Imagine an art gallery that spans an entire city, drawing millions of visitors in just a few days. This is the reality of Durga Puja in Kolkata, where faith, craft, and activism converge into a breathtaking public art spectacle.

I am in the city for a preview of the pandals as they are being assembled. It is a few days before heavy rains inundate the city, claim lives and flood many pandals. With themes ranging from food adulteration and acid attacks to Bengali literary thrillers, and titles such as Proshno (question), Artonad (scream), Nigurho (mystery) and Ocholayton (static), it isn’t surprising that newspaper headlines talk about the pandals this year being puzzles for the common man. Or an unofficial IQ test. But there are also thousands of religious pandals to view.

An idol of Durga at a pandal themed as Theyyam, a scared dance and worship ritual from north Kerala

| Photo Credit:

PTI

Workers deck up a pandal themed Free the birds from cages

| Photo Credit:

PTI

For the art visitor, however, it is fantastic. With intricate craft and impeccable concepts, and a scale that is rarely seen, the festival, widely described as the world’s largest public art festival, and recognised by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage, is comparable, if not better, than many international art festivals. To top it all off, many pandals are crowd funded.

Last year, I was disappointed that I could not take back any of the art I saw. I’d asked Sayantan Mitra from massArt, a non-profit that works to promote the art and culture of Bengal, if something could be done. This year, as we walk through new galleries set up at the Alipore Jail Museum for the preview, individual art works by the artists behind selected pandals are being sold.

Items for sale near a pandal

| Photo Credit:

PTI

A space for powerful narratives

Pujo, as it is known to many, was initially performed in the private homes of zamindars (hereditary landowners) across West Bengal. A confluence of factors transformed it into the cultural, social, and religious phenomenon that it is today, especially in the capital city. One was the philosophical influence of philosopher Swami Vivekananda and the Ramakrishna Mission, which elevated the festival’s spiritual and social significance. Also crucial was its role as a platform for political expression during the Indian freedom struggle.

Central myth of Pujo

The festival, a community-based activity in neighbourhoods and community spaces, is dedicated to the goddess Durga, an embodiment of the divine feminine power — also known as Shakti. The central myth behind Durga Puja is the epic battle between the goddess and the buffalo demon, Mahishasura. She is believed to have fought Mahishasura for nine days and nights, finally slaying him on the 10th day. This victory symbolises the eternal triumph of good over evil, virtue over arrogance, and knowledge over ignorance. And to honour it, pandals are erected across the city for nine days.

Mukho Mukhi pandal by artist Shovin Bhattacharjee fuses technology and tradition with stainless steel installations, kinetic energy-driven structures, and reflective elements

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The use of Durga Puja pandals as stages for social and political activism is a more recent phenomenon. Instead of merely decorating the pandal, community-based puja committees build artistic concepts around a central theme — encompassing the structure’s architecture, the idol’s design, the lighting, and even the surrounding environment.

In recent years, themes have moved from broad social issues to more pointed political statements. This is particularly visible in Kolkata, where major puja committees are often backed by rival political parties. Using the umbrella of the annual festival, which draws enormous patronage, artistic directors are pushing boundaries. They use it as a space for ideas, using craft and design to create powerful, piercing narratives on themes ranging from the environment and history to social justice and ideologies.

A pandal themed on ‘Operation Sindoor’

| Photo Credit:

PTI

Mirroring current debates

This year, one of the most interesting pavilions is non-profit organisation Tala Prottoy’s Beej Angan (seed courtyard). Spanning over 35,000 sq.ft., it tells a powerful story about agriculture, nature, and sustainability. The pandal shines a spotlight on issues such as food adulteration, rising prices, and the fallout of misguided farming policies. The Durga idol by artist Bhabatosh Sutar takes on the guise of a farm girl with a plough, slaying demons and farm policies.

At Tala Prottoy’s Beej Angan pandal, Goddess Durga as a farm girl holds a plough and stands on a urea bag in place of the demon.

| Photo Credit:

Sharan Apparao

An installation at Beej Angan

| Photo Credit:

Sharan Apparao

Another poignant pandal is one dedicated to the victimisation of women. Artist Anirban Das’ work is a graphic look at ‘burning’, a powerful metaphor encompassing torments such as rape, acid attack, human trafficking, domestic violence, and child marriage that women suffer in India. During the festival, survivors of acid attacks will join other women to perform short skits.

A performace at the Burning pandal, with artist Anirban Das’ work as backdrop

| Photo Credit:

Sharan Apparao

As I make my way through the city, I come across a pandal on the chaap, or stamp, in its metaphorical and literal form, suggesting the power of the image and its role in transformation; another designed as a giant illustrated strip, taking us on a trip back in time to the comic books of the 1950s and 60s, and the world of fictional detective Byomkesh Bakshi and Bengali literary thrillers; and even a quirky pandal titled Chaa that pays homage to the history of tea.

