Kindness is not the first trait that comes to mind when we think of James Bond, but it is telling how often this adjective is brought up in connection with his author. Nicholas Shakespeare’s biography, Ian Fleming: The Complete Man, attempts to decode the “enigma” who created one of the world’s best known fictional heroes, an English secret agent who has had a huge impact on the culture of the 20th century and onward. After all, five words — “The name’s Bond. James Bond” — are guaranteed to ignite a smile.

Nicholas Shakespeare

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

In an interview on the sidelines of the Jaipur Literature Festival, Shakespeare shed light on Fleming’s legacy, how he was an influential figure in his own right, and why Bond has endured. Edited excerpts:

Author Ian Fleming in Jamaica.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Your expansive biography of Bruce Chatwin pinned down an intrepid traveller and writer. What were your first thoughts when asked to write one of Ian Fleming?

I was wary, though the Fleming Estate promised access to family papers that had not been seen before, because I wondered whether there was anything more to learn or say about Fleming that had not been told already. But as I did a background check, I found that under the bruising surface of his popular image, there was a different person — or people — and many stories. Almost everyone, including past lovers, vouched for his kindness; most agreed that he was “many people” in one. I found that virtually anything you can say of Fleming, the opposite is true too. Also, like Chatwin, he was restless, charming, attracted to both men and women, and pursued knowledge. For instance, he was an important book collector and owned the antiquarian quarterly, The Book Collector.

