Japanese filmmaker Hirokazu Kore-eda’s films are as easy to watch as they are difficult to digest. Four abandoned siblings living in a tiny apartment, a family resorting to shoplifting to overcome poverty, brothers who have been separated from their parents, and infants who were exchanged at birth. The stories Kore-eda chooses to tell are deep visual incisions into the contemporary Japanese family units. At the centre of this, he places the child.

This is not particularly a novel trick. In cinema, along its evolution and across countries, children’s characteristics have been made the site of exploring a nation’s emotions. They have been represented as keepers of innocence when the world around them has gone corrupt. Subsequently, children have also stood for a vulnerability, threatened by a changing society, especially during the Second World War. Their ability to hope has doubled up as a community’s hope for a better time, and they have been made a conduit for complex adult feelings.

Kore-eda has worked with children for over two decades now, starting first as a documentary filmmaker with Lessons from a Calf (1991). The documentary ends up foreshadowing the kind of themes Kore-eda would return to in his films. Young children, learn to take care of life and gain wisdom from that experience.

A still from ‘Lessons from a Calf’

Kore-eda is not the first filmmaker to centre children, but he is unique in the way he centres them even in the production stage. Weaving the adult understandings, around the children’s assumptions of the world, his films are harrowing because they present the stark realisation of the gap between the different realities inhabited at different stages of life. His 2023 film Monster dials up the intensity of this emotion and makes it even more obvious.

‘Listening is much more difficult than speaking’

When working on one of his most seminal films, Nobody Knows (2004), Kore-eda used to regularly update the ‘Messages’ section of his website. An entry from March 2003 focuses on his approach to documentary, which he says relies more on listening, rather than the filmmaker’s intervention. “Listening is much more difficult than speaking,” he wrote.

Unsurprisingly, he extends the same principles to his scripts, which are often keen on listening to childhood.

In Nobody Knows, Kore-eda’s follows four siblings who have never met their fathers and are abandoned by their mother.

A still from ‘Nobody Knows’

Akira, the eldest one, is left with some amount of money, and unconvincing promises by his mother that she will come back. He holds out some hope, but soon makes peace with reality, and attempts to find ways for his siblings to survive. Their predicament is made worse by the fact that they cannot openly ask for help, because this will result in them being separated by the social services. They end up living invisible lives, which is what the filmmaker is interested in depicting. Often placing Akira in crowded marketplaces, he forces the audience to realise how none of the adults around him are unaware of his reality.

Akira and his siblings have been raised to uphold themselves, much like other children in Kore-eda’s films whom we usually meet in tough situations. In I Wish (2011), brothers Koichi and Ryunosuke live separately, with one parent each following the parents’ divorce. While not as dire as what Akira and his siblings go through, Koichi and Ryunosuke share with them the ability to hope — a concept that finds its way in nearly all Kore-eda features.

An expanding universe

Minato and Yori, the two leads from Monster are shown discussing the concept of ‘The Big Crunch’, which Yori describes as a phenomenon according to which “the universe will keep expanding, and in the end when it can’t get any bigger, it will split.”

A still from ‘Monster’

Kore-eda’s universes expand too. Sometimes inspired by real life events, and sometimes taking cues from the actors, Kore-eda’s scripts follow an identifiable pattern. They begin with hopelessness, caging the child in a situation created by the adults around him. Yet, being a child, he seeks out a solution with the hope that things will work out. It plays out almost like indulging in a fantasy, a hopeful version of a world that the child believes in. Then, usually, Kore-eda likes to dismiss this notion with a finality. He tends to make the child’s version of the world around him meet the adult version, like an imposed new reality.

The Shibata family, in Shoplifters (2018), seems to be slowly finding its footing on solid ground. Buoyed by a system of shoplifting, and later cashing in on the pensions of dead grandparents, Kore-eda charts an alternate reality for them, which is later shattered by Shota, the young boy. When he watches his younger sister also begin to shoplift, it confirms his suspicions that maybe the ‘ethical’ explanations of shoplifting that he has been given by the adults who encouraged him, will not be of use when his sister gets into trouble. It ends up breaking the family apart.

A still from ‘Shoplifters’

Similarly, the audience follows Koichi and Ryunosuke as they make their way to a bridge to see two bullet trains pass each other, believing that they hold miraculous powers. When the time comes, neither of them can bring themselves to wish for their parents to reunite. Instead, they just resignedly agree to the current situation.

The disconnect between adults and children is heightened and made most obvious in Monster when Kore-eda opts to show the same incident from different perspectives. The adults (like the audience) are barely able to make sense of what is happening until Minato lets us into his frame of reference. The final sequences of the film, according to Kore-eda, reflect a reconciliation of Minato and Yori with their own queer identities, as they shed society’s imposed realities, and accept themselves.

The risk fantasy of a better reality, that even adults indulge in, is shattered by the child who seeks truth, meaning behind his actions.

A detached approach

Several of Kore-eda’s interviews include some variation of the question asking him about his experience of working with children when every other director finds it difficult. As a director, Kore-eda’s consistent response has been that he simply doesn’t direct these children.

