Once wedded to Bollywood shindig, Anubhav Sinha, in recent years, has emerged as a gutsy chronicler of events that have threatened the idea of India. Finding his metier with Mulk, Anubhav went on to lend voice to the socio-politically deprived in Article 14, Anek and Bheed. Still remembered for the action-packed Sea Hawks on Doordarshan, this week, the seasoned director is diving into streaming waters with IC 814: The Kandahar Hijack.

Based on Captain Devi Sharan’s book, the six-episode-long Netflix series puts one of independent India’s biggest intelligence and security failures in perspective. In 1999, Anubhav says, he was in Mumbai, making music videos. “It was a phase of my life when I was busy making money and have no tragic memories of the period. But my director friends, Sudhir Mishra, Anurag Kashyap, and Hansal Mehta say I was politically aware at that time as well. Having grown up in Banaras and studied at Aligarh Muslim University, I had to be. In UP, siyasat (politics) is discussed at tea stalls and I frequented them often in both the cities.”

The six-episode series depicts personalities who are part of the security apparatus even today. Was he conscious? “I am not in the business of saving or glorifying people. Something happened, I did my research as authentically as possible, and here it is,” avers Anubhav.

Excerpts from an interview:

The IC 814 hijack is not exactly a success story; how have you approached the subject?

When I was approached, Netflix already had a script based on Captain Devi Sharan’s book on the incident. However, when I read it, I couldn’t agree to the project because the captain’s perspective was limited to what happened inside the aircraft. I wanted to know and tell more. So I rewrote it with screenwriter Trishant Srivastava who was part of the writing team before I joined. We approached passengers and officials and referred to news reports. Then (journalist) Adrean Levy came in with interesting insights from outside India.

We must understand that the hijack happened just months after big events like Pokharan II and the Kargil incursion. It was not easy for the government. Two hundred lives were at stake and it was a coalition government in the saddle. If you know about the times you will understand the film better, but if you don’t, you will still get a sense of the complexities involved.

What happened in Amritsar still touches a raw nerve. Were you conscious of the sensitive nature of the episode where the hijacked plane was allowed to take off?

Sensitivity, sarkari or otherwise, is like the audience — you can’t second guess it. One of the problems was that we were slow to react in Amritsar and it is something several bureaucrats from the time have publicly accepted. My thing is that one should not have malice in mind while telling the story. If the story is based on a truth, one should try to remain as truthful as possible. I have lifted all the curtains on the incident. You can put your camera wherever you like; you will only see the truth.

