On April 12, 1950, while introducing the Representation of the People Bill in Parliament, the Minister of Law, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, emphasised that the preparation of an electoral roll is “a condition precedent for election”. The statutory framework in India, therefore, provides for periodic and special revisions to ensure accuracy of the electoral roll.

Nevertheless, there have been concerns about the decision of the Election Commission of India (ECI) to revise the electoral rolls in some States by carrying out a Special Intensive Revision (SIR). The question that arises is whether the ECI’s endeavour is ultimately directed at reinforcing or undermining public trust in the democratic process.

Restoring the foundation

There are two modes of updating rolls: intensive revisions, which rebuild the list from scratch, and summary revisions, which make incremental corrections. The last major intensive revision took place between 2002 to 2003. In recent decades, the ECI has relied on special summary revisions, under which claims and objections are invited on a draft roll. In the meantime, rapid migration, expanding urban centres, and high residential mobility have left electoral rolls riddled with duplicates, outdated entries and inaccuracies. Therefore, SIR 2025 was the need of the hour.

The implementation of SIR in Bihar in June 2025 resulted in the filing of several petitions before the Supreme Court labelling the revision exercise unconstitutional and illegal. The challenge proceeds on the basis that insistence on fresh enumeration and documents from existing registered electors is contrary to the constitutional right of universal adult franchise and will result in mass deletion of voters from the rolls. Notably, however, the authority to undertake such an exercise flows directly from the constitutional scheme itself, which vests the superintendence, direction, and control over the preparation of electoral rolls in the ECI. At the heart of this exercise lies the ECI’s endeavour to ensure that only eligible citizens vote, as envisaged under Article 326 of the Constitution. The revision and verification of electoral rolls is a routine and necessary process. Such corrections do not, by themselves, imply disenfranchisement or targeting. Countries such as Germany and Canada rely on civil registries or information sharing between different government agencies to update voter rolls; India does not have such a mechanism. The ECI must therefore independently verify eligibility.

The criticism levelled at SIR 2025 ignores the inherent difficulties in screening citizenship, which is the fundamental basis for eligibility to vote. These difficulties in ascertaining eligibility were, however, anticipated by the Indian legislature, which conferred power on the ECI to carry out a special revision in such manner as it may think fit. SIR 2025 is being carried out pursuant to the constitutional mandate and to ensure that no eligible citizen is excluded from the roll, while simultaneously excluding ineligible persons.

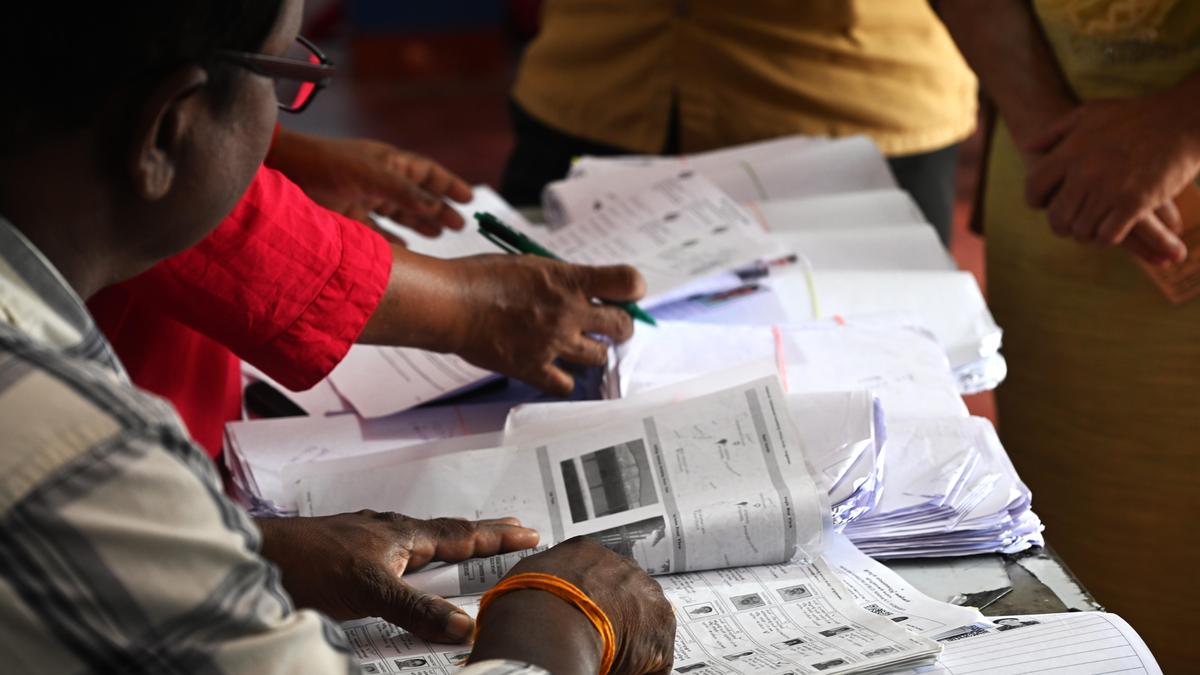

The detailed guidelines for SIR 2025 issued by the ECI contain administrative innovations, technological improvements, and efforts at transparency and participation. Under the present framework of SIR, the ECI has undertaken door-to-door physical verification of each elector. The onus of proving citizenship continues to lie on the applicant. However, the list of acceptable documentary proof is expanded to 11 items, from merely four in 2003, resulting in a more liberal and elector-friendly framework. At the suggestion of the Supreme Court, the ECI also agreed to accept Aadhaar cards as proof of identity. Further, booth-level officers actively assisted electors in tracing their eligibility and obtaining prescribed eligibility documents.

The SIR process marks a notable shift towards technological accessibility. For the first time, all supporting documents are digitised. Further, enumeration forms are being made available through online platforms. After the publication of the draft roll, any person who has any claim or objections has the option to file the same using the online platform.

The ECI did not restrict capacity-building to its own machinery but also trained booth-level agents of recognised political parties. The SIR guidelines also contain provisions for engagement with parties and sharing of electoral rolls.

What the numbers show

Over 7.5 crore entries were subjected to verification during SIR in Bihar. The total number of electors removed from the draft list was 65 lakh. In addition to the 1,60,813 BLAs of political parties, the Supreme Court also deputed volunteers from the State Legal Services Authority to assist in the submission of claims/objections/corrections online. Nevertheless, only 2,53,524 claims and objections were received in total after publication of the draft roll. Of these, only 36,500 were claims for inclusion (0.56% when compared to the total number of deletions during the revision). Not a single appeal was filed against any deletion. These figures indicate that the SIR exercise was, more or less, grounded in careful and accountable scrutiny.

By embracing SIR, the ECI has demonstrated that its constitutional duties will not be subordinated to convenience or political pressures. Instead, they are being pursued with clarity, courage, and accountability. A democracy strengthens itself not by avoiding difficult tasks, but by undertaking them when it matters most. SIR 2025 is one such effort.

Naira Jejeebhoy, Advocate whose area of practice includes election law and has represented the Election Commission of India in proceedings; Kumar Utsav, Advocate whose area of practice includes election law and has represented the Election Commission of India in proceedings

Published – December 10, 2025 01:24 am IST