Jodhpur is a city of marvels, of which the Toorji Ka Jhalra is among the most iconic. Around this stepwell, where the water plunges hundreds of metres deep, the Walled City comes to life — old heritage buildings rubbing shoulders with new cafes and boutiques, narrow lanes packed with locals and cars leading to sprawling havelis. Looming over it, the Mehrangarh Fort stands atop a hill, its halls abounding in art, textiles, and historical artefacts.

These treasures and Jodhpur’s history led Shon Randhawa, founder of Sutrakala Foundation, and curator Mayank Mansingh Kaul to the city, which is now host to Surface, an exhibition positing Indian embroideries and surface embellishment as art. The exhibition stems from years of dialogue and research between Randhawa and Kaul. “I was fascinated that surface embellishment could be a medium of art,” says Randhawa, whose love for needlework is evident in her clothing labels, Patine and Talitha. She founded Sutrakala in 2023 to enable research and innovation in Indian textiles, and ‘Surface’ marks the non-profit’s first such exhibition.

Shon Randhawa and Mayank Mansingh Kaul

The idea, adds Kaur, who curated the show, was to go beyond the commercial aspect of embroidery. “India is at a high point in terms of its experimentation and innovation with it. On the one hand, we’re creating and exporting the most extraordinary embroideries for the world, and on the other, it [the craft] defines a very important aspect of our bridal and occasion wear, and home furnishings market. Surface allows makers [and us] to reflect on expressions outside of these.”

A culmination of visits to historical embroidery centres, and collaborations with over 30 artists, designers, artisans, and organisations, Surface features close to 60 artworks and installations. Undertaken in association with JDH, an urban regeneration initiative in the Walled City, it is spread across three heritage buildings — Achal Niwas, Anoop Singh Ki Haveli, and Lakshmi Niwas — located around the stepwell. The curation is non-linear, taking into account the flow of tourists in the neighbourhood who may visit the sites independently, but also because, as Kaul says, each venue has a visual language that’s quite distinct.

Sumakshi Singh’s Surface as Structure: Monument as Mirage

Beyond definitions

Beginning at Achal Niwas, artists and creators explore what embroidery can be, if not surface embellishment. Parul B. Thacker’s The Book of The Time Travellers of the World incorporates tiny embroidered dots, fine as paper drawings, to create an impression of sound waves and energetic maps. “We’ve worked with a German company to use a specific thread count and invented our own stitching to create microscopic dots,” she says. The installation draws from an artist residency that Thacker spent sailing around the archipelago of Svalbard.

Parul B. Thacker’s The Book of The Time Travellers of the World

A number of exhibits explore techniques conventionally associated with clothing and home linens, playing with shape, proportion, and texture. In Soar, a series of silk panels designed by Ashdeen Lilaowala, cranes intricately crafted in Parsi gara embroidery take flight. “With so many artists using textiles as a medium, it has become a bona fide art form,” says Lilaowala. “Craft can find ways to move forward, when it is broken down.”

Ashdeen Lilaowala’s Soar

For many, this means reimagination. Take textile designer Swati Kalsi, who dominates the exhibition with nine installations drawn from two projects with sujini embroidery and Chamba rumal (embroidered handkerchiefs). Departing from sujini’s narrative embroidery, her installations Etch and Night Breeze translate the bharua stitch in abstract patterns, reminiscent of fireworks, on kimono-like silhouettes.

From Swati Kalsi’s Chamba Rumal project

The Chamba Rumal project, which Kalsi undertook as a collaboration with Delhi Crafts Council, reinvents scenes traditional to the art form such as vivah (wedding), godhuli (twilight hour), Devi (goddess), and shikar (hunting) in reversible embroidered works of art. A black and white creation titled Shatranj, interpreting contemporary politics on a chessboard, is particularly striking. “I think of them as co-creation, rather than just working with artisans,” says Kalsi, whose artworks and design interventions are the result of long engagement with craftspeople.

Highlighting women’s collectives

Many creations encompass stories of Indian communities practising embroidery and the work of women’s collectives, showcasing indigenous forms such as kantha, sujani, and rabari. Panels by Kutch-based crafts organisation Shrujan showcase the traditional needlework of the region’s Jat and Mutwa communities.