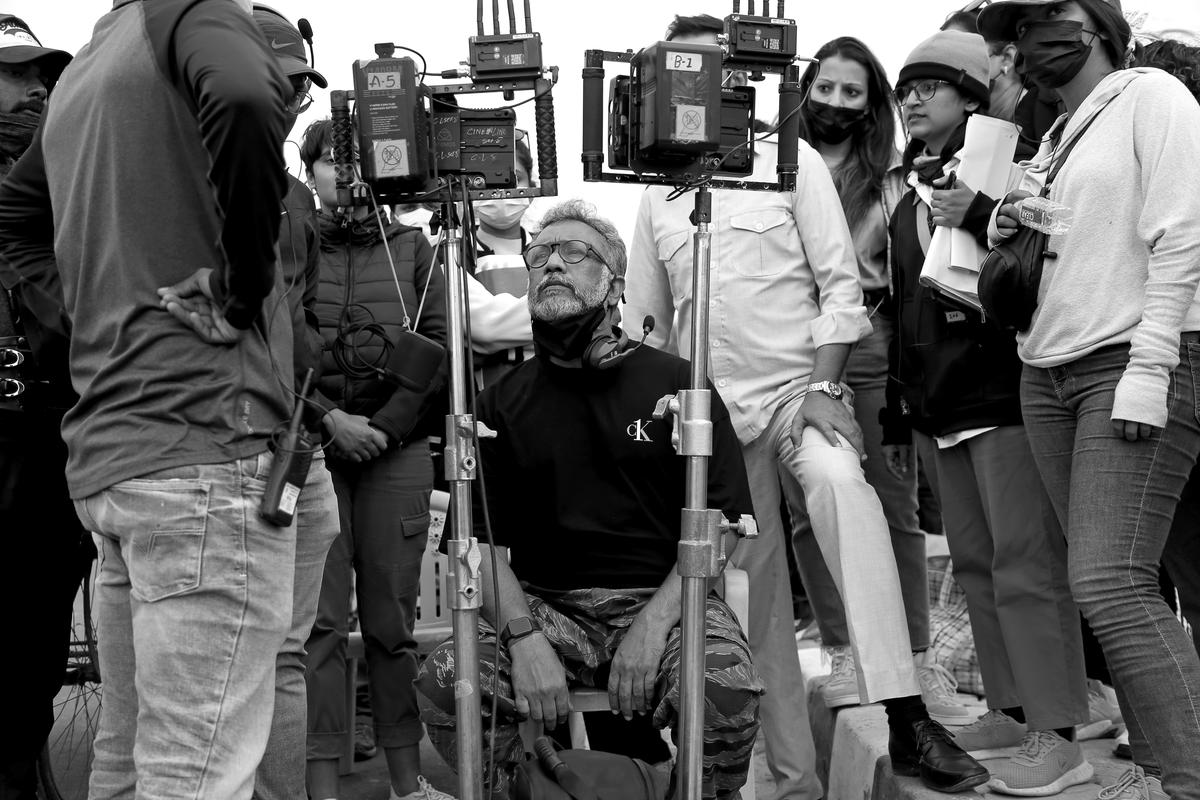

Anubhav Sinha on the sets of ‘IC 814: The Kandahar Hijack’

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

How do you get right the politics and the essence of the obscure language of bureaucracy in those rarefied rooms of the Secretariat?

I have never been inside those rooms. I don’t know many bureaucrats, but I enjoy baring them to their basic human instincts. The Crisis Management Group is full of personalities with different frequencies but they are working for a common goal. One is from a small village in Bihar and went to a government school, while the other is a son of a former IFS Officer who grew up in Europe. They look at the same problem differently. Their responses are different and it creates a fascinating mix.

During my research, I reached out to a bureaucrat who said he liked my work. He said he would not share any information but would love to meet me. I sat with him for three hours. After an hour or so I felt he was talking to me; I could see him sharing information in very thin layers but he never really said anything. It is surreal to explain, but I got something important from him.

How was the experience of directing so many actors of high calibre under one roof?

It wasn’t like we were aiming to make a Jaani Dushman! The story has many important characters. Arvind (Swamy) was among the first ones to come on board; he said he wanted to work with me. When I write a script, somehow a character starts behaving like Manoj Pahwa and another one starts acting up like Kumud Mishra. Even if I try to stop them, they slip out of my hands.

Then two bigger characters emerged. So, I approached Naseer (Naseeruddin Shah) bhai and Pankaj (Kapoor) bhai. Naseer bhai agreed without listening to the script, but surprisingly, Pankaj bhai, with whom I have had a relationship since Dus, took time. He said he didn’t want to be part of the crowd and read the entire script before saying yes. Out of nine actors in the room, six wanted to rehearse, and three worked on instinct. This arrangement is curious but fortunately, they give me a lot of love. When I said we would go for the take, even the one who wanted one more rehearsal, agreed.

Pankaj Kapur, Arvind Swamy, and Manoj Pahwa in ‘IC 814: The Kandahar Hijack’

| Photo Credit:

Neeraj Priyadarshi / Netflix

Whose performance surprised you the most?

The VFX team. The beauty of good special effects is that you don’t notice it. In Ra. One, we had a lot of time and money on our hands; here we worked with vendors to recreate the period. Except for Iran — which is facing sanctions — the aircraft, A300, is not in service anymore. Then getting the colour grading of Kandhar right took time. Historically and politically, it is perhaps the most significant city of Afghanistan but very little is known about it in recent times.

Is the pace of the series also guided by the period?

Before the shoot, my DOP Ewan Mulligan asked whether we were recreating 1999. I told him we were sending our camera and crew there. It is being revisited through today’s technology and is not a dated recreation of the event.

Having seen both the satellite and OTT phases, how do you see the churn in the entertainment space where data analytics is driving decisions?

The problem begins when you start interpreting success in terms of data. Art is an act of rebellion. The story of two brothers taking different paths had been told several times before, but Salim-Javed’s Deewar still became a game changer. Gandhi has been sketched millions of times but artists try to find newer ways to express his ideas. If you limit their vision by throwing some data, you are turning art into an FMCG product. You cannot process data unless you have enough of it. I don’t think analysts in the entertainment space have enough of it.

Anubhav Sinha

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

It seems something shifted in you when after ‘Tum Bin’ and ‘Ra. One,’ you suddenly started making socially-conscious and politically-aware films…

I was reacting to the situation but inadvertently ended up documenting the period. Having lived in Banaras and Aligarh during my formative years, I have a strange advantage. I love Girija Devi as well as Guns N’ Roses! The disturbance in the social fabric was troubling me and hence the voice came out. Thankfully it did. Now I don’t think I can ever make a film that doesn’t have a voice.

Will you stay the course despite their limited box-office returns?

I have made more money making small films than big ones, but now I am going through another churn. Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer blew my mind in the sense that a political film can also be spectacular. I connected with its form and felt if you want your films to have a voice, they need not be small.

IC 814: The Kandahar Hijack premieres on Netflix on August 29