Chay Reds, Ferrous Black: The Untold Stories of Indian Trade Textiles in Sri Lanka

There’s a culture of fraternity at textile exhibitions across India. A culture of support and championing of a common passion, and sharing knowledge. Perhaps I am sensitive to this as someone with a voracious appetite for learning through historical textiles. Nevertheless, I head to Chay Reds, Ferrous Black: The Untold Stories of Indian Trade Textiles in Sri Lanka at MAP (Museum of Art & Photography) in Bengaluru. The exhibition is curated by textile designer and researcher Yash Sanhotra, who fleetingly spent time at The Registry of Sarees. So, here’s a disclaimer: I had every reason to love the exhibition even before I stepped foot into it.

With its palampores (hand-painted, mordant-dyed bed covers and panels) and textile fragments dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries, it is divided into four sections. The first sets the context by tracing trade in Sri Lanka. A model of the Avondster (Swarup Bhattacharya, wood, 2024), a Dutch East India Company cargo ship used for transporting areca nuts — which wrecked in 1659 near Galle Harbour — brings focus to the timeline and maritime trade in particular. And Renuka Reddy’s acclaimed technical dissections of the chintz process inform the materiality of the show.

The model of the Avondster at Chay Reds, Ferrous Black

Tumpals and mythical motifs

A children’s version runs parallel to the main narrative. It is tempting to play the game of finding motifs and clues, and collecting stickers through the exhibition, but a reproduction of Portuguese artist André Reinoso’s Printed Clothing in Seventeenth Century Ceylon (1619) catches the eye. In the painting, the chief of the Paravars, a maritime community, is surrounded by common folk wearing printed/painted textiles — perhaps produced in India — indicating aesthetic and cultural ties between our two countries.

The somana tuppotiya, a traditional wrap-around garment, forms the main feature of the Costume section. The pleated rectangular cloth, which is draped around the waist much like a vesti from Tamil Nadu, albeit secured with a woven sash or belt, captures overlapping influences. Here, Sanhotra also introduces motifs alluding to Sri Lanka’s eclectic preferences in chintz, by the presence of tumpals (a series of triangular shapes that appear in Southeast Asian textiles and art — they often contain other painted patterns within them) on the width of the textile.