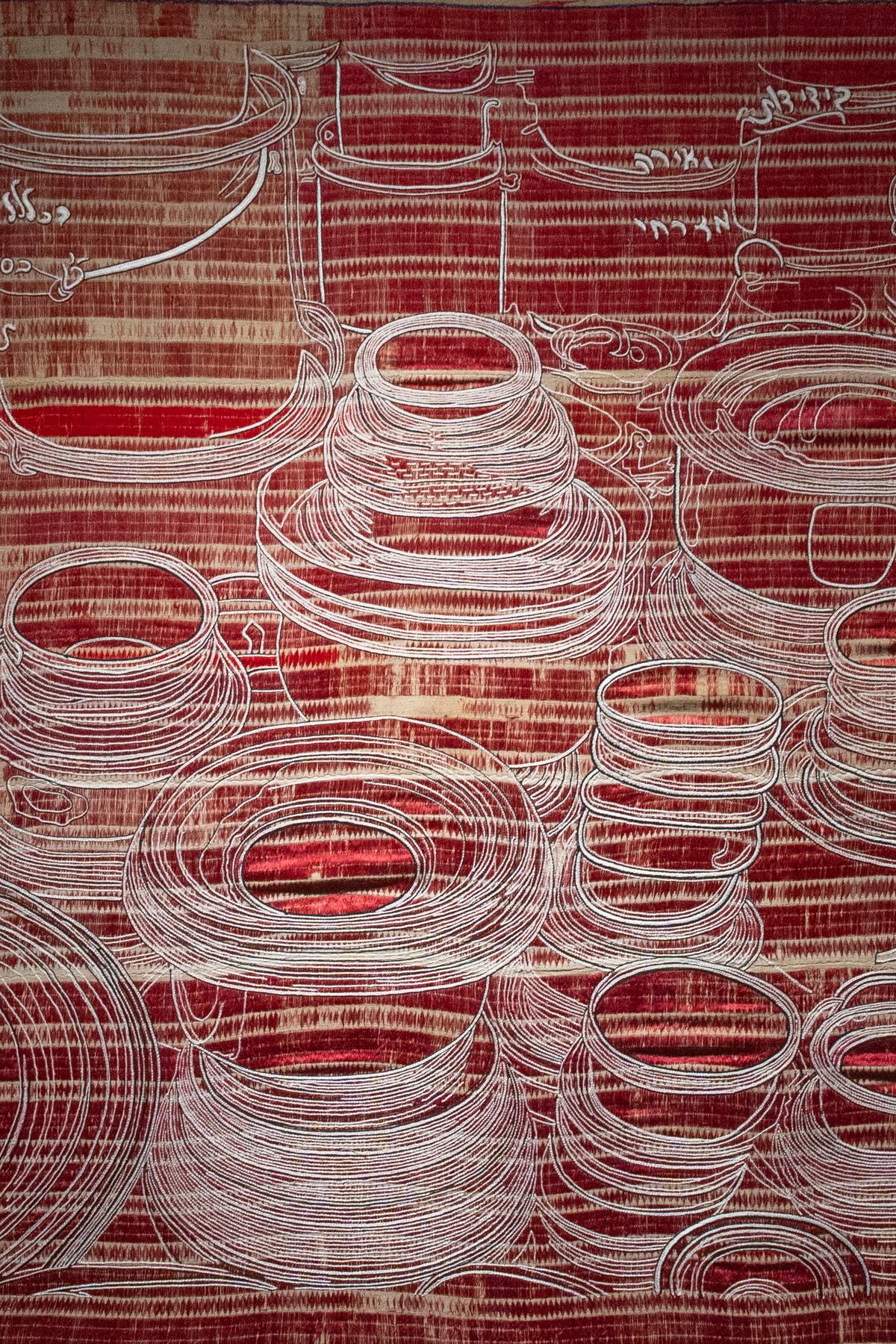

New York-based architect, artist, and designer Ghiora Aharoni’s installations (on exhibit at Achal Niwas), Bagh Phulkari and The Infinite Thing We May Become, use vintage panels of bagh phulkari. He juxtaposes this traditional craft from Punjab with his own embroidery, featuring drawings and text from love letters his mother had written as a young woman.

Detailing in Ghiora Aharoni’s installation

Another stunning exhibit is Aravalli: the Eternal Guardians of Jodhpur, an installation by Karishma Swali and the Chanakya School of Craft, known for training and upskilling women artisans. It features two textile panels, created using basket and chevron weave techniques as well as a bamboo and cotton sculpture that is a “metaphor for the resilience and creativity of women weavers”.

