Although Ieoh Ming Pei, aka I.M. Pei, lived for over a century, building an iconic global practice, a major retrospective of his work was long delayed. Curated by Aric Chen and Shirley Surya, the exhibition which opened in 2024 at Hong Kong’s M+ Museum has been more than seven years in the making. Pei had dismissed the idea of a retrospective for years until this one, before he died in 2019.

In October, the exhibition travelled to Doha where it is spread over two venues till February. I.M. Pei: Life in Architecture displays his professional journey at the Al Riwaq gallery, while I.M. Pei and the Making of the Museum of Islamic Art: From Square to Octagon and Octagon to Circle is a more personal tribute at the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA), which Pei designed at the close of his long career. It features 400 objects, including never-before-seen drawings, models, photographs, films and archival material.

I.M. Pei: Life in Architecture displays his professional journey at the Al Riwaq gallery, Doha.

| Photo Credit:

Image courtesy Qatar Museums

IM Pei: Life in Architecture show at the Al Riwaq gallery, Doha.

| Photo Credit:

Image courtesy of Qatar Museums

The model for Louvre Pyramid at IM Pei: Life in Architecture show.

| Photo Credit:

Image courtesy of Qatar Museums

Arranged in six sections, the exhibition is a demanding and concentrated viewing of drawings, maquettes, videos and sculptural reproductions of some of his masterly designs. In films and videos, Pei acknowledged the influence of Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier, although he softened the harsh effect of Brutalist architecture. Presented like a vast, austere drawing board, the exhibition reveals the depth of his practice, from public housing to grand projects, such as the Louvre Pyramid and the MIA.

A work at the IM Pei: Life in Architecture show at the Al Riwaq gallery.

| Photo Credit:

Image courtesy of Qatar Museums

The IM Pei: Life in Architecture show.

| Photo Credit:

Image courtesy of Qatar Museums

Blending various styles

So far-flung and culturally diverse were the geographies that he worked in, that Pei’s practice may best be understood through maquettes and photographs of his rich, and frequently controversial career. Hailing from an artistic family that traced its roots to the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), Pei was fascinated by Shanghai’s classical Chinese garden and Shikumen architecture, which blended Chinese and western features. At 17, he went to University of Pennsylvania, and his bamboo work on display at Harvard reveals how he was thinking of enhancing modernist architecture in China.

China closed its borders between 1949 and the 1970s, and Pei formed his own company to enter the building boom in America, then dominated by architectural giants, including Frank Gehry, Norman Foster and Louis Kahn. Pei received several museum commissions early on. The models on display include the Emerson Museum (1961-68) with galleries in four cubes around a central atrium, the Johnson Museum at Cornell, Des Moines Art Centre and the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington with its challenging triangular design — all airy, accommodative civic spaces.

An unkind world

In spite of his great success, the global fraternity of architects was not always kind to Pei and that may have contributed to the lack of research on his practice. His dramatic effects with sharp angles, a touch of sci-fi worldbuilding and designs, which were considered overly cool or detached, were panned when they first appeared. Several of his most innovative projects remained ‘paper architecture’: from a museum in Athens based on a Greek Orthodox church to the unbuilt Polaroid tower. That Pei was undeterred is visible in his design for the U.S.’s Dallas Civic Center, with its sharp angular wedges, inverted pyramid form and sci-fi Brutalist design, that featured in the film RoboCop (1987).