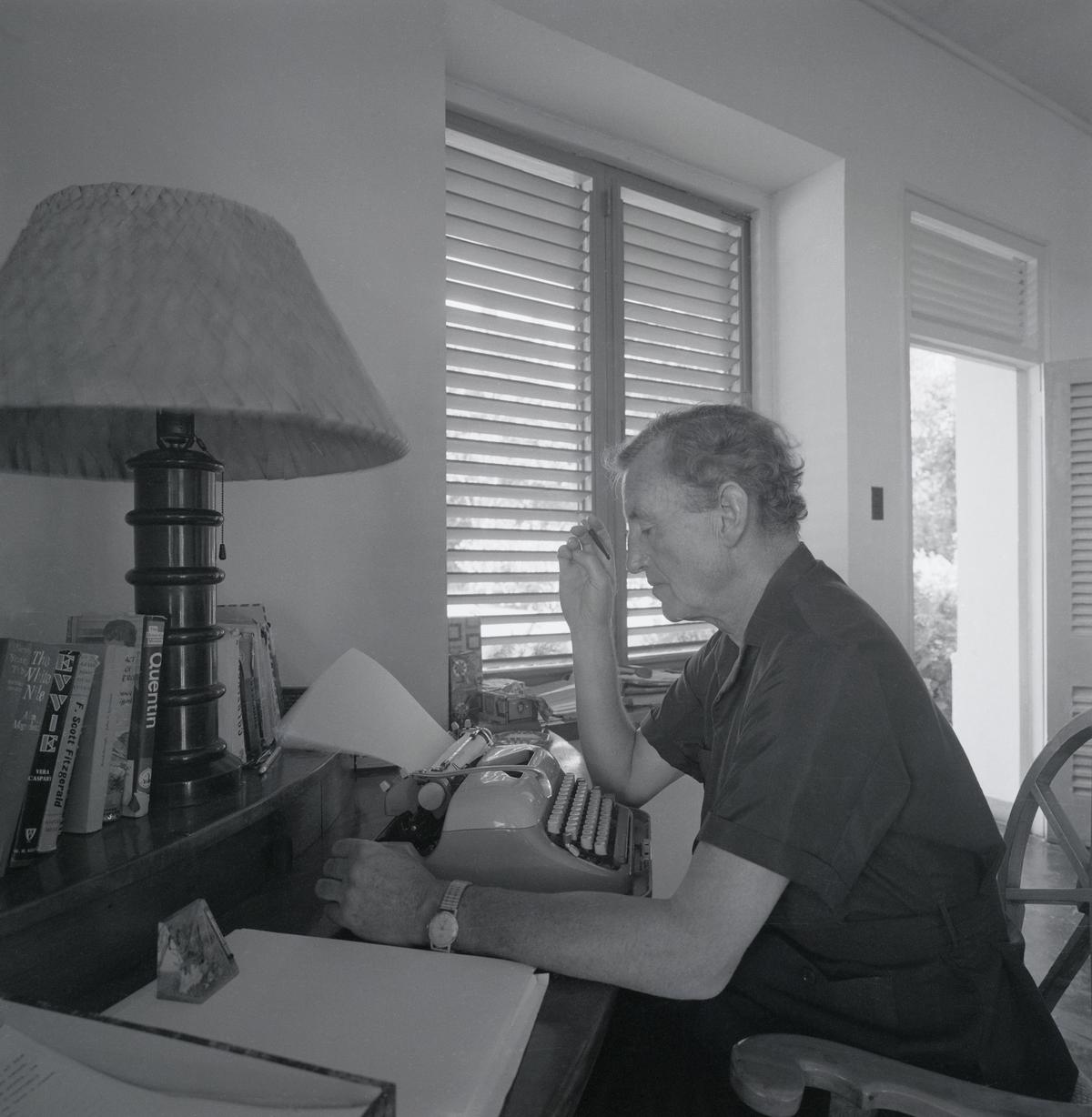

Ian Fleming at his typewriter.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

As you researched, were you surprised that there’s a huge interest in James Bond, but a lesser interest in Fleming, the creator?

Yes, it is a bit strange because Fleming was a lot more substantial than his fictional character. As Hitler was coming to power, Fleming lived in Austria, Munich and Geneva, and he made a noteworthy contribution to World War II. For example, he organised covert operations in Nazi-occupied Europe and North Africa that helped to shorten the conflict. He was also part of the inner circle of the British powers-that-be and asked to help bring the U.S. into the fight. He worked to set up and then coordinate with the foreign intelligence department that developed into the CIA [Central Intelligence Agency].

Fleming was part of important decisions but he couldn’t really write about it, could he?

No. He was an influential figure in his own right and even world leaders like John F. Kennedy consulted him. There’s a story, not apocryphal, that President Kennedy sought Fleming’s views on how to handle the Cuban crisis, and some of those ideas were indeed implemented. He had fascinating stories to tell but security concerns prevented him from writing them.