Marrying the imaginations of fictional films, with the realism of documentaries, Kore-eda opts for a more detached approach when it comes to working with children. Seeking the most natural possible reactions from them, while in the presence of several cameras and filming equipment, he ensures that they know as little about the film’s technical details as possible. This often plays out with him not giving them the screenplays, or even dialogues. He explains the scene to them on the day and briefs them on the dialogue.

What resulted is the youngest-ever winner at the Cannes film festival in 2004 for best actor, Yuya Yagira for his portrayal of Akira in Nobody Knows.

While detached and impersonal, Kore-eda’s approach ultimately results in tender performances. Though he may not want the actors to be influenced by what he has written for the film, he borrows a lot from them to make the onscreen character more lived-in.

Koichi and Ryunosuke in I Wish are portrayed by real-life brothers whose interactions led Kore-eda to revise the script for the film.

A still from ‘’I Wish’

Nobody Knows which shows the siblings grow over a year, was filmed in the same time frame. When the children returned to the set after weeks-long breaks, he asked them to write and draw what they remembered about the apartment, which he later used as inspiration to tweak his script.

In the case of Monster, he took a more conventional approach when directing the child actors but asked them to “show what they are hiding, what they don’t want other people to see.”

An act of replication

In her book The Films of Kore-eda Hirokazu: An Elemental Cinema, Linda C. Ehrlich calls Kore-eda’s technique “listening to childhood,” which she likens to listening to what is unsaid.

It is not possible to “capture” childhood on film, not in the most honest sense of the way unless you’re shooting a documentary or a home movie. When filming fiction, a pre-written script is acted upon, in certain directions. It then therefore becomes an act of replicating, or acting out childhood.

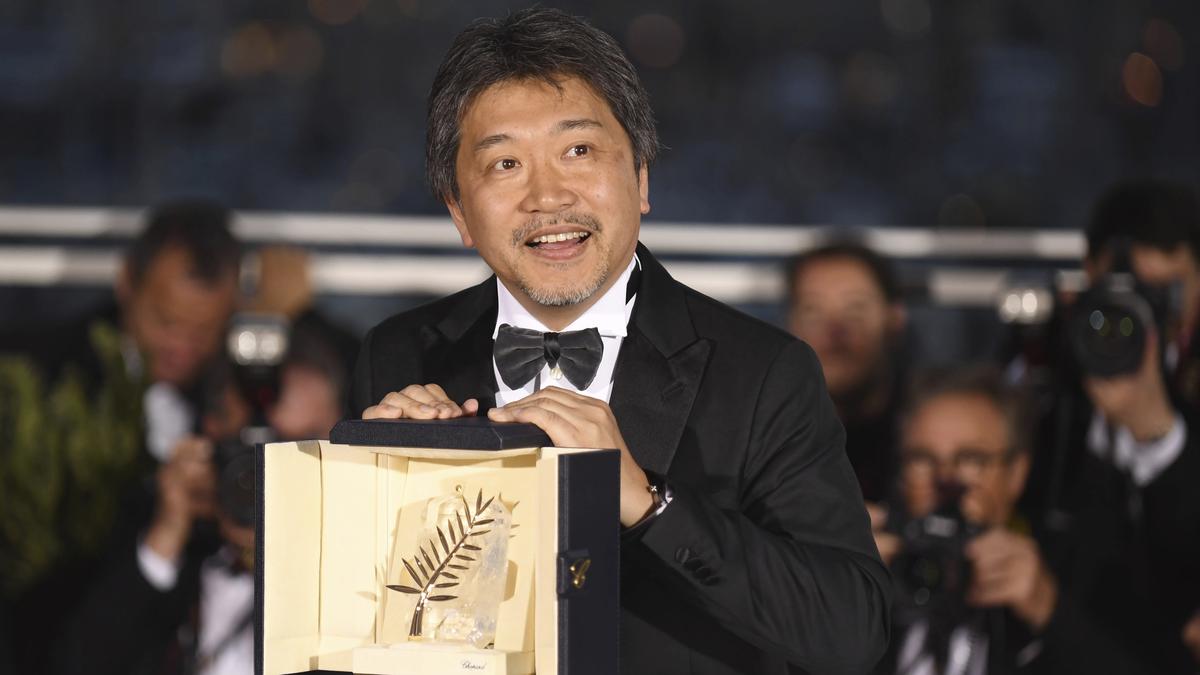

Director Hirokazu Kore-eda

| Photo Credit:

STEPHANE MAHE

How Hirokazu Kore-eda builds his stories around characters that are inspired by the actors themselves, how he frames the shots to accommodate the habits of the actors, and how he encourages the inputs of children, allowing to them somewhat authentically bring their childhood to the set.

Meanwhile, where Kore-eda’s writing is concerned, it remains unflinching in hammering home an unpleasant truth: we can only observe, appreciate, and maybe recall the experience of childhood, but can never fully understand it again in all its complexity… because it is impossible to fully suspend our belief in our current reality.