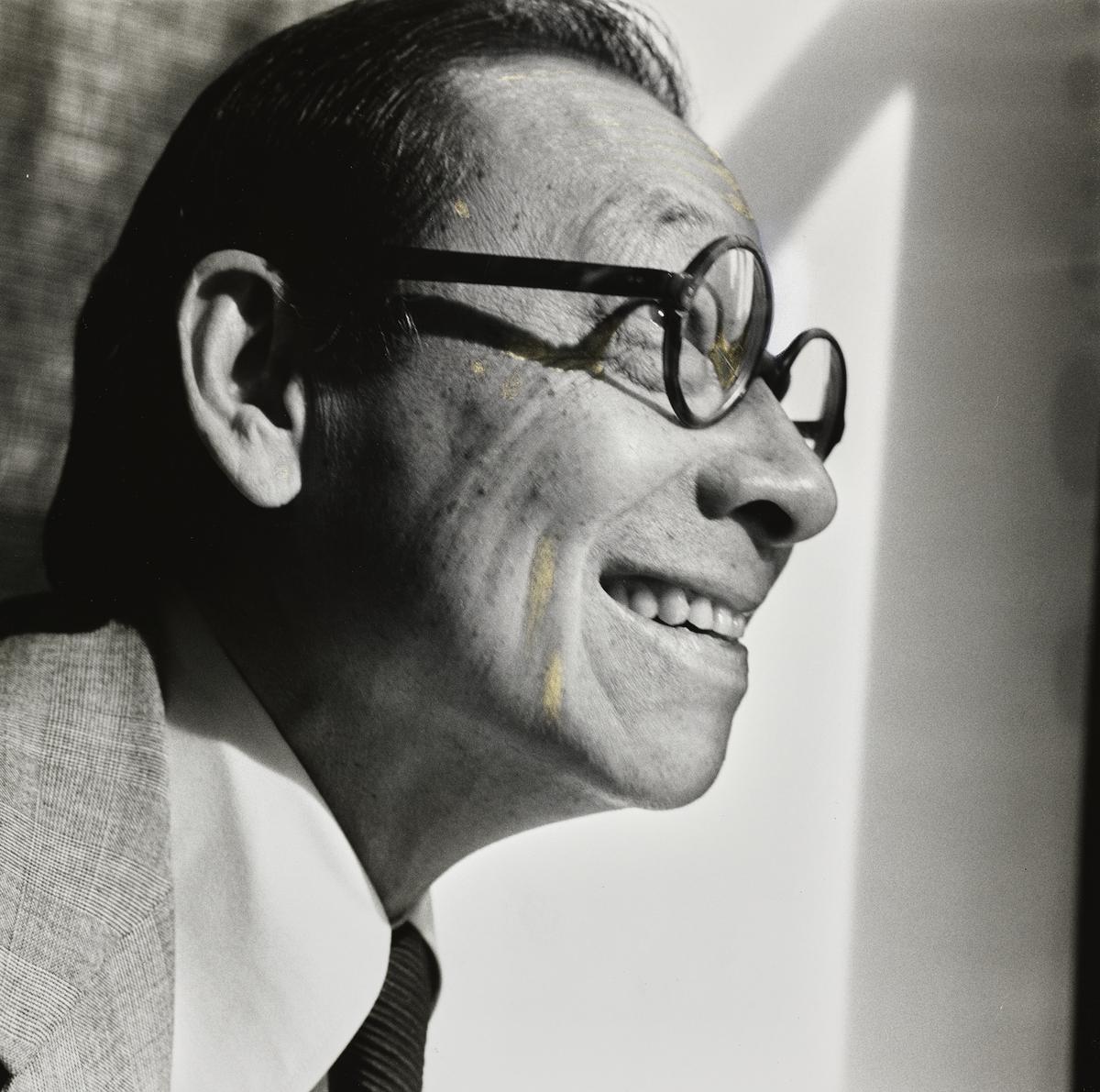

Portrait of I. M. Pei from 1976.

| Photo Credit:

Irving Penn, Vogue © Condé Nast

The Guangzhou-born, Pritzker prize-winning architect worked closely with artists and integrated the works of Henry Moore and Alexander Calder into his design. Particularly interesting is the shift that Pei was to make from designing in museums and public installations in the U.S. to working in China, notably his razor-sharp, edgy design for the Bank of China. In a 1970 photograph, Chinese officials in Mao suits curiously examine his model for Fragrant Hill hotel, built on a former imperial hunting ground. Pei determined not to create a tower in the ancient Forbidden City, choosing instead a modernist building. He called it his most difficult project. The unorthodox mix of styles in the building is recognised as influencing generations of Chinese architects, and also led to Pei’s spectacularly successful Suzhou Museum (2006).