The Chaap pandal

| Photo Credit:

Sharan Apparao

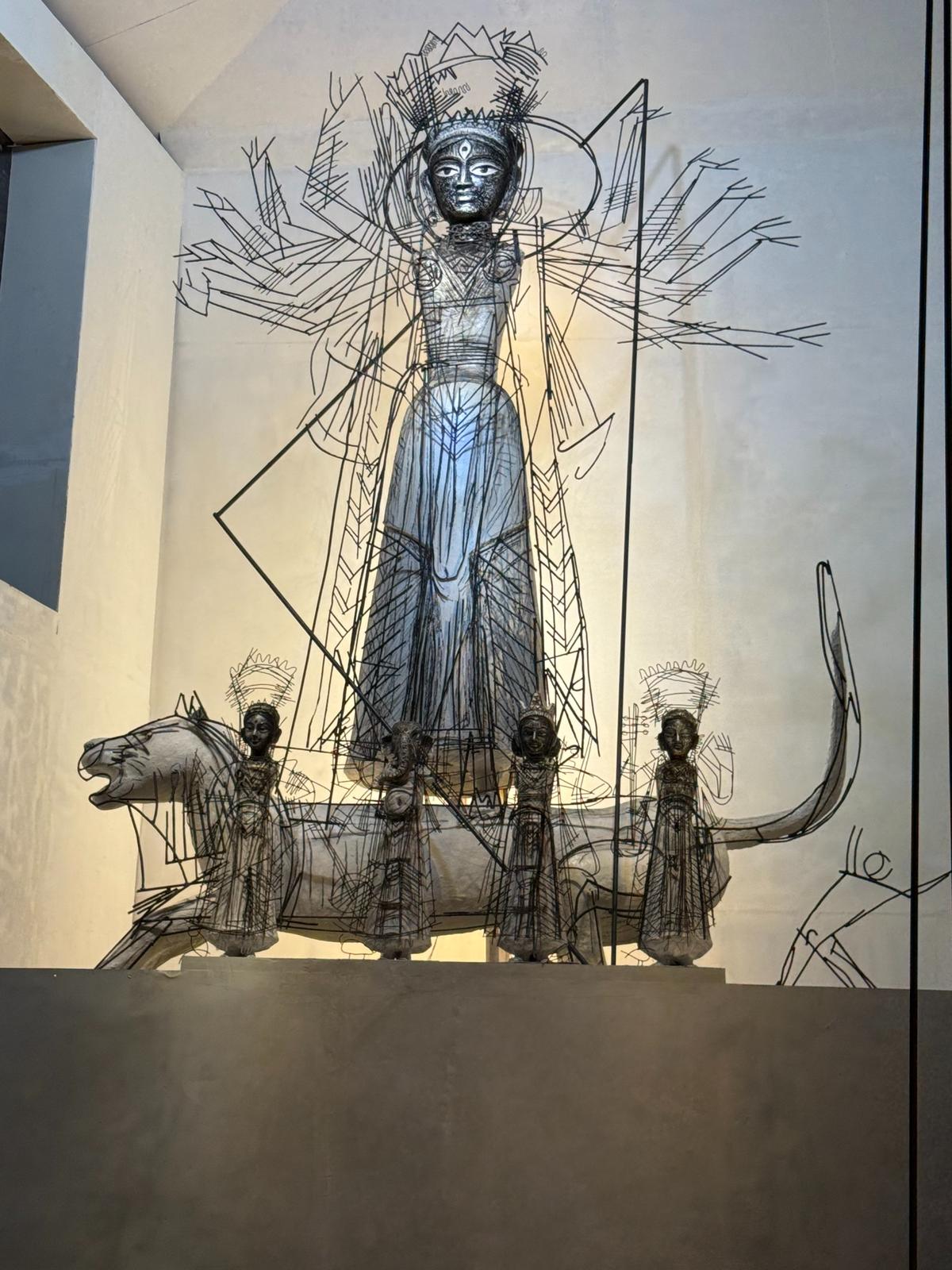

A metal Durga at Beliaghata 33 Palli’s Roti Kapda Makhan pandal

| Photo Credit:

Sharan Apparao

Raja Ravi Varma, the historically renowned artist who brought the human forms of gods and goddesses into homes with his chromolithographs, has a pavilion dedicated to his imagery. As does the powerful riots of 1946, which shook West Bengal. It is made visible in a dramatic combination of maps, oversized printing equipment, and newspapers of the event — handstitched for tactility and impact — suggesting the sociological impact on society in the history of change in India.

The pandal dedicated to Raja Ravi Varma

Igniting conversations

The pandals illustrate the power of art, taking the visitor through tableaus of powerful ideas. The common person, who may not be an art aficionado, is now being drawn into the fold with these visual extravaganzas.

Pakdondi, by Kashi Bose Lane Durga Puja Committee pandal, is a tribute to Bengali writer Leela Majumdar

| Photo Credit:

PTI

The world, and even the locals of the city, have yet to fully recognise this important change in the world’s largest public art festival. As these temporary installations continue to challenge conventions and ignite conversation, Durga Puja becomes not just a festival of faith but a profound agent of change.

40 painted taxis

Meanwhile, 40 yellow taxi cabs ply the city, decorated by artists, with motifs that draw on traditional pujas, Kolkata’s rock-band years, and even contemporary digital iconography.

Yellow cabs decorated by artists

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Asian Paints

A collab between Asian Paints and St+art India, the cars celebrate four decades of the paint brand’s Sharad Shamman award (for the best Pujopandal). Called “Cholte Cholte 40”, each cab is a moving time capsule, representing a decade of the awards.

Asian Paints x St+art India cabs

| Photo Credit:

PTI

The taxis’ interiors are upholstered in curtains, wallpapers and textiles from Asian Paints’ own collections, including fashion designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee’s Paris X Calcutta line for Nilaya by Asian Paints and the Heartland series. Under-seat lights, UV accents, and reflective finishes of Royale Glitz add to the pandal feel.

Interiors upholstered in Sabyasachi’s ‘Paris X Calcutta’ fabric

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Asian Paints

The writer is the founder of Apparao Galleries.