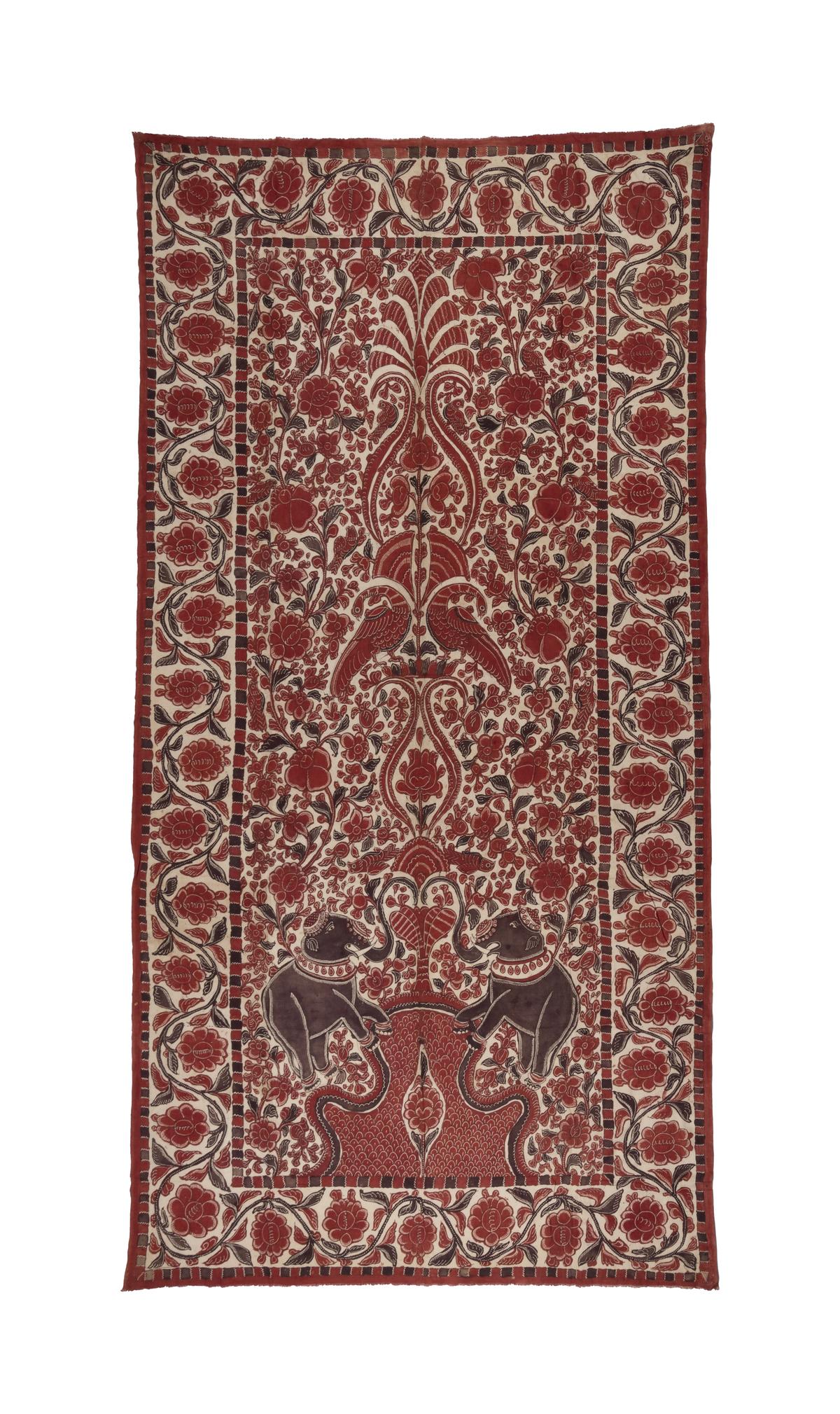

Palampores form the heart of the exhibition. Chay (red) and ferrous (black) are used distinctively to showcase mythical motifs such as the makara (vehicle of goddess Ganga), Gandaberunda (two-headed bird) and Garuda, as well as everyday images of cashews and pomegranates, horses, elephants and peacocks. In all, there are nine large textiles and seven fragments — all relevant to the storyline of maritime trade.

Palampore (19th century, cotton, natural dyes)

The section on Sri Lankan Workshop highlights the Dutch’s focus on producing fine chintz in Jaffna, and how the industry was influenced by textile models from Pulicat in India. The mention of South Indian weavers and dyers migrating to Kandy due to drought, and their involvement in textile production, adds an important layer to the narrative. It suggests a blend of local and migrant craftsmanship that likely contributed to the uniqueness of the chintzes produced during this period.

The exhibition finishes with Sacred Textiles, inferring that the rich red hues are generated due to calcium rich water present within the geography of the land. Motifs and their meanings are used to explain Budhhism, Hinduism, indigenous Vedda traditions (with an emphasis on respecting the natural world). Can an amalgamation of different practices and histories really be explained away by colour?

Lacking textile investigation

The magnificent textiles and objects contribute to an eloquent design language, meant to provoke “further scholarship”. However, very little actual quantitative textile investigation — in terms of the base material, chemistry of the dyes, techniques in application, migration of peoples, mention of textile trading revenues, regional expertise, and competition with other regions of production — receives mention in the curation.

Temple flag (19th century, cotton, natural dyes)

Sri Lanka and India have a history of glorious peace but also devastating conflicts. We share a strange culture birthed on custodianship of faith and language, music, art and architecture. I have always believed that textiles that survive centuries carry within them the poignant currency of this loss and change. If exhibitions are meant to be spectacles, then this is a success. But perhaps it is time for audiences to also nudge the cultural fraternity clique beyond formulaic exhibitions around motifs and colour, in the guise of reflecting deeper meaning on our identities.

The writer studies community, identity and material science as a student of textiles with The Registry of Sarees.

Published – February 21, 2025 10:21 am IST