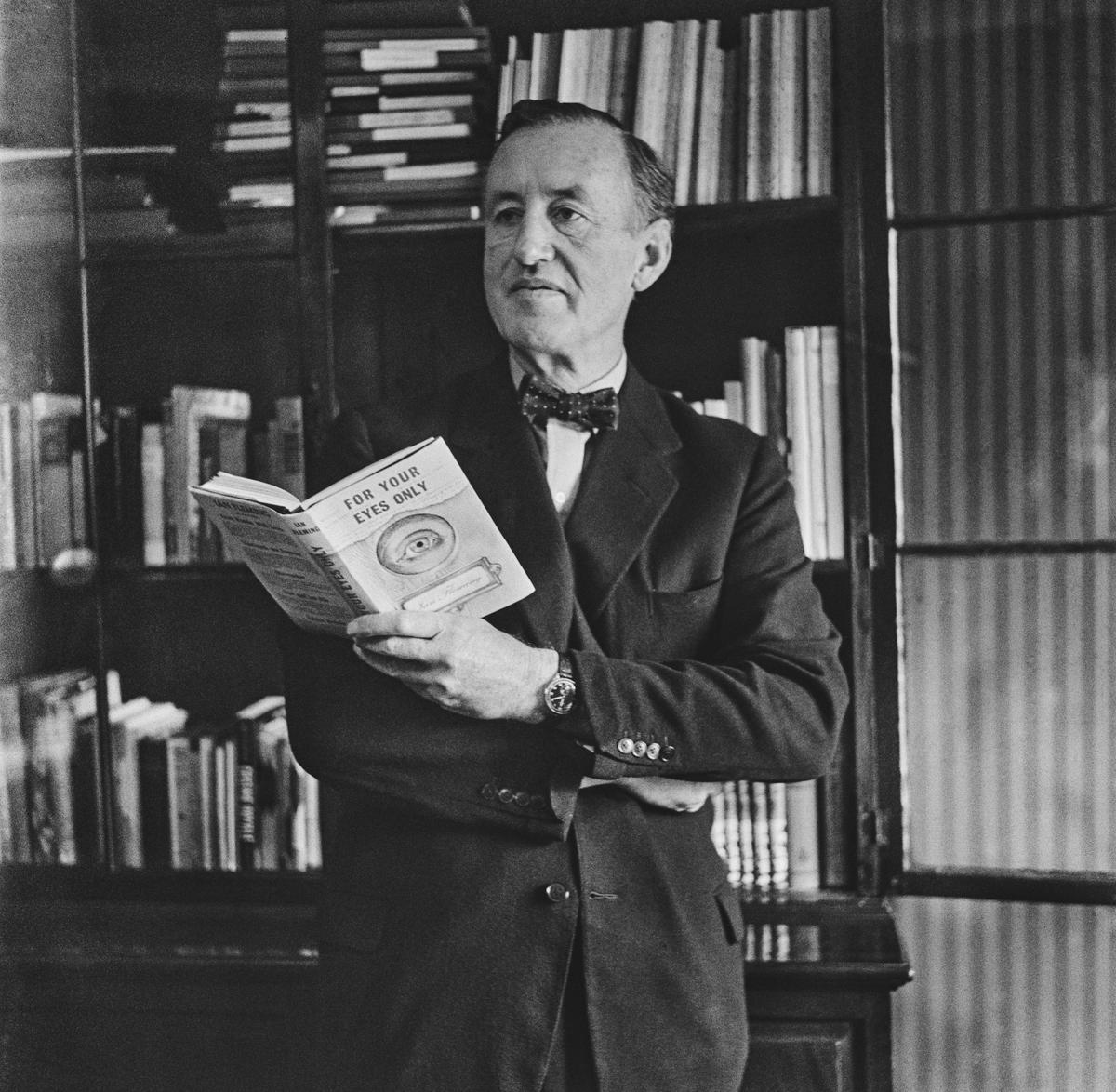

Author Ian Fleming (1908-1964) in his study, holding a copy of For Your Eyes Only, in 1960.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Is that one of the reasons he turned to fiction?

Well, he created his fictional hero in the last dozen years of his life — he died when he was only 56 years old — and almost as an afterthought. And yet, Fleming’s “fast-moving, high-living” character with his love for cars, women and Martinis, has acted as a lightning rod for generations and their understanding of politics, culture and sex. Fleming knew the undercover world intimately, and there’s a lot of Fleming’s real-life experience in Bond, but it will be fair to say that if Bond had not existed, Fleming is someone we should still want to know about.

