In August 1971, a psychology professor at Stanford University conducted a study in which college students were offered money in exchange for participating in a two-week prison simulation experiment. Philip Zimbardo wished to understand what such an environment would do to their psyche. Through coin-flips, the participants were segregated into ‘prisoners’ and ‘guards’. In just 24 hours into the experiment, the crucible gave in, with prisoners rebelling against the guards, and the latter resorting to psychological abuse to show prisoners their place. The experiment reached unspeakable heights and was terminated on the sixth day, with the intervention of psychologist Christina Maslach.

In 2015, Kyle Patrick Alvarez made a cinematic retelling of the experiment, called The Stanford Prison Experiment, which incisively took viewers through the experiment; while every progressing situation reveals intriguing psychological results of life in prison, the epilogue is startling, where the participants spell out their experience. Several concurred that putting on a uniform of authority automatically brings out their worst, apathetic selves. From the beginning, we see Michael Angarano’s prison guard character, the despicable John Wayne, ‘enact’ how he believes guards should be. When confronted, he expresses his disbelief in how his abusive authoritarian ship wasn’t questioned enough.

Much of this echoes Tamil filmmaker Vetri Maaran’s belief that the pyramid of power is such that it cannot function with empathy. As the high recidivism rates point toward, most prisons seem far removed from their rehabilitative purpose, now existing as a mere symbol of apathy, a reminder of human despicability.

Prison, a microcosm of society

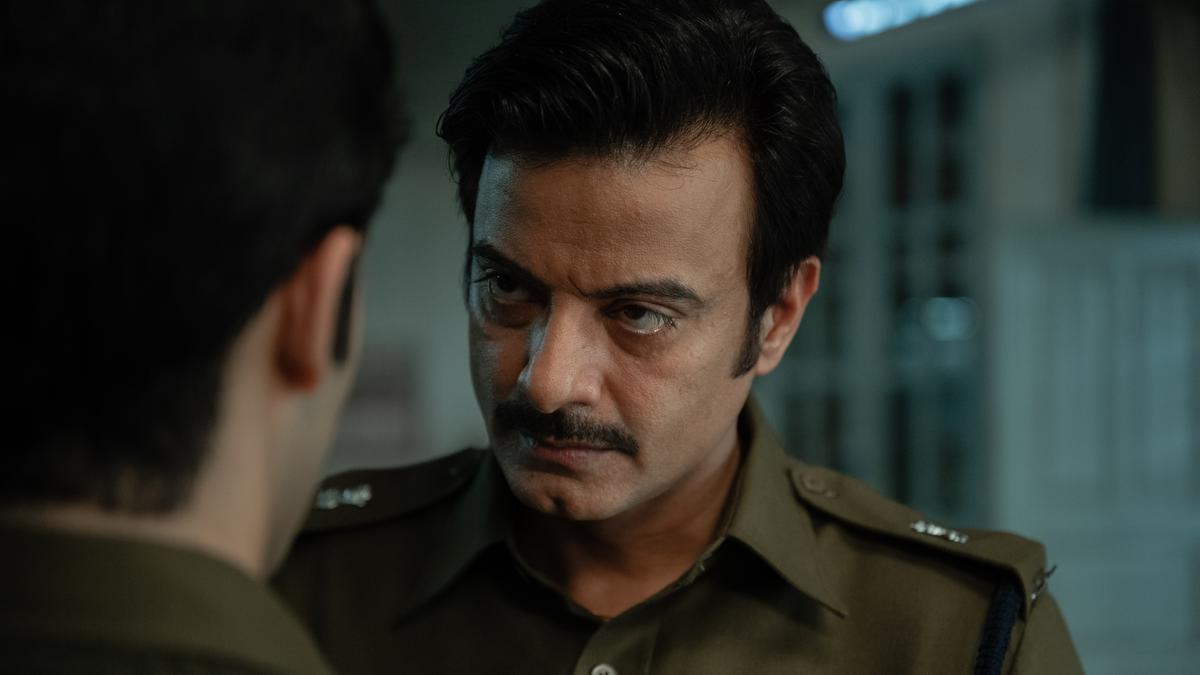

As several films and shows have shed light on, the prospect of jailing someone is currency by itself, used for political and personal reasons. Filmmakers have captivatingly explored the prison system, attempting to unearth hushed, perverse secrets of our civilised world. Though a sanitised retelling of real events, Netflix’s Black Warrant explored the psychological nuances of life in prison and the politics that make the governing system anything but rehabilitative. When we first meet the infamous Bikini Killer, Charles Sobhraj (Sidhant Gupta), in the series, the pull his presence has on the guards of Tihar seems heroic; but when you see our honest hero (Zahan Kapoor, as Sunil Kumar Gupta) repeatedly ask favours from Sobhraj, the curtain drops. You also see the system for what it is when Sunil’s attempts towards rehabilitation are hindered by his superiors. Like in a particular episode in which criminals Billa and Ranga are hanged, many scenes question our biases.