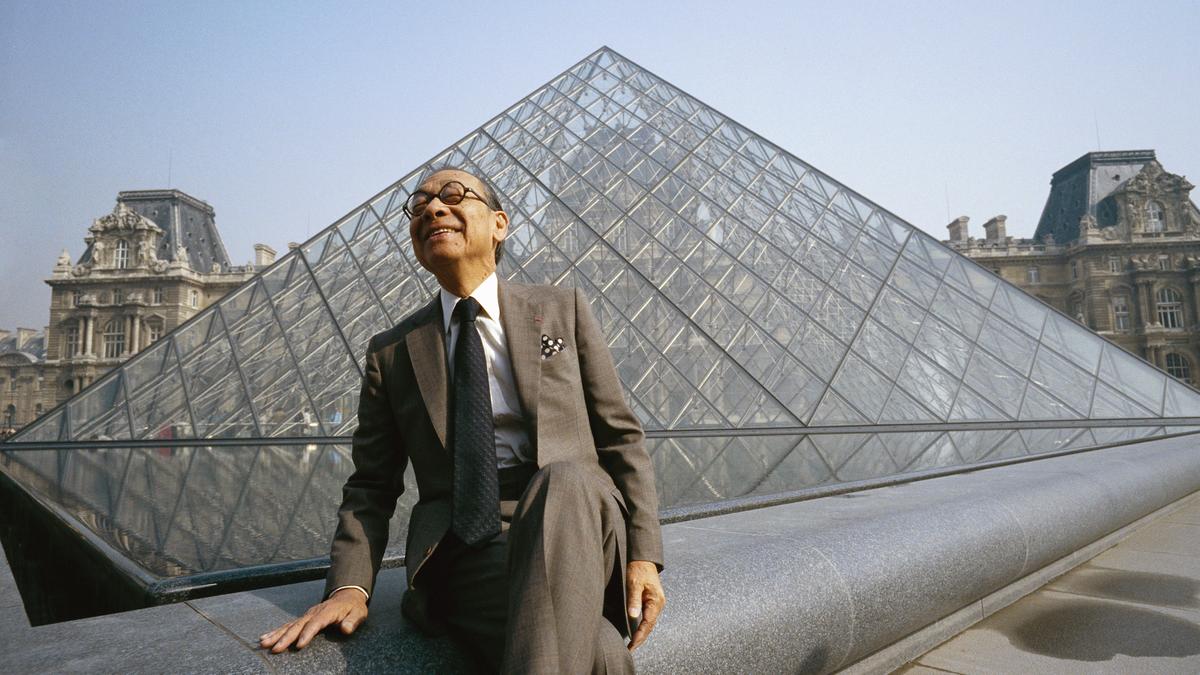

Proximity to power

Famously patronised by Jackie Kennedy Onassis who gave him an out-of-turn commission to design the Kennedy Memorial Library, Pei was immensely prolific and attracted the envy of his contemporaries. Francois Mitterrand chose him for the renovation of the entrance to the Louvre. When he first presented the design that resembled the Pyramids, Le Monde newspaper’s mockingly spoke of his design as a “house for the dead”. Undaunted, Pei made a mock-up of it in strings, and was photographed with a fist pump in the French papers.

