On July 20, 2017, Harmanpreet Kaur played what was, arguably, the most important innings by an Indian woman cricketer. Her audacious 171 runs off 115 balls against heavyweights Australia in the semi-final of the ICC Women’s ODI World Cup became the knock that made Indian audiences begin to see “women’s cricket” as what it truly is: cricket.

Almost 5,000 miles away from Derby, England, where Kaur was dismantling the defending champions’ bowling attack, 15-year-old Uma Chetry found her purpose. In her local club in Assam’s Golaghat district, Chetry got goosebumps just hearing the score. Between juggling school, farming duties with her parents, and cricket practice, she would watch the highlights on repeat. She declared to her teammates, “One day, I want to bat like that. One day, I want to play with Harmanpreet Kaur.” Seven years later, on July 7, 2024, Chetry became the first woman cricketer from the Northeast to make her India debut. The blue cap was handed to her by captain Kaur herself.

Uma Chetry during a T20 match between India and West Indies in Navi Mumbai, December 2024.

| Photo Credit:

Emmanual Yogini

Like Chetry, Kranti Goud’s story too is about raw talent bursting through in cricket’s less celebrated geographies. Back in 2017, in Ghuwara village near Khajuraho in Madhya Pradesh, 14-year-old Goud was leading her district team to the final of a U-19 tournament. Local coach Rajiv Bilthare was struck by her “speed that can only be God’s gift”. That spark matured into an impressive spell, with six wickets in just her fourth international match, handing India a rare ‘away’ series win against England this July.

India’s Kranti Goud in action during an ODI match between India and Australia in New Chandigarh on September 17, 2025.

| Photo Credit:

PTI

Cricket was far from an option for N. Shree Charani from Andhra Pradesh’s Kadapa district, best known for its temples and karam dosa. According to her father Chandrasekhar Reddy, a junior worker at a thermal power plant, cricket being a team sport, his daughter, good at athletics, kho kho, volleyball, would not get “noticed”. Except, destiny had other plans for the teenager who just wanted to “play, play, play”.

At this year’s Women’s Premier League (WPL), Shree Charani, 21, took four wickets in just two games for the Delhi Capitals. That was enough for India coach Amol Muzumdar to hail her as the “find of the tournament”. Within months, she was fast-tracked into international cricket. With 10 wickets in India’s T20 series win over England — where she was named Player of the Series — it will be safe to say Shree Charani’s father had to eat his words, and happily so.

Bowler N. Shree Charani during an India vs. Australia ODI match in New Chandigarh, September 14, 2025.

| Photo Credit:

SHIV KUMAR PUSHPAKAR

Chetry, Goud and Shree Charani are more than just newcomers in India colours; they carry small-town dreams to the grandest stage of them all — the ICC Women’s ODI World Cup, which kicks off on September 30. More than half of India’s 15-member squad will be making their World Cup debut. They are signposts of a larger cultural shift: cricket breaking out of its metropolitan mould even further, families and communities recalibrating their ideas of what their daughters are capable of, and young women from India’s Tier 2 and 3 towns dreaming big.

India captain Harmanpreet Kaur (right) with Kranti Goud after their win in the Metro Bank One Day Series between England and India, July 2025.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Many firsts

• Indian women are eyeing their first-ever World Cup trophy (only the U19 girls have won twice, not the senior team).

• Australia are the defending champions and the most successful team in ODI World Cups — with a record seven wins.

• Apart from Australia, only England (4) and New Zealand (1) have won the World Cup.

• India (Guwahati, Indore, Vizag, Navi Mumbai) are the hosts, but Sri Lanka (Colombo) too is one of the venues as Pakistan cannot compete on Indian soil. (All Pakistan games will be played in Colombo.)

• This year, for the first time, there will be an all-woman match officials panel (14 umpires and 4 match referees).

Period of growth

No one understands this better than former India captain Jhulan Goswami, whose own journey from Chakdah to Kolkata in the late 90s — two hours each way by train just to get to a ground — is as legendary as her wickets tally. “We are a nation undergoing transformation, and today you will see women in arenas that were unseen and unheard of, say 10 years ago,” she says. “The population is young, and every girl wants to do something worthwhile with her life. Cricket is just another medium. The sport has always been popular, and invokes so much pride. Now, finally, it has started giving financial security to the girls.”

