For representative purposes.

| Photo Credit: Getty Images

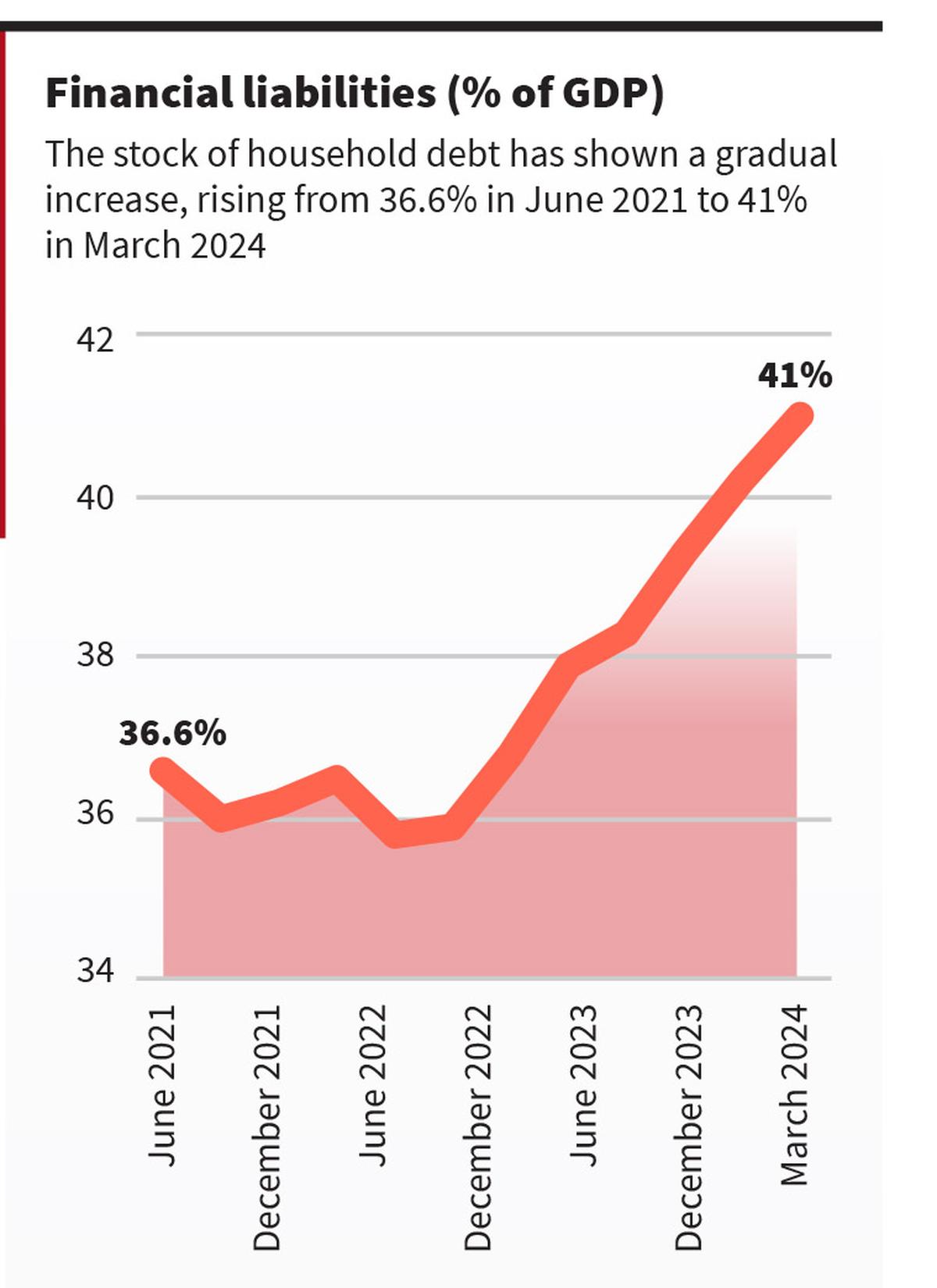

The release of the Financial Stability Report (FSR) 2024 by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has called attention to the question of household finances and consumption loans. The stock of household debt has shown a gradual increase, rising from 36.6% of GDP in June 2021 to 41% in March 2024. According to the FSR, it has risen to 42.9% in June 2024. Even though household debt in India is lesser than most emerging market economies, the rise in household debt-to-GDP ratio is of concern.