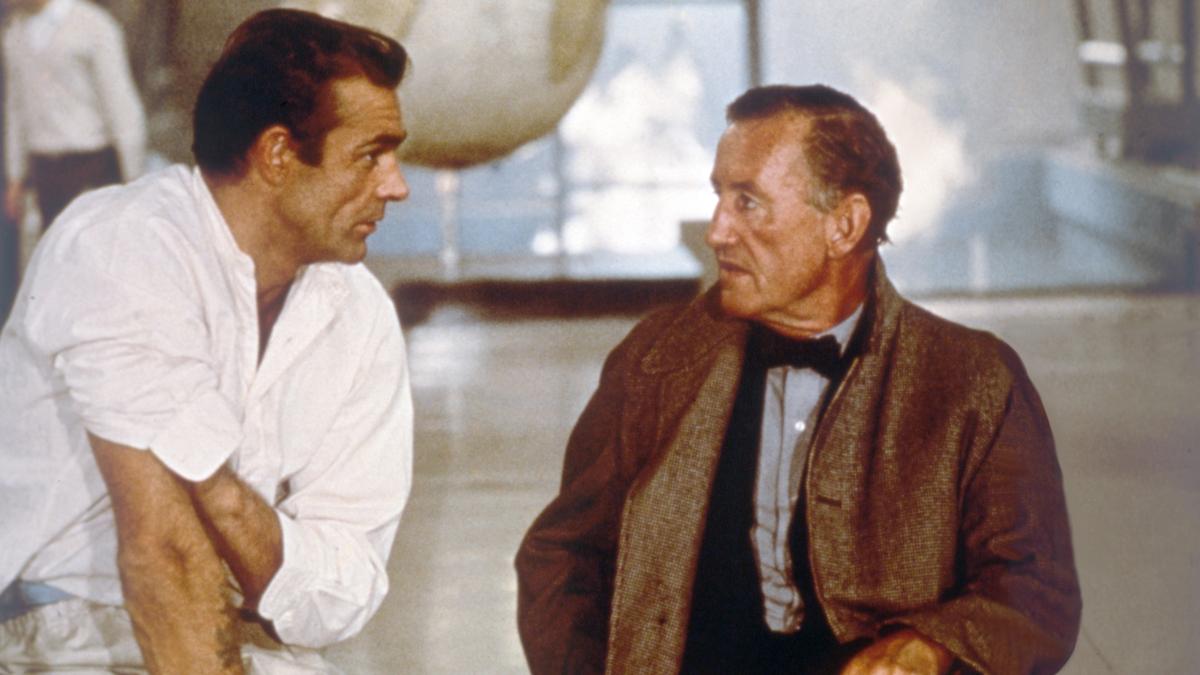

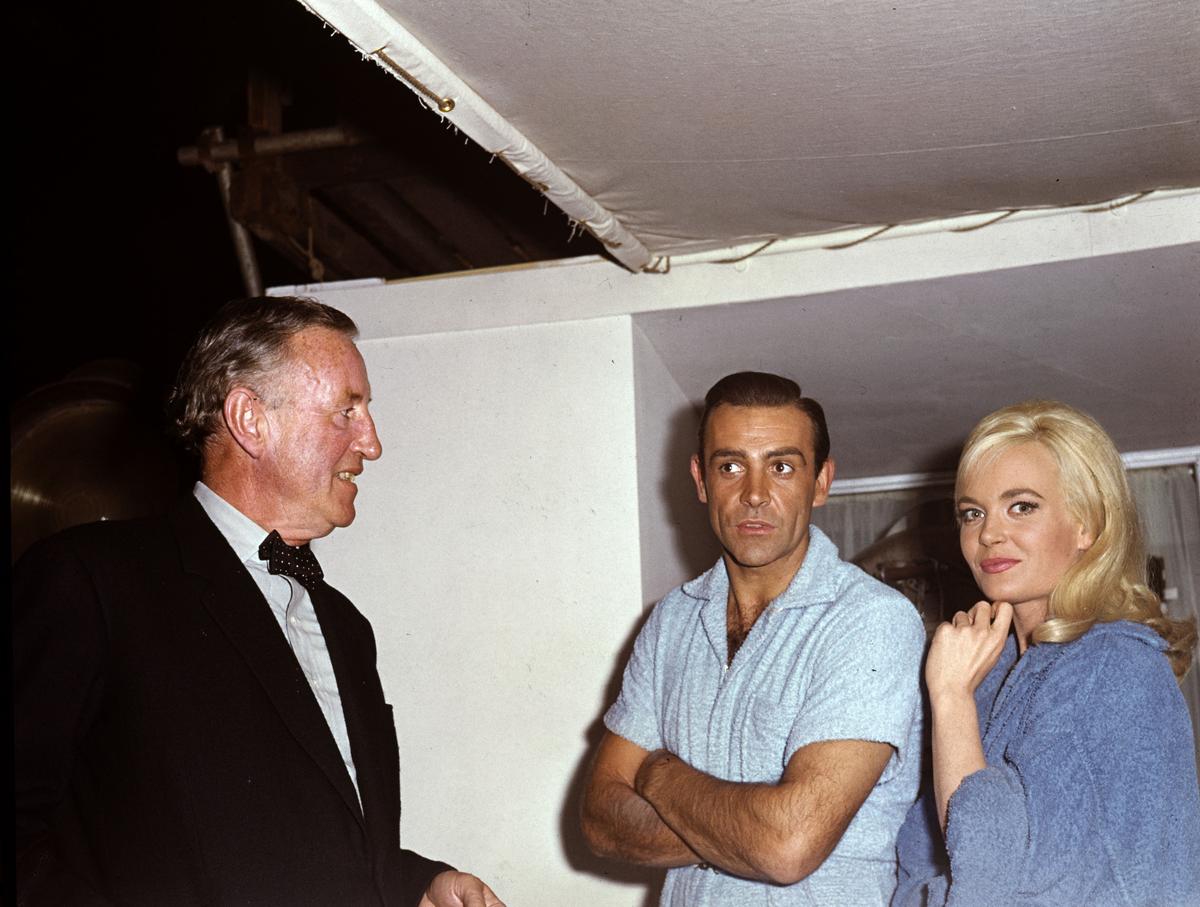

On the set of the James Bond movie Goldfinger. (From left to right) Author Ian Fleming, actor Sean Connery and actress Shirley Eaton.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Graham Greene and John le Carré also knew the world of spies…

Greene and le Carré, like James Bond, were minor players in British Intelligence, unlike Fleming, who was in the inner sanctum of British covert operations. Ian, and his brother Peter, were part of a select group cleared to know the war’s top secrets, the decrypts