“The population is young, and every girl wants to do something worthwhile with her life. Cricket is just another medium. The sport has always been popular, and invokes so much pride. Now, finally, it has started giving financial security to the girls”Jhulan GoswamiFormer India captain

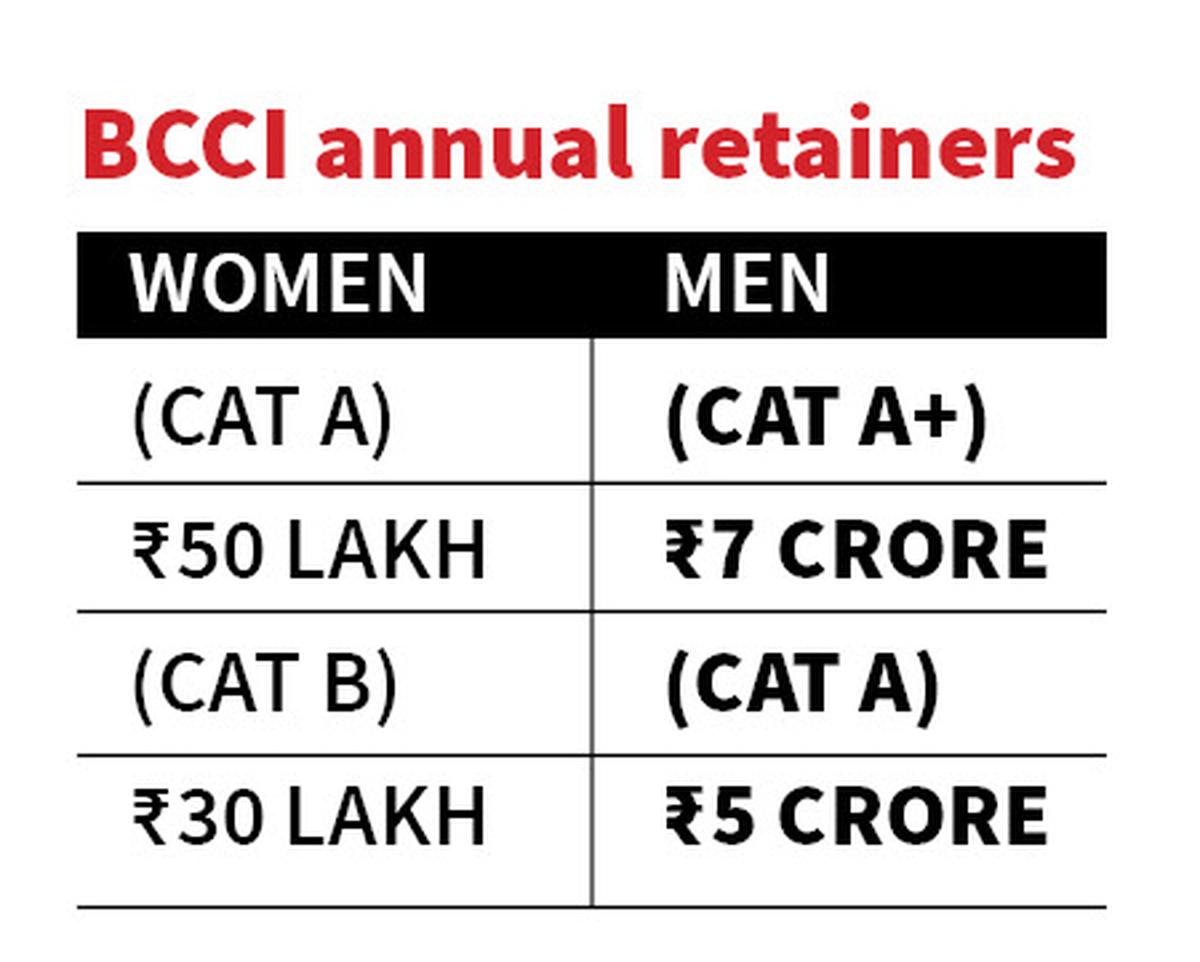

Goswami and her long-time teammate and partner-in-record- breaking, Mithali Raj, have lived through the full-circle of the story of women’s cricket in India. They started their careers before the women’s game came under the ambit of the Board of Cricket Control in India (BCCI), and the players were almost always broke. “We were emptying our family’s pockets to play for India,” recalls Raj, the highest run-scorer (across formats) in women’s international cricket. “We used to organise everything on our own, tour after tour, purely because of our passion for the game.”

When the Raj-led team returned from South Africa as World Cup runners-up in 2005, it was in anonymity, just like much of their careers had been until then. Days later, each player received a cheque for a paltry ₹9,000 from team sponsor Sahara. In sharp contrast, when the Indian men’s team returned as runners-up in 2003, they were handed plush apartments in Sahara’s Amby Valley in Pune, in addition to cheques from multiple sources.

