The 2024 general election verdict has many takeaways. While some say that it has enlarged what was becoming a shrinking space for dissent and democracy, others say it has created hope for change in the future by reining in what would be called Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s virtual dictatorial run.

But these are only the visible effects.

There is something deeply philosophical about this verdict. It is actually a civilisation-strikes-back occasion for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its ecosystem. The Hindutva project, that is spearheaded by Mr. Modi, has re-opened the old civilisational suspicion in the minds of the religious have-nots among Hindus. Far from creating a Hindu monolith, it has resulted in only counter-polarisation among Hindus themselves.

Clearly, Hindutva’s civilisational call to Hindus to unite against a perceived enemy, mainly Muslims and liberals, and to reclaim Bharat’s “glorious” past has proved counter productive. The 2024 verdict has proved that Hindutva politics has ended up polarising Hindus instead of uniting them.

The Constitution as turning point

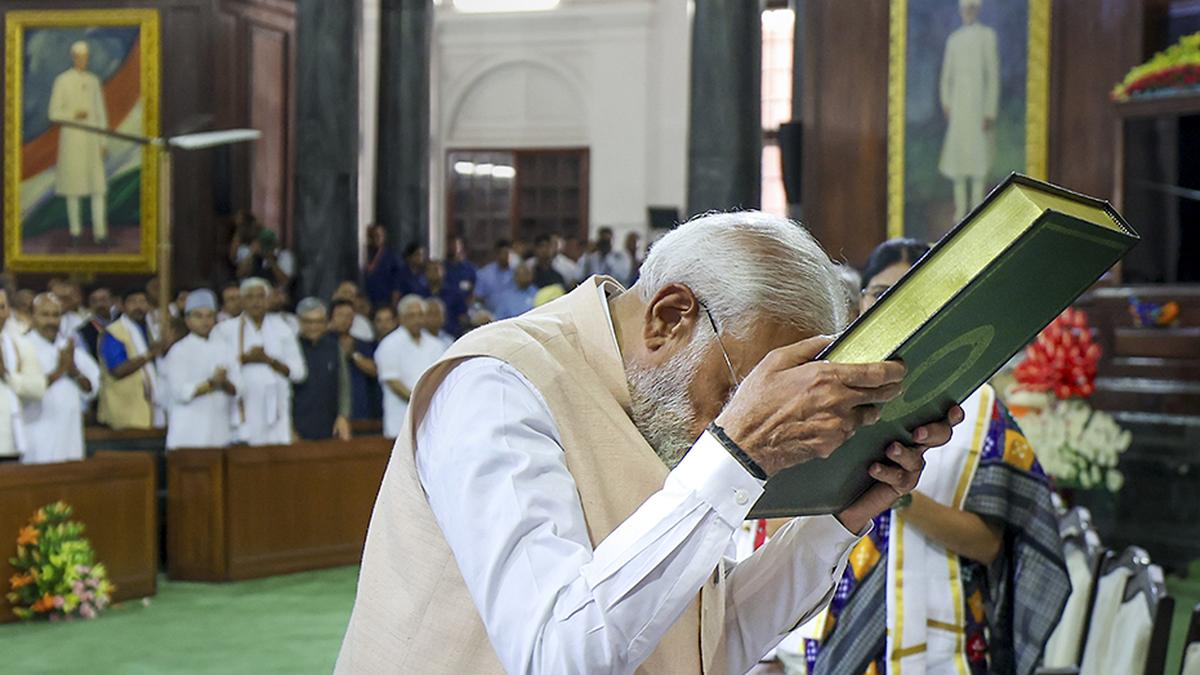

This has been amply borne out by the subject of the Constitution gaining huge currency in the 2024 battle. The Constitution has been under attack from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh ecosystem right from the time it was being formulated and debated. With Mr. Modi riding a wave of unprecedented popularity, the Hindutva ecosystem thought it had the numbers in Parliament and also sufficient moral authority to start talking about “changing the Constitution”.

It began by blaming the Opposition for orchestrating a ‘false’ campaign against the BJP that it would change the Constitution to rob the backward castes and tribes of their affirmative action privileges guaranteed by the statute. But the Opposition was only picking up points from the several statements made by the BJP’s own leaders and poll nominees.

Mr. Modi also entered the election with a repeated and strident call for 400 seats for his party. A relevant question was why was this number needed if not for changing the Constitution?

When some questions began to be asked, Mr. Modi tried every trick to neutralise any perception over the issue of the Constitution. But the impression had percolated deep and the damage had been done.

