It is highly possible the last time one heard the word “mica” was in school and in connection to a no-longer-remembered chapter on the earth’s minerals. The Forgotten Souvenir, an exhibition that is currently underway at the Museum of Art and Photography, will not only stir up memories of geography lessons, but also an important one in history, too.

According to Khushi Bansal who curated Forgotten Souvenirs, mica paintings rarely get an exclusive viewing and are usually a part of larger exhibitions displaying Company School Paintings (works of art created during the British era). However, mica paintings came into their own during a specific period of time in India — when royal patronage of traditional art was on the decline and photography was becoming popular.

“This was a period when the British had come to India, the courts were no longer able to support artists and their workshops, and so they started adapting to changing demands and clientele,” says Khushi, adding that the new patrons were military personnel and merchants visiting India; they neither had the time nor the resources to commission large scale works.

“There is a depletion in the level of detail as well as a change in the themes found in art works at the time,” she says, with regard to art works executed during that period. “Usage of the term Company School minimises a lot of other developments in the art scene at that time.”

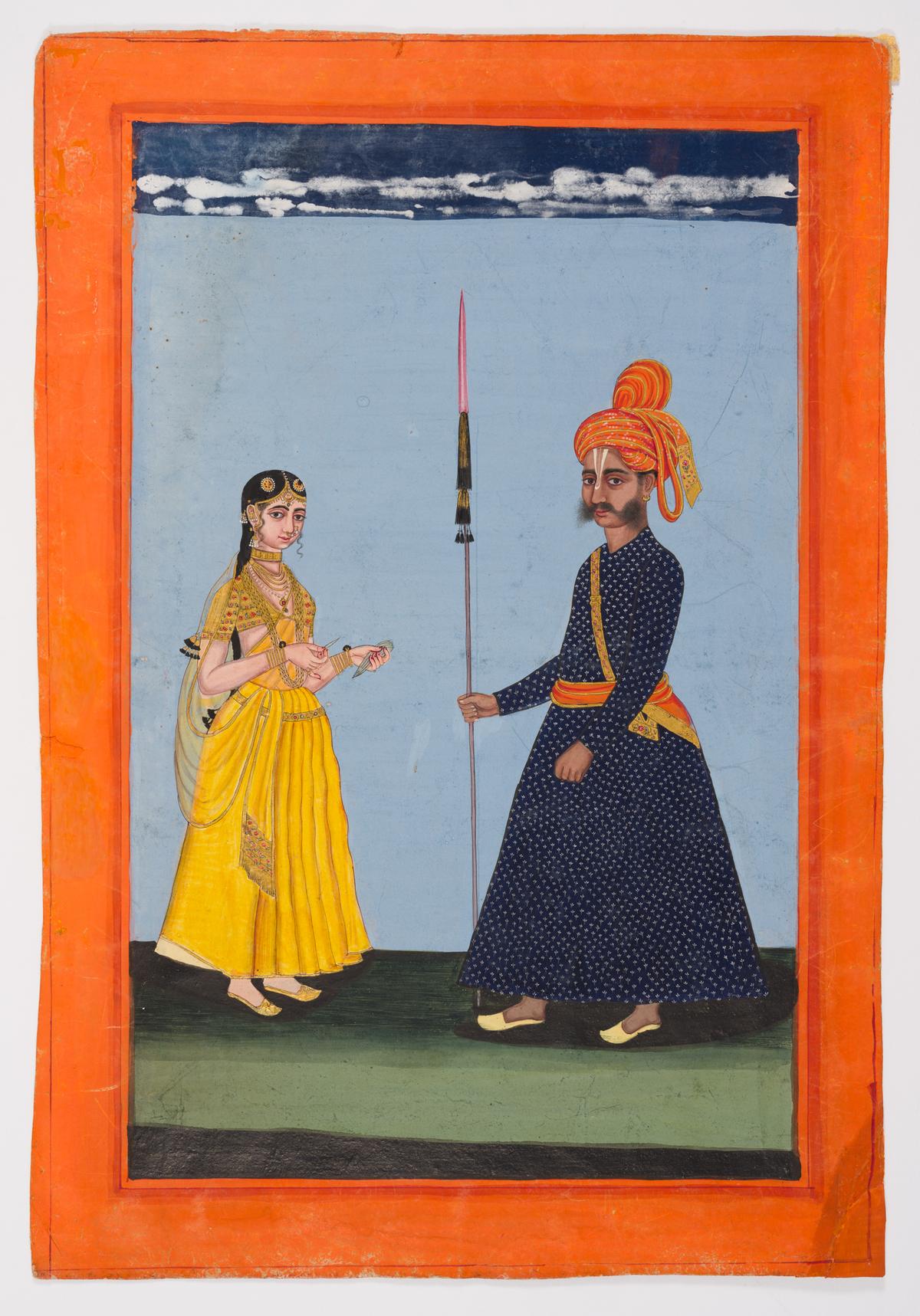

An exhibit from The Forgotten Souvenir

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

However, the biggest transition was that of the medium. Khushi explains, “While art continued to be created on paper, artists also started working on other materials, such as ivory, shell and mica. Mica became an interesting medium because it imitated European glass paintings, and compared to glass, they were relatively easy to transport back to England.”

It is interesting to see how a factor such as the tourist demand for collectibles heralded a change in creative expression. Mica is found in specific parts of the country— Murshidabad, Patna and Tiruchi — and these regions developed specific styles of work with this medium.

The Forgotten Souvenir

This stylistic shift is quite apparent during a walk through The Forgotten Souvenir exhibit. There are the three types of mica paintings — the faceless images, sets of trades and occupations, and deities.

Also on display are samples of mica and it is amazing to see how such a fragile material was used as an art medium more than a century ago. What is even more surprising is how the works have survived the passage of time.

“The artists realised mica couldn’t absorb pigment so they added gouache to stabilise the watercolour, which resulted in vibrant multi-coloured paintings,” says Khushi, who adds that was a digression from the British aesthetics of the time.