Aravalli: the Eternal Guardians of Jodhpur

Pushing the needle

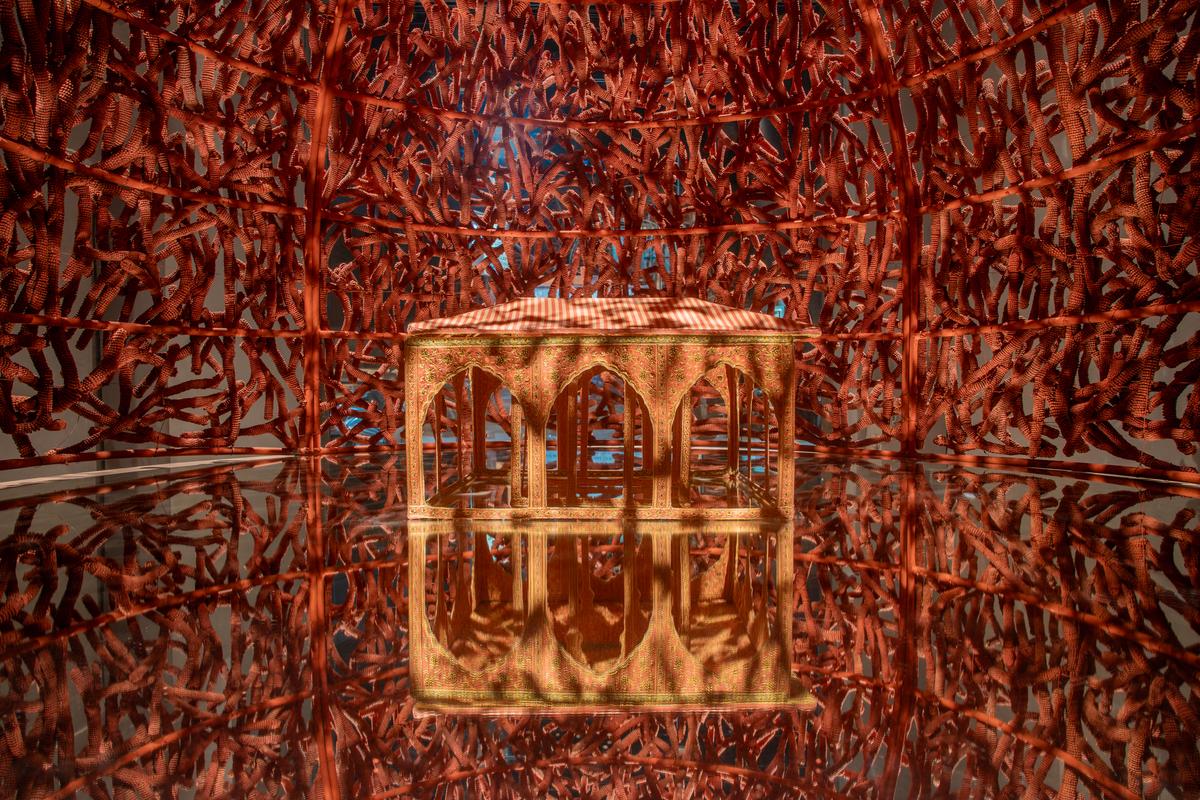

At Laxmi Niwas, the installations evoke abstraction and the avant-garde. In the installation Travelling Roots, Jean-François Lesage, the founder of embroidery atelier Vastrakala, makes the historical Lal Dera — the 17th century Mughal tent belonging to Shah Jahan, crafted from red silk velvet and embroidered with gold threads — his muse. “This piece is made of hundreds of thousands of wooden beads and hand-painted, suggesting the colour of the earth of Rajasthan.” Within the beaded structure stands a miniature Lal Dera, its mirror base reflecting the intricate craftsmanship of the interiors.

Jean-François Lesage’s Travelling Roots

The miniature Lal Dera

Across the three venues of Surface, however, no exhibit stands out quite like Kerala-born Haryana-based artist Shine Shivan’s mixed media installation, Kshetra Dhara. A week before the show opened, two trucks had transported cylindrical packages wrapped in tarpaulin — stuffed with masks, decaying seeds, dentures, scrap fabric, clay pots, toys, discarded decor objects and chicken heads — weighing over 1,000 kg, to the gates of the old city. Shivan then assembled the macabre installation, built as a cave of curiosities, inspired by taxidermy, on site.

Shine Shivan’s Kshetra Dhara

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy @shineshivan

“Our purpose was not to create shock value or attract people. It was just to make art,” he states plainly. But it also challenges the very concept of surface decoration. Can the grotesque be decorative? Shivan’s installation gathers dust and keeps asking this question.

Surface ends on February 23.

The writer and editor is based in Delhi.

Published – February 21, 2025 11:46 am IST