Sidhant Gupta as Charles Sobhraj in ‘Black Warrant’

| Photo Credit:

Chandini Gajria/Netflix

Several cinematic titles have taken swings at our moral contradictions. Reduced to their primal selves, humans perversely wish to feel liberated from their own social structures and step out of line, if they could face no consequences. They even self-condition their moral compass to live without guilt. They would know better if they watched Ric Roman Waugh’s 2008 drama Felon, which spectacularly shows how a man — imprisoned for accidentally killing an intruder — is brutalised by a debauched institution and forced to abide by gang rules to survive.

The character of Lieutenant Bill Jackson in Felon embodies a corrupt cog in the prison wheel, a superior who has succumbed to the pressure of prison life. Watching Jackson break down in a parking lot echoes Samuthirakani’s character in Vetri Maaran’s Visaranai, which remains the most gut-wrenching depiction of the filth running deep in our prison system. Post the release of the film, reports cited testimonies of viewers experiencing fear for men in khaki; the many news reports of fake encounters in southern India have only added to the image that Visaranai and successive Tamil films like Jai Bhim and Viduthalai have painted of our police.

Prison, a primitive jungle

In a confine, the only colleagues you have are your prison mates. They could be your friend or enemy, but most importantly, they are the only resemblance of any human relationship you have during your time in jail. They can be your voice of consciousness — like Balaji Sakthivel’s Bashir in Sorgavaasal, a cook who helps RJ Balaji’s Parthiban find purpose — or prove to be ladders to the higher levels of prison hierarchy — like Selvaraghavan’s Siga in the same film. Many Hollywood films have shown how normalised sexual abuse among inmates is in prisons, like 2000’s Animal Factory. In the Steve Buscemi film, when Willem Dafoe’s Earl Copen helps 21-year-old Ron Decker (Edward Furlong), the latter seems hesitant, wondering if all this kindness is a manipulation tactic. Copen, however, proves to be an angel; he educates Ron on the quagmire that is life in prison.

Vetri Maaran, on the sets of ‘Visaranai’

In Felon, when Wade Porter (Stephen Dorff) is lodged with a hardened criminal (Val Kilmer, as John Smith), in a Special Housing Unit, you understand Porter’s paranoia. Surprisingly, in a place where you survive by teaming up with a gang and fighting at a pit, you realise that while Smith isn’t an angel, he isn’t a demon either. A quote from Smith vividly paints how prison “desensitises” all: “The first time you see a guy’s face cut up, you puke. The second time, you are concerned. After a while, you step right over and you could give a s***. It’s no different for them pulling the trigger. Make no mistake, we are all in prison.”

Through films, we could also witness unnervingly how social evils like casteism, bigotry, and racism show their hideous faces within prison halls, like with the segregation between Whites, Blacks and Hispanics in many Hollywood prisons. Black Warrant too touched upon this, by setting its story during a sensitive period in India’s history, showing the plight of the Sikhs in the aftermath of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984; a well-staged scene featuring Sunil and Paramvir Singh Cheema’s Shivraj Singh Mangat, after being suspended for standing up for Sikhs like himself, shows how such hostility could break the best of us, even fissuring precious relationships.

A redemption arc?

On the mainstream Indian cinema front, prisons can be a launching pad for the wronged hero. 2023’s Sapta Saagaradaache Ello told the story of a young couple whose lives turn tumultuous when the man is asked by his boss to take the fall for a murder. Manu (Rakshit Shetty) does it so he can come out soon and lead a good life with Priya (Rukmini Vasanth). Betrayed, his spirit is torn from within as the walls of the prison close in. Usually, it’s the male hero, but in cases like Sriram Raghavan’s Ek Hasina Thi, a heroine (Urmila Matondkar’s striking performance) seeks vengeance after a wrongful conviction.

Prison escape dramas like Escape From Alcatraz and The Shawshank Redemption deliver nail-biting narratives, but what if the hero voluntarily enters the prison for a reason? Nothing comes close to the explosive intermission sequence inside a prison in Vada Chennai. Vetri Maaran’s command shines through in a scene set at a carrom board competition in the prison yard, in which a leading character is revealed as an insider.

No other setting lends such nuanced takes on the human condition as much as the state-approved confine. Given the long history of our prisons and the innumerable individuals whose stories are yet to make their way to our screens, prison dramas remain a potent genre that lets us understand our flawed selves.

Published – February 21, 2025 05:07 pm IST