The makers of these glass paintings pushed at the boundaries of design and they were used in lanterns, an example of which hangs at The Forgotten Souvenir. Innovative ideas such as crafting two sets of paintings — one of a background on paper and the other on mica to be placed over it — would create a multi-dimensional effect.

An exhibit from The Forgotten Souvenir

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

For example, if the set was of a nautch party, the background would be a veranda with a floating head. The mica painting to be placed on top of this, would have the body and head gear; it highlighted dimensionality as well as creativity, says Khushi.

At the exhibition is an example of a large mica work, a rarity as artists soon realised bigger works were not a profitable option. Executed by an artist named Sewak Ram of the Patna School, it depicts the Ramlila festival in Ayodhya. Sewak Ram was one of the pioneers in popularising “firkas” of standard sets of paintings.

Though these sets were created as depictions of daily life, such as a textile merchant with his wares or a tanpura player, their increasing popularity and demand, highlights the way India was viewed by the British — reduced to caste, class and community.

“This is a way the British documented India’s trades and professions and is one of the earliest examples of an ethnographic study. That is also why it is believed that the British created a class and caste system that was even more divisive than the one they came into,” says Khushi.

In South India, mica was mined in Cuddapah and deities were the hallmark of mica paintings from Tiruchi.

At the show

Running on a loop at the exhibition is a short film by Amit Datta titled Moments Before Mutiny. Using images from the collection Amit and the team put together a story about uneasy pace of life preceding the Revolt of 1857. The haunting score and the voice over add to the atmosphere of suspense.

An exhibit from The Forgotten Souvenir

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

“We have also developed an AR game alongside the exhibition, which gives visitors an in-depth look at the exhibition as they make decisions and choices, that reflect on their final outcome,” says Khushi.

A booklet that is a part of the exhibition contains the artistic, historical and academic facets of the exhibition as well as a commissioned essay by artist Rahee Punyashloka, who talks about mica in the contemporary context.

Mica paintings are specific to those 80 to 100 years in Indian history as it is no longer pursued today, and the exhibition is an interesting way of gaining insight into a society the once existed and the far reaching impact of colonialism as well.

The Forgotten Souvenir will be on display at the Museum of Art and Photography till February 23, 2025

Published – January 20, 2025 05:28 pm IST