The most encouraging takeaway from this battle between Hindutva’s civilisational haves and have-nots is that the Constitution — which embodied the essence of the civilisational course correction painstakingly championed by the leading lights of Independence struggle — itself proved to be the reason for this realisation about the real intent of Hindutva’s civilisational project. This was to resurrect the so-called great and glorious past of Hindu civilisation and to “decolonise” Hindu society’s collective mindset through a project that essentially relied on poisoning people’s minds with a pathological hatred for those who do not belong to Hindu civilisation.

The Constitution itself was necessitated by the deeply dehumanising inequalities inherent to Hindu civilisation. In fact, Constitutions all over the world were necessitated by similar concerns.

Right-wing intellectuals, however, very insidiously try to belittle the path-breaking contribution by the makers of modern India by arguing that the statute book has great values in it not because of any outside influence, but because those values have flowed in from the “great” Hindu value-system.

One of the most commonly cited examples of this argument is that secularism was always inherent to the Hindu way of thinking. And, as such, it found its expression in the constitutional scheme of things.

The Hindutva protagonists, however, in the same breath, also prove themselves wrong by indulging in a demonising of Muslims and other minorities.

This hatred for non-Hindus is not the only thing that contradicts their own claims of “justness” in Hindus’ ancient civilisational past. It is the affirmative action part of the Constitution that Hindutva revivalists often find tough to sit pretty with. So, while overtly supporting reservations, many Hindutva protagonists often openly denigrate it and also form the vanguard of “save merit” campaigns.

It also shows up when they start glorifying the Manusmriti and also try to introduce it in school and university curricula.

Clearly, their line of the Constitution being a reflection of past glory is subterfuge to cover up their ideological forefathers’ past sins of opposing the Constitution in Constituent Assembly debates as well as in articles in right-wing publications when the Constitution was in the making. But the cover-up has been exposed.

‘Political acumen’ that was overestimated

The Hindu have-nots have a clear sense now of the possibility of the BJP turning the Constitution on its head by altering it to suit the BJP’s idea of India that is anchored in some deeply problematic sociological premises. This realisation has had its singlemost profound impact in the 2024 elections — in a humiliating reversal for Mr. Modi’s mission. And, as it is there for all to see, the BJP has only itself to blame. The Opposition only found the weak spot and exploited it to stunning effect.

What Mr. Modi and the whole Hindutva ecosystem must understand is that their social engineering and Hindu consolidation efforts over the past many decades have been brought to a naught by themselves alone. They tried to stand on two stools — an anti-minority plank and Constitution misdemeanour — and only ended up falling between the two. They tried to unite caste Hindus (upper castes were always organically on board) against Muslims and also antagonised caste Hindus, who were their foot soldiers in the anti-Muslim project, with their anti-Constitution bravado. In the process, they paid a heavy price.

There are several examples that underline this boomerang effect in this election. But nothing illustrates the issue in this way than the BJP’s own defeat in Ayodhya in this election. The fact that the Opposition candidate, a Dalit candidate fielded by the Samajwadi Party, won shows that the people were not receptive to the Ram temple as something with which to cover themselves in glory, and that social justice was the real public concern. It also exposed the overestimated political acumen as well as the vulnerabilities of the BJP’s self-styled Chanakyas.

So, where does the Hindutva project, in decline, go from here? Will this suspicion in the minds of the Hindu have-nots remain etched or will it wither away with time?

Going a bit deeper into the subaltern side of this election, it looks that the advantage of the BJP’s labharthi (beneficiary schemes) was mostly cancelled out by the Samvidhan (Constitution) buzz since the labharthi section is largely the same as those disturbed by the BJP’s Samvidhan plan. With this, the BJP’s best bet becomes ineffective.

The Opposition must rediscover its voice

With Mr. Modi now having to run a coalition government, the Constitution debate might remain latent, unless the Opposition keeps it burning.

And burn it must, because a vast majority of Hindus have been fooled into believing that their real battle is with Muslims and not with the Hindutva haves, when actually, if at all, it is the other way round.

The makers of the Constitution had such deep divisions within India, and Hindu society in particular, in mind when the Constitution was being drafted. The non-BJP regimes managed to keep the Constitution’s basic structure intact, keeping not only Hindus and non-Hindus together but also a deeply divided Hindu society as one whole.

Now, the Constitution has struck back, giving the BJP a civilisation rebuff.

The Opposition has its task cut out. It must keep this fight of social justice alive and prevent the misuse of Hindu have-nots to achieve Hindutva’s communal goals.

The Hindu have-nots must cease to be a part of the right-wing’s project as they have their own battles to wage and win against those who have misled them into believing that their real battle lies outside the Hindu fold.

Vivek Deshpande, now a freelance journalist based in Nagpur, was with The Indian Express