from the code-cracking centre at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire: in April 1940, the list of those with access to this information, known as ULTRA, was restricted to less than 30 people.

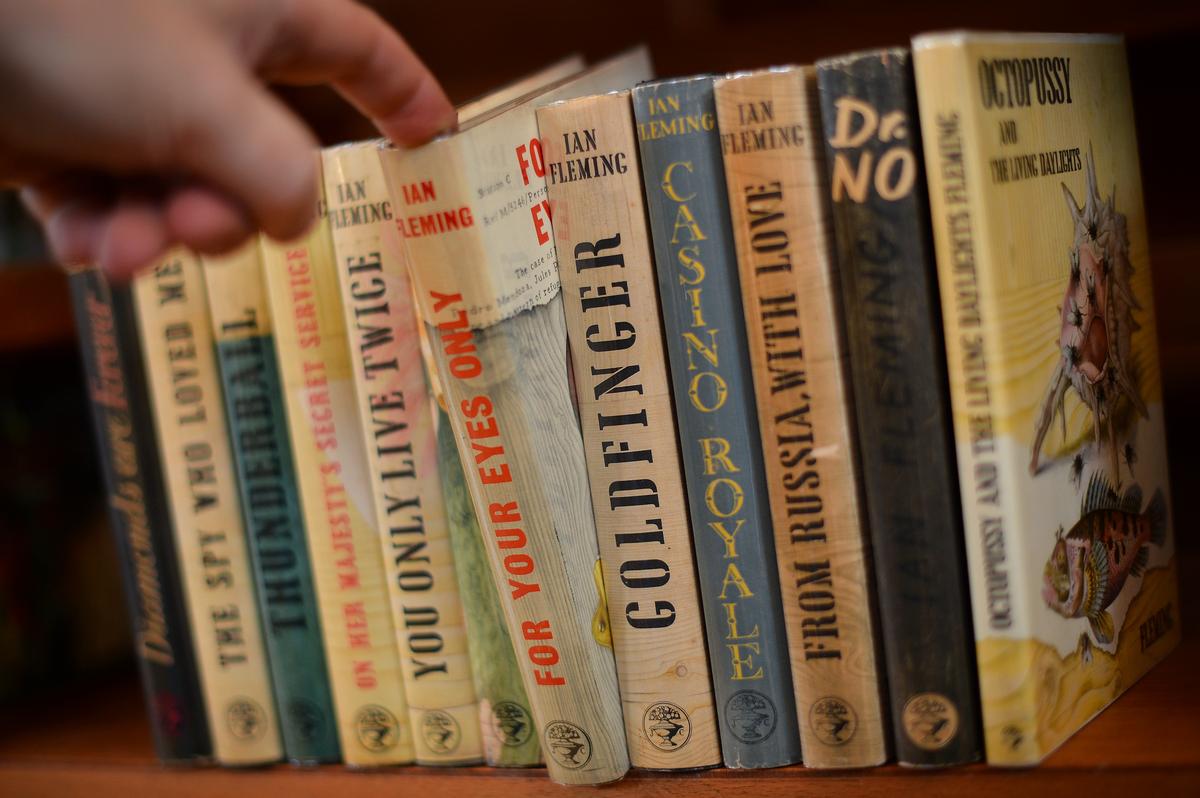

A complete collection of first edition copies of Ian Fleming’s James Bond books at the Chelsea Antiquarian Book Fair in London.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

His novels, say ‘Casino Royale’, ‘Goldfinger’, ‘From Russia With Love’ et al, then are more than a series of sensational fantasies based on outlandish plots?