Former India captain Mithali Raj during the ICC Women’s Cricket World Cup 2025 trophy unveiling event in Bengaluru, September 13, 2025.

| Photo Credit:

PTI

The 2017 World Cup, where all matches were televised live, and India finished runners-up, marks the clear dividing line between the ‘before’ and ‘after’ eras of Indian women’s cricket. The International Cricket Council’s digital and social media platforms garnered a record 100 million views, doubling the coverage that the women’s game was badly in need of. “Not once were we made to feel like we lost the final,” Raj says, of the time they returned from England.

Until then, she and Goswami had spent their lives bringing laurels to the nation, all in obscurity. “I had never been so busy and in so much demand ever in my life,” says Goswami, of the countless interviews, studio visits, events, shoots and public appearances in the months that followed. The next few years, capped by another runners-up finish in the 2020 T20 World Cup, were marked by unprecedented growth.

Breaking generational patterns

Royal Challengers Bengaluru captain Smriti Mandhana trains during the Women’s Premier League 2025.

| Photo Credit:

Murali Kumar K.

But it was really the WPL in 2023 that changed the grammar of opportunity for women’s cricket in India. Institutionally, it has been the most significant change, especially in a system where domestic players still wait for formal contracts. And for the first time, the women in blue were being valued. Batter Smriti Mandhana’s ₹3.4 crore deal with Royal Challengers Bengaluru made headlines, but the ripple effect was felt deeper, as even uncapped domestic players began earning life-changing sums in a single auction.

“After WPL, you can finally say, yes, cricket can be a profession,” says Raj. “Earlier, families saw cricket as a gamble, now they see it as a career.” In addition to WPL, almost all Indian states now have their own T20 leagues for women, which means more game time, more chances to get noticed by talent scouts, and of course, more money.

But salaries tell only half the story. Beyond finances, the league has given these women something less tangible but more powerful — confidence. They want to be seen, and heard. For the girls from smaller towns, the hurdles have always been bigger — long commutes, fewer facilities, increased social scrutiny. But playing in front of packed crowds in Tier 1 stadiums in Bengaluru, Mumbai and Delhi means the current generation doesn’t shrink under pressure, they flourish. Their approach to the game is fearless too, far from the nervy, risk-averse approach of their predecessors. “The league has prepared this current lot for international cricket,” says all-rounder Jemimah Rodrigues, part of the ODI World Cup squad. “They are ready to give it their all and are not afraid to express themselves. It doesn’t matter if they fail, but the spirit and energy is something else and that rubs off on the whole team.”

India’s Jemimah Rodrigues takes a victory selfie with her team after India won against England in the Women’s Metro Bank ODI series in England, July 2025.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

This confidence isn’t just a cricket story; it mirrors a larger shift in India. Of young women becoming engineers, pilots, police officers, army personnel, entrepreneurs — their visibility itself becoming a form of power. For all the records, contracts, and World Cup dreams, the meaning of this shift is perhaps best understood in the quiet rewards at home, where mothers play a proactive role in breaking generational patterns.

Mother knows best

In Golaghat, Uma Chetry’s mother knows what sacrifice means. Married young, her own schooling was cut short, and life became a cycle of caring for and raising six children. Through it all, she stood firmly behind her only daughter’s seemingly improbable cricketing dream. Today, when Chetry returns home with a new sari for her mother, she sheds a quiet tear. Not just out of joy, but also pride that her daughter’s fate won’t be the same as hers.

In Kadapa, Shree Charani’s mother has only one thing to tell her daughter: “Chinna, you do whatever you want to, I am with you.” That unflinching faith has found its reward. When Shree Charani came back from the England tour in July, she gifted her mother with a gold ring — a reminder that her faith was never misplaced.

India’s N. Shree Charani at a practice session in Mohali, September 12, 2025.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

For Kranti Goud’s family, the sacrifices were perhaps greater. After the bowler’s father lost his job as a police constable, her mother sold her jewellery so their daughter could keep playing. This July, after Goud’s heroics in England, her village celebrated by putting up congratulatory posters in her name. One day, some strangers followed these posters all the way to her home; finding Goud away, they posed instead with her mother who now basks in the glow of her daughter’s fame.

For these mothers, the pride is personal. But for the country, the meaning is larger. Daughters are no longer exceptions; they are role models. And as India heads into a home World Cup, these stories from the smaller towns and villages remind us that women’s cricket is not just a sporting movement. It is part of a deeper social transformation, of families rewriting what is possible for their daughters. And of India itself slowly, but surely, keeping pace with their dreams and ambitions.

Dreams that once ended in dusty village grounds now stretch to the world’s best stadiums and biggest competitions. And in that arc lies the story of a changing India — where young women no longer wait for permission to dream, but claim the spotlight as their own.

The writer is an independent sports media professional and author of the award-winning book Free Hit: The Story of Women’s Cricket in India.