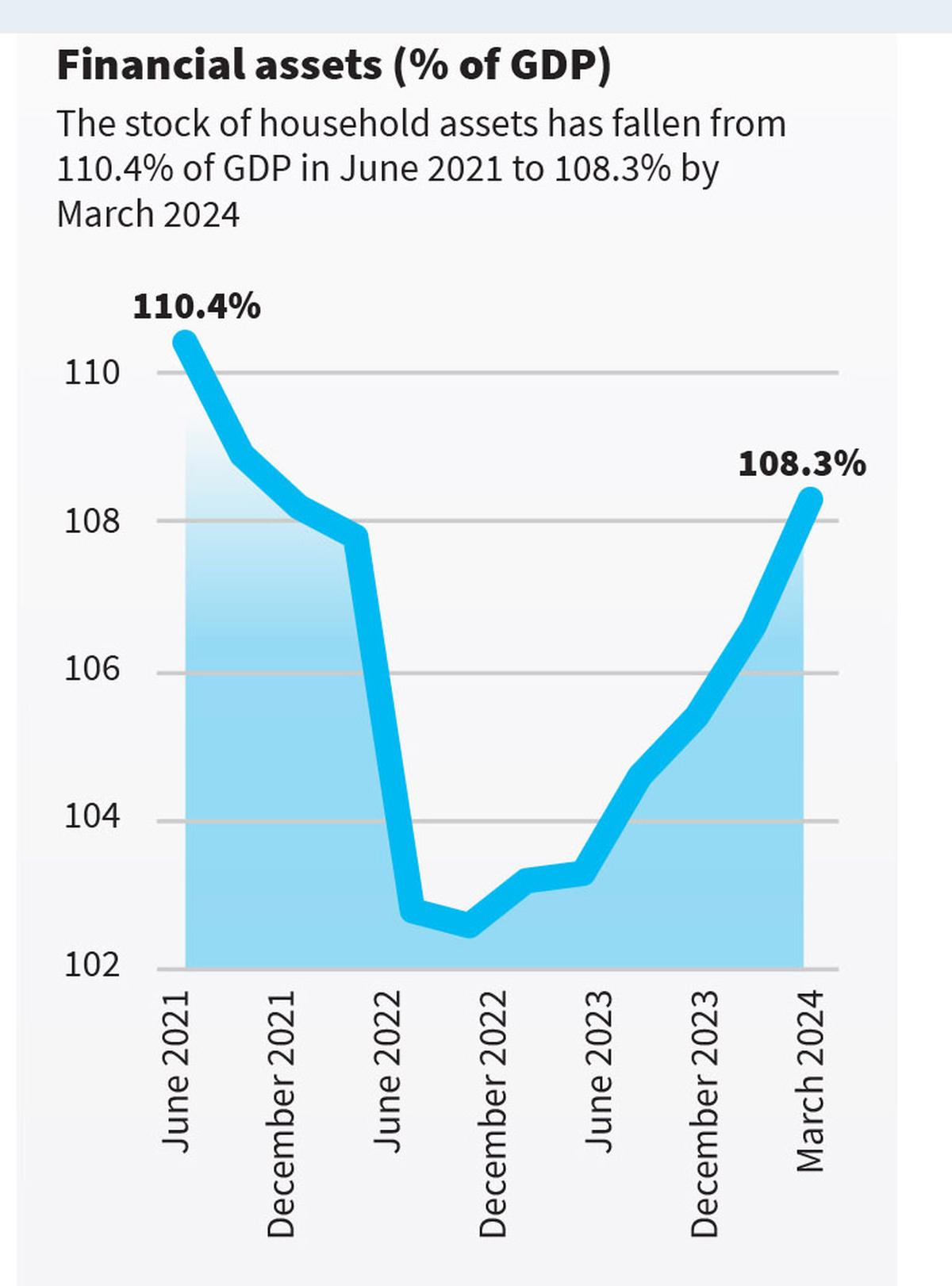

Debt is largely taken to build up holdings of assets. However, the stock of household assets has fallen from 110.4% of GDP in June 2021 to 108.3% by March 2024. A reduction in assets and an increase in debt indicates that a greater proportion of borrowing is being used for consumption. Even though the RBI highlights the shift towards healthy and prime borrowers in the economy, the fact that there is a significant amount of borrowing being done for the purpose of consumption is a cause for concern, which might indicate macroeconomic weakness of the economy.

