script, it’s probably emoji-like. This is the lateral thinking that people have brought to the table, and I think this lateral-ness is missing in modern discourse.

How do traders work? Traders have to deal with different cultures, markets, people, but they find ways of negotiation. Is it possible the Harappan merchants figured this out — you know what, we need stones from one part of the world, wood from another, we need seashells, fabric, bitumen and we have to work with different people and we can’t homogenise these things. That’s why ahimsa became important. This whole idea of ahimsa being reduced to vegetarianism and to Gandhian philosophy… it’s a very narrow way of looking at ahimsa, not looking at it from a mercantile point of view.

Pashupati seal

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

The fact that the Harappans used wild, male animals in their emblems indicates an understanding of power, autonomy, aggression — yet working together. The Pashupati seal has these animals on it. These are clan animals brought together by a mystical figure. Which reminded me of how India functions: we have ‘wild animals’ being told you have to work together for the good of the country. But rather than looking for that, we’re looking for fantasy.

But this [other way of looking] is useful, it’s helping me think about present issues, which makes the past relevant. Otherwise what’s the point of knowing the past? It’s not for the ego, it’s to make me a better person today.

Ahimsa; Devdutt Pattanaik, HarperCollins, ₹499.

The interviewer is the author of ‘Akbar of Hindustan’ and ‘Jahangir: An Intimate Portrait of a Great Mughal’.

Published – January 24, 2025 09:05 am IST