Yes. He wrote what he knew. They were grounded in reality and a truth that Fleming could not reveal but had intensely experienced. By converting his lived experience into fiction, and updating it, he released the burden of that knowledge. He had to get it out.

Did you enjoy writing this biography? What are you working on?

Once I jumped headlong into the project, I enjoyed finding out about Fleming, but it was difficult to pin him down as he contained multitudes. Only at the very end did I glance across at his photograph, which had been on my desk for four years, and that he had given to his Swiss fiancee Monique; all this time, he had been impenetrable, but suddenly I looked through the veil of cigarette smoke and felt I understood him, and better than that, quite liked him. I am primarily a novelist, as you know, and am working on a new one.

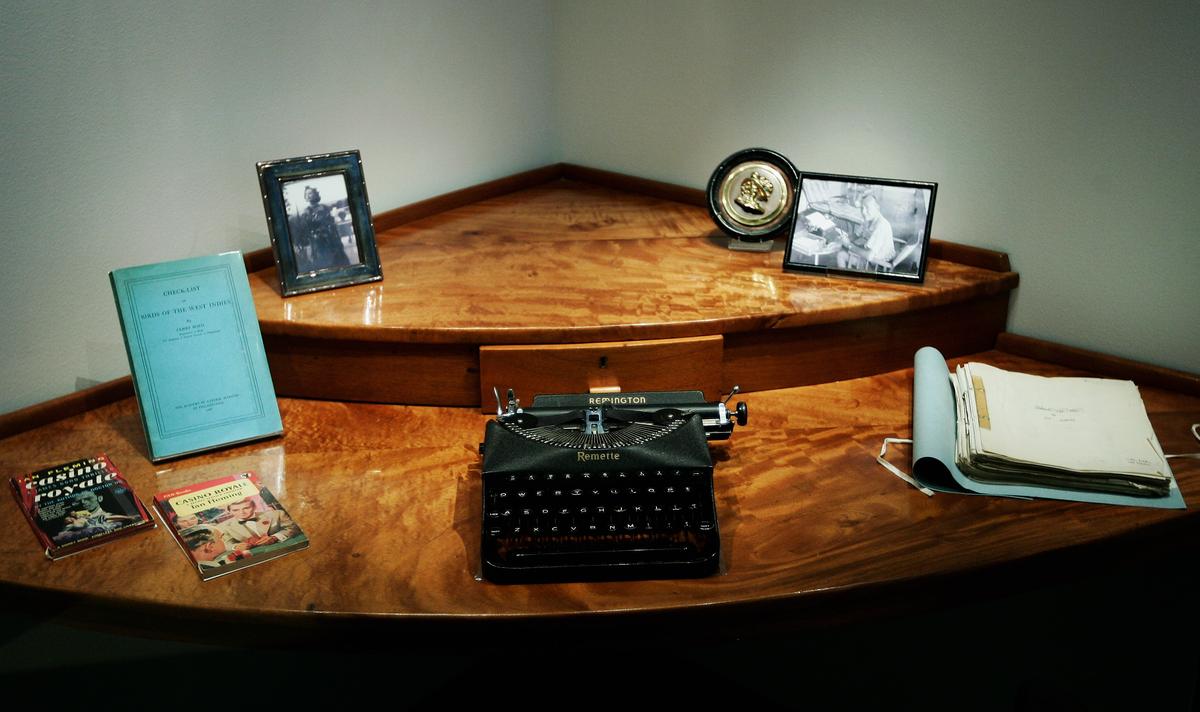

Ian Fleming’s original desk from where he wrote many of the James Bond 007 books, on display at an exhibition at the Imperial War Museum, London.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Ian Fleming: The Complete Man; Nicholas Shakespeare, Harvill Secker/PRH, ₹1,399.

sudipta.datta@thehindu.co.in