Healthy borrowing and borrowers?

Even though household debt has increased significantly, the RBI highlights several points pointing towards the health of the Indian economy. For one, the RBI presents data to indicate that rising borrowing is being driven by an increase in the number of borrowers rather than rising indebtedness. Secondly, the proportion of sub-prime borrowers has been reducing, with almost two-thirds of debt belonging to prime borrowers and those with above prime credit quality. Rising per-capita debt amounts is witnessed only for super-prime borrowers, indicating that only highly-rated borrowers are undertaking larger levels of debt, mainly using it for asset creation.

Borrowing by individual consumers has been an important source of credit growth since the pandemic. The RBI did introduce measures to curb this growth, leading to a slowdown in credit growth since September 2023. The slowdown has seen a shift towards healthier borrowers, with sub-prime borrowing seeing a relative reduction. This can be seen as a net positive outcome, indicating healthy credit growth focused on asset creation by worthy borrowers, and an increase in borrowing without an increase in average indebtedness.

On increasing consumption

However, there are some worries. The share of loans taken for consumption purposes has increased over time. Households are taking on credit largely for consumption purposes and not to accumulate assets such as houses or vehicles, or to invest in education. The increase in borrowings by prime and super-prime borrowers hide the fact that much of borrowing for consumption purposes is being done by households with lower levels of income.

While 64% of loans taken on by super-prime borrowers are for asset creation, nearly half of the loans taken on by sub-prime borrowers are for consumption purposes. Households earning less than five lakh have largely taken on unsecured loans, such as credit card debt, for consumption purposes while richer households largely take on debt for purposes of purchasing housing. Amongst forms of debt, personal and credit card debt have shown a gradual increase in delinquencies in September 2024 relative to September 2023, indicating greater stress for lower-income households. The RBI outlines the dangers emanating from financial stress for lower-income households. Around half of all borrowers with credit card debt or personal loans also have housing or vehicle loans. A default in any category leads to all loans of the same borrower being classified as non-performing loans for the lending institution. Thus, if a borrower defaults on credit card debt or a personal loan, the housing loan will also be classified as a non-performing asset. Rising stresses in unsecured loans can spell weaknesses for higher-value loans as well. The RBI is keen to assert that the loan make-up is gradually shifting towards more prime borrowers, with sub-prime borrowers reducing. This may be the case, but the overhang of consumer debt implies that macroeconomic problems might arise.

The impact of debt on the multiplier

The rise in borrowing for consumption specifically among households with lower levels of income is something that requires due attention. What factors have driven this increase? Has it come about because households have faced greater income insecurity since the pandemic, and are hence borrowing through the medium of credit cards and unsecured loans to tide over income and consumption shortfalls? Or is it because financial innovations have allowed for households to undertake larger borrowings on the back of financial instruments like credit cards? The former indicates a weak macroeconomy, while the latter carries with it uncomfortable questions, such as the role of financial innovation in leading to the development of fragility and stress by exposing lower-income households to greater debt, pushing them towards financial marginalisation.

Regardless of the factors leading to an increase in this category of loans, the fact that the share of consumption loans has been rising is not a healthy outcome, as it indicates a relative reduction in the number of assets being created even as households become more indebted. Increasing household debt — especially for poorer households — implies a reduction in the power of the income multiplier. The multiplier, which indicates how much output increases for a given increase in investment, is greater for lower-income households, since a greater proportion of their incomes is translated into consumption of goods. Richer households will have a smaller multiplier, since most of their immediate needs are met, and a greater proportion of their income goes into savings.

However, if lower-income households are saddled with debt, some proportion of their income will go into servicing their debt, leading to lesser spending and hence a lower multiplier. An economy with greater levels of household debt, especially from poorer households, might show lower growth for the same amount of investment. In this case, it remains to be seen how much impact macroeconomic policy moves such as the reduction in income-tax rates would have, if households are largely indebted. There might be certain indications that the borrowing structure is healthy and shifting towards super-prime borrowers, but policy will have to remain awake to the possible sources of fragility engendered by the increase in consumption loans and the proliferation of unsecured forms of consumer credit.

Rahul Menon is Associate Professor in the Jindal School of Government and Public Policy at O.P. Jindal Global University.

Published – March 12, 2025 08:30 am IST