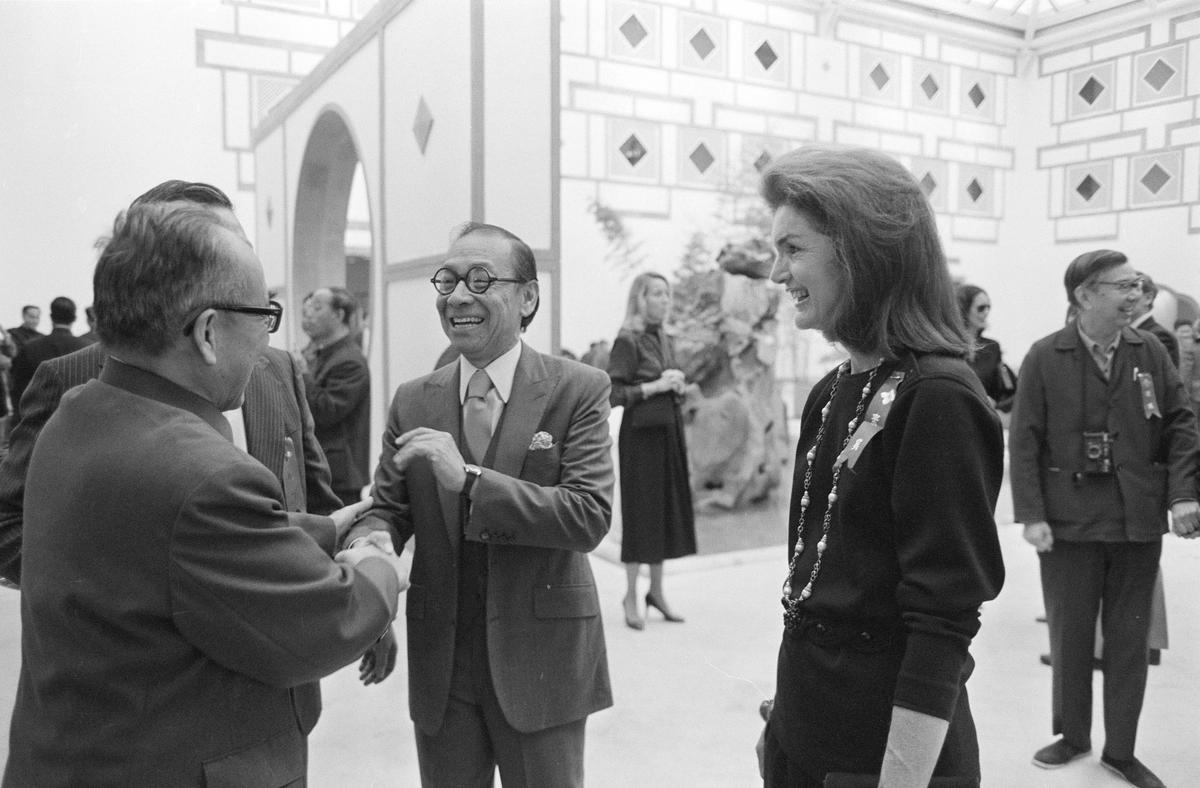

I.M. Pei (centre) with the former U.S. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and guests at Fragrant Hill Hotel’s opening in 1982.

| Photo Credit:

© Liu Heung Shing

His proximity to power is evident in his selection for the MIA by the Emir of Qatar. Yet again, Pei was not the winning architect. Fresh from his controversial and highly lauded design of the Louvre Pyramid (1989), Pei was chosen for the Doha project ahead of front-runners such as India’s architect and urban planner, Charles Correa.

Musings on the mosque

Coming out of retirement to accept the MIA’s commission (completed in 2008), Pei insisted on a waterbody surrounding the structure. Acknowledging his ignorance of Islamic design, he travelled extensively to such cultural sites as the Great Mosque in Damascus, Spain, Tunisia and Fatehpur Sikri to understand the essence of Islamic architecture. It was at the ninth-century mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo, which draws on a square, octagon and a circle for its central dome, that he had an epiphany for his virtuoso building. As we approach the gleaming white building, on graded steps with flowing water, Kashmir’s Mughal Gardens and Spain’s Alhambra palace come to mind.

Doha’s Museum of Islamic Architecture, the first mega-museum in the Gulf, is an imprint of local Arab identity in neo-vernacular style.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Biographical material on Pei on display at The Museum of Islamic Art.

| Photo Credit:

Chrysovalantis Lamprianidis

To view the biographical material on Pei on an upper floor of the MIA and then the marvels of the Islamic world on the lower vault-like level is a breathtaking experience. The entire space is dedicated to art treasures, including rare Persian paintings, the 19th century Damascus Room, and Safavid, Iranian and Ottoman pieces in glass, ceramic and textiles. Indian viewers will be especially taken by the display of wedding jewels, from the erstwhile royals of Bharatpur, Patiala and Jaipur, that dazzle and dismay. While the government of India stepped in to prevent the export of the Hyderabad crown jewels, these extraordinary pieces of brilliant craftsmanship now have another resting place.

