During the course of my life, I have watched Phuphee work through countless cases and offer each one a tailored solution. But there was one that remained unsolvable. The case involved two sisters who had a feud that had been ongoing for 25 years.

My earliest memory of them is from when I was 14 or 15. It had been a hot, humid day and I had been too lazy to follow Phuphee into her room when they had arrived. That was the only time I saw them together. After that, it was always one or the other at the house.

Over the years their feud intensified, at times causing everyone in the village to go into a tizzy and talk of nothing else and, at other times, they were as silent as the graveyard. The villagers would sometimes talk about how the feud had started, but no one ever really knew what it was that had set the two at each other’s throats.

With time, it wasn’t just the sisters who were fighting but their families. As each sister’s family had expanded, so had the boundary of the feud. And once their immediate family members were in the fight club, the conflict slowly made its way into the village. The strange malady caused the people to express allegiance to one sister or the other even though it was never explicitly demanded by anyone.

The villagers sometimes found themselves getting into arguments and heated debates with their friends about the siblings. By the time the person would recover their senses, the damage had been done. Sometimes people speculated that the sisters were cursed and kept their distance, but then the enticing aroma of gossip would tickle their noses and draw them in and the cycle would start all over again.

One day in late September, my parents planned to drop me off at Phuphee’s house for a couple of days. The air was infused with a chill, causing you to pull your pashmina a little tighter around your body. We were sitting in the tonga enroute to the house when I saw a small crowd gathered by the side of the road, with some people shouting and abusing each other. The tongawaalla told us not to worry as they were probably fighting about the sisters. Once we reached Phuphee’s house, I ran inside to find her in the kitchen cleaning nadru (lotus stem). She got up and held me tight, and covered my face in kisses. She asked us to sit while she prepared nadru yakhni (lotus stem cooked in a yogurt and mint sauce) for lunch.

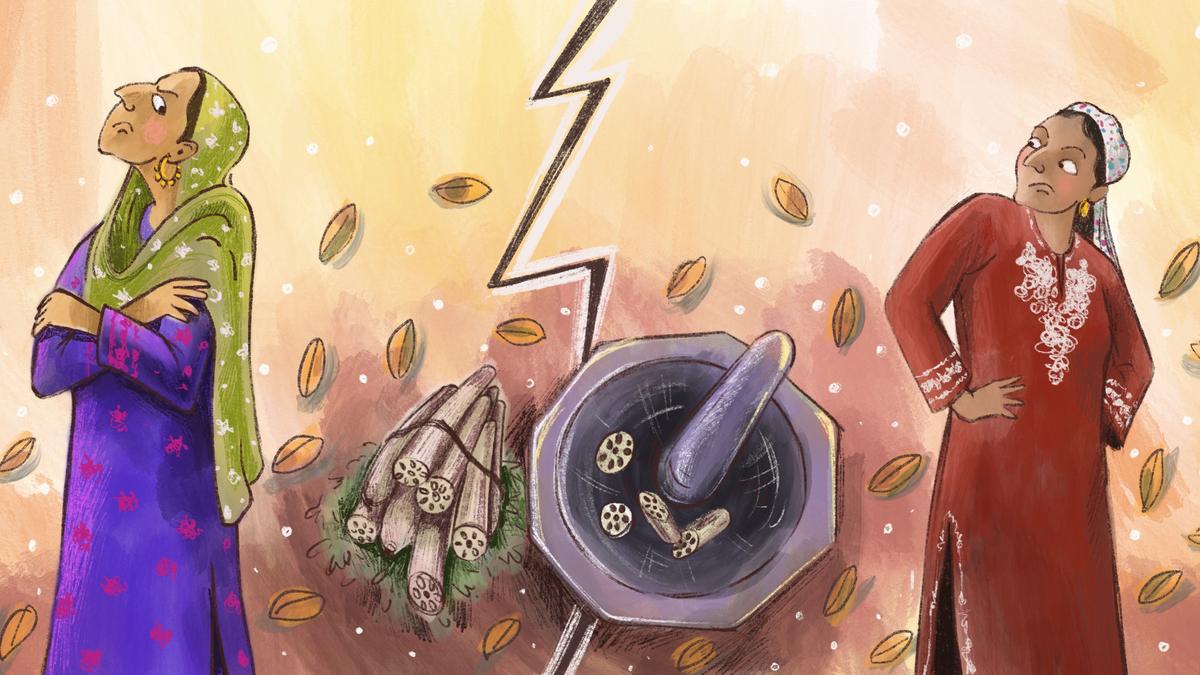

Later on, I was sitting with Phuphee as she pounded some nadru — the ones that were too hard to be cooked in the yakhni but would make excellent nadir monjyi (lotus stem cutlets). She would pound them into a coarse mixture, add egg and spices, and fry them in oil.

‘Sometimes no matter how much you steam these they won’t soften,’ she said, looking up from the giant stone mortar, a little flushed. ‘You have to pound them into submission.’

‘Phuphee,’ I asked, ‘what was the reason for the two sisters fighting?’

She stopped what she was doing and asked one of my cousins to take over.

She came and sat down beside me, lit two cigarettes and after smoking for a couple of minutes, told me the cause. The elder sister, Latifa, had been married for a few years and had two children when the youngest, Moomina, got married. After a year of marriage, Moomina conceived but had a miscarriage. Obviously distraught from the trauma, she had gone to her maternal home to recover. It had been very difficult for her because there had been a lot of pressure on her to conceive.

When at her home, she opened her heart to her sister who had tried to console her. Latifa had said that it probably wasn’t a bad thing given that Moomina had just started a new job as a teacher and having a baby would have put hurdles in her path. Upon hearing this, Moomina had become disturbed and asked her sister if she viewed her own children as hurdles to her career. One thing led to another and 20 years later the feud continued. I was stunned.

‘I always expected it to be something big that they had fought about,’ I said.

‘Big or small, that depends on whether you are Moomina or Latifa, of course. Latifa has refused to acknowledge or apologise for what she said, citing seniority as her reason,’ Phuphee replied a little sharply.

I understood the change in her tone. It is possible it might have been a slip of the tongue for Latifa, but for Moomina it was an act of cruelty that would stay with her.

I asked Phuphee why she hadn’t used her magic to help bring them together.

‘I wish people were like nadrus,’ she said. ‘If they didn’t become tender on cooking, you could still pound them into submission in the nyaem [mortar]. But they are not. There is no forgiveness without acceptance of your sin. Latifa might feel that what she said wasn’t terrible, but the thing to remember about a situation like this is that the person who delivered the blow doesn’t get to decide how painful or how deeply it cut the person who received it. When you hurt someone, you don’t get to decide how much pain the other person should feel. You don’t have the right or the power.’

I sat there thinking about her words and the two sisters. I wished there was some way to bring them together, but Phuphee was right. You couldn’t pound sense into anyone, especially someone who held their sense of entitlement on a higher plane than everything else.

Saba Mahjoor, a Kashmiri living in England, spends her scant free time contemplating life’s vagaries.

Published – September 26, 2025 07:07 am IST