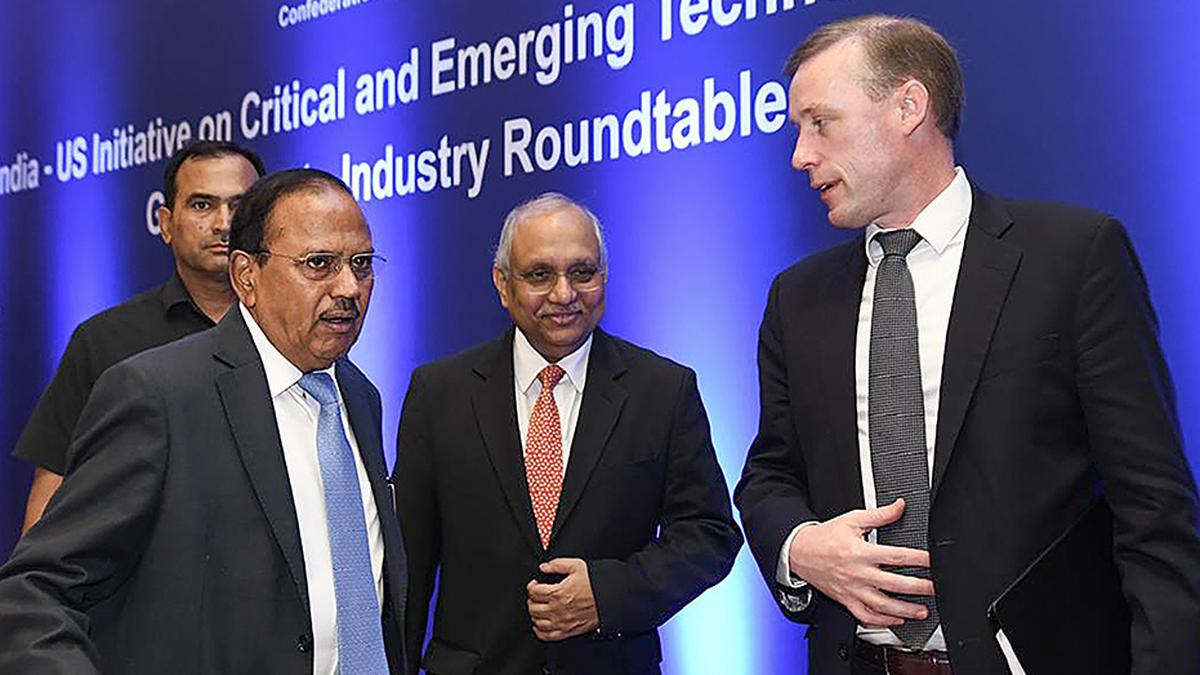

National Security Adviser Ajit Doval, CII Director-General Chandrajit Banerjee (centre) and U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan (right) at the exclusive Industry Roundtable on India–U.S. Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies in New Delhi on June 18, 2024. Photo: Handout via PTI

Despite the seemingly successful talks between National Security Adviser Ajit Doval and his U.S. counterpart Jake Sullivan in June, to make progress on the bilateral Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies (iCET), structural challenges endure in its execution.

Local industry officials and military analysts maintain that these impediments pertain primarily to the autonomy of U.S. defence companies with regard to transferring technology, which have been developed at immense cost at Washington’s behest with many companies zealously guarding their intellectual property rights (IPR) over it. Additionally, the U.S.’s strict export control laws in this regard, controlled by its defence industrial complex, were loath to sharing military technologies via joint ventures, however meaningful they might be to Washington’s wider strategic interests.

For now, the iCET’s defence component is focused on India locally manufacturing General Electric GE F-414INS6 after burning turbofan engines to power the under-development Tejas Mk-II light combat aircraft and locally assembling 31 armed MQ-9 armed Reaper/ Predator-B unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), under acquisition for all three services, for around $3 billion.

Limitations

Official sources claimed negotiations had been concluded for GE to transfer around 80% technology to Hindustan Aeronautics Limited to produce the F-414 engines, but not critical know-how related to forging metallurgy discs for the power packs turbines. Technology transfer from General Atomics Aeronautical Systems to assemble the MQ-9s reportedly stands at around 10-15%, and includes establishing a domestic maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) facility for the UAVs. Alongside, directly acquiring, licence-building and co-developing the General Dynamics Land Systems Stryker Infantry Combat Vehicle for the Indian Army, under iCET patronage, is under negotiation.

But innate limitations in all these ventures persist.

Military analyst Abhijit Singh said that the U.S. government does not presume to act on behalf of its defence companies that own the IPRs for their sundry wares. Besides, U.S. defence vendors, he cautioned, were answerable to their shareholders, whose motivations were largely commercially driven. This, in turn, could adversely impact the quantum of technology they were willing to transfer.

It was precisely these mercantile considerations, weighed down by cumbersome bureaucracies, that led to the failure of the 2012 Defence Technology and Trade Initiative (DTTI) between India and the U.S., and on whose ashes the iCET emerged in June 2023, albeit with a more ambitious remit.

The DTTI flopped due to technology transfer issues. The iCET emerged enabled, in turn, by an alphabet soup of organisations including INDUS-X (India-U.S. Defense Acceleration Ecosystem), Joint IMPACT (INDUS-X Mutual Promotion Advanced Collaborative Technologies) 1.0, IMPACT 2.0 and ADDD (Advanced Domains Defense Dialogue).

Exercising ‘jugaad’

Meanwhile, a cross-section of domestic defence industry officials averred that one strategy to ensure iCETs attainment, and that of related projects, centred on the U.S. permitting the Indian military to exercise the jugaad or innovative option on its U.S. platforms such as attack and heavy-lift helicopters, heavy transport aircraft, and naval surveillance aircraft it had acquired. After all, this resourceful jugaad recourse had provided India’s military with user flexibility, by ably rendering imported platforms serviceable in climatic extremes and assorted terrain. Through trial and error over decades, the services had elevated jugaad to sophisticated levels to ensure that foreign weapon systems performed over their declared potential. For instance, jugaad had rendered the fleet of Chetak’s and Cheetah’s, principally French-origin Alouette III’s and SA-315B Lama’s, capable of operating to heights over 14,000 feet in the Siachen glacier region, a feat their original equipment manufacturers had never deemed possible.

But the complex set of ‘enabling’ protocols that India had executed with the U.S. ahead of acquiring all the aforementioned assets simply foreclosed the possibility of pursuing the established, and at times, essential jugaad route. Besides, most of these acquisitions effected via the Foreign Military Sales or FMS route were concluded under the stricter ‘Golden Sentry’ end-use monitoring programme which completely disallows jugaad.

The iCET also appears to be part of the U.S.’s overall policy, outlined in a recent Senate Foreign Relations Committee report, which urged President Joseph Biden to address the ticklish issue of India’s close strategic ties with Moscow and particularly its dependency on Russian arms. The implicit suggestion in the February 2023 report was that India should now begin sourcing its future military kit from Washington, conceivably via the iCET route.

Hopefully, the iCET will not fall prey to Augustine’s Laws, the tongue-in-cheek aphorisms immortalised by Norman Augustine, an Under Secretary of the U.S. Army. One Law states that the more time both sides spend talking about what they had been doing, the less time they had to spend doing what they were talking about. And eventually they (could) end up spending more and more time talking about less and less, until finally they spent all their time talking about nothing.

Rahul Bedi writes on defence and security issues