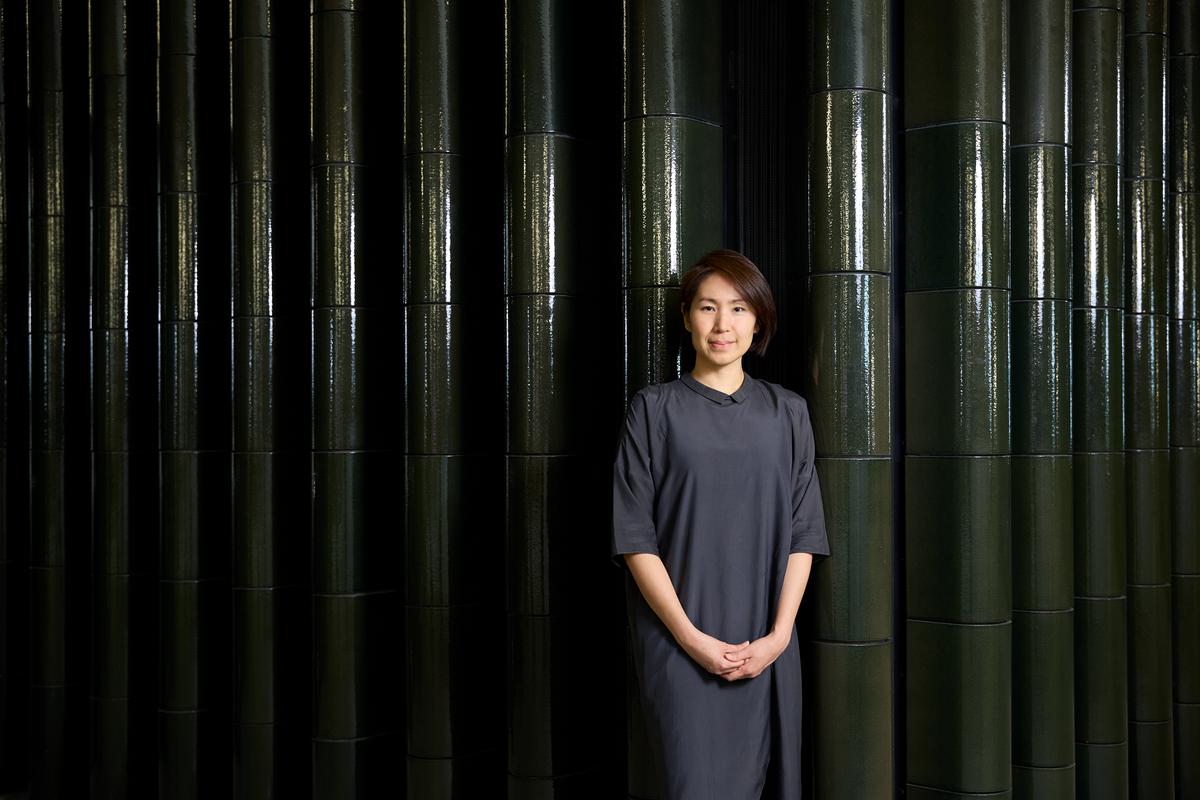

Portrait of Shirley Surya, curator, ‘Design and Architecture’, M+, Hong Kong, and co-curator of ‘I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture’, Qatar.

| Photo Credit:

Winnie Yeung @ Visual Voices/Image Courtesy of M+, Hong Kong

Portrait of Aric Chen, director, Zaha Hadid Foundation, London, and co-curator of ‘I. M. Pei: Life Is Architecture’.

| Photo Credit:

Mark Cocksedge

The exhibitions are on view till February 14, 2026, at Al Riwaq gallery and at the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha.

The art critic and curator is based in New Delhi.

Published – December 